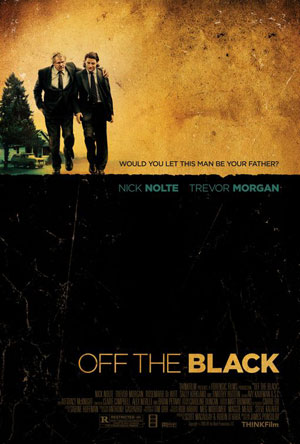

In Off the Black, Nick Nolte plays a grizzled old ump who makes a controversial call on a high school student ballplayer. Later that night his house gets vandalized by a group of guys – he manages to catch one and march him inside at gunpoint. The vandal? The ballplayer, of course. Nolte offers him the opportunity to make amends – repair the damage and he won’t call the cops. Over time, a friendship develops between the two, leading up to Nolte asking the boy to come to his high school reunion… and pretend to be his son.

In Off the Black, Nick Nolte plays a grizzled old ump who makes a controversial call on a high school student ballplayer. Later that night his house gets vandalized by a group of guys – he manages to catch one and march him inside at gunpoint. The vandal? The ballplayer, of course. Nolte offers him the opportunity to make amends – repair the damage and he won’t call the cops. Over time, a friendship develops between the two, leading up to Nolte asking the boy to come to his high school reunion… and pretend to be his son.

Writer/director James Ponsoldt makes his feature debut with Off the Black, and he gave me a couple of minutes of his time on the phone last week. I thought it would be an excellent opportunity to get inside the mind of someone who has just broken through, and to see what kind of advice he could offer to the aspiring filmmakers reading this site.

There’s something interesting in the pairing of the old, washed up sports guy with the young, up and coming sports guy. It seems like sports is an area where you really have just one shot before you’re suddenly too old or physically used up. Can you talk about that in terms of creating the Nick Nolte character?

I think we live in a society that fetishizes youth now more than ever before. In sports we ??? a man’s career by the years they have and these very specific statistics. I think there’s definitely the question of what does an old athlete do; what’s their second career. Especially with an umpire in this case – what’s going on behind the mask. I think someone like Nick Nolte, who has very much grown up in front of the camera – he’s been a star since Rich Man, Poor Man, which was 35 years ago. There’s been all these phases of his life, which you can pretty much mark by all the films he’s been in. I think having him in a film with a younger character who has an essential softness about him – Trevor Morgan’s Dave – offers more of a counterpoint between the two of them. What’s great about Nick Nolte, in his face alone, is that his face is a map of his life. You can tell that he’s lived, and he hasn’t censored himself in any way. He’s lived very hard and isn’t ashamed of it. I’m drawn to characters like that.

It’s interesting you say that – Nick Nolte has lived very hard, and he’s become a bit infamous for it. When you’re making your first feature film and you have Nick Nolte playing one of your leads, do you ever get worried about controlling him on set?

Before I ever met him, I was terrified of him. For so many reasons. He has a public persona, but like so many times when you meet the person you realize the public persona doesn’t have any correlation to who they really are.

My producers, Scott Macauley and Robin O’Hara, co-produced some French films by Olivier Assayas, including this movie Clean, which starred Nick Nolte and Maggie Cheung. They were the ones who suggested Nick, and I loved the idea, but again I was scared. I said, ‘Is he going to attack people on set? Is he going to be sober on set?’ I knew what everybody who had seen that awful mugshot on the internet knows. The first thing they told me was, ‘No, no, he’s a wonderful, gentle man. If he commits to doing your movie – which there’s no guarantee, because he’s very picky and there are a lot of other great actors out there who can’t seem to stop working but Nick’s not one of them – but if he commits to your movie he’ll be a complete pro.’ He was. He’s great. On set he’s like a child… with that wonderful face and voice. He’s like a child in that he’s like an 8-year old who wants to play. He works pretty egolessly, he treats everyone on set with respect, he likes being given direction.

A good example is a scene where he sits down and a beer explodes in his face and he starts laughing. That happened more or less because of an accident. We did one take and the beer had been shaken up accidentally and it exploded. You’re left with Nick Nolte with beer dripping from his face, which in some ways is funny. I told the propman to shake up every single beer. Then I went to Nick and I said, ‘That beer is lifeblood to you. It’s gold, you can’t waste a drop of it.’ I looked in his eyes and you could see these wheels turning. He loves finding what’s spontaneous and natural in things. Nick’s not afraid to be ugly in service of the truth.

A lot of my readers are aspiring filmmakers. Can you talk about the arc that takes you from wanting to make films to having Nick Nolte star in your debut?

I went to film school at Columbia in New York. I made a number of short films, and none of them seemed all that commercial and weren’t conceived as things that would be perceived as ‘calling card’ short films. One was about a family dealing with oxycontin addiction in Kentucky. The next one was about a mother that kidnaps her daughter and were on the run. They weren’t commercial, but they were the types of things that I cared about and I would like to have seen.

I was lucky in that both played in a number of festivals around the world and I was able to go to some of those festivals. While at the festivals I met a lot of people – a lot of other filmmakers, obviously, which is great, because you feel like you have a peer group and you’re keeping up with friends who are making film and you’re learning from them. And you meet producers and agents and managers and people who say they want to help you because they liked your short, and they perhaps can. You meet a lot of people who say they want to help you and they’re pathological liars, perhaps, and they have no relationship with the film industry. You meet them too.

I think making a short film is the best training one can have for making a feature. Making a short film, I found, is really exactly like making a feature except a tenth of the process, timewise. By my last short we had a pretty big crew, and it was the same stakes – I had to storyboard the film, and I had to plan it out as if I was making a feature. After the shorts I had a feature script and just started doing tons and tons of meetings. I was lucky enough to have an agent at that point who could set up meetings with people who read the script and liked it.

I wrote this script and I knew I was going to make this film. I set a date for myself, that I would make it by this date, and I decided I wouldn’t make it cost-prohibitive so that if I had to make it for $25,000 on digital video with theater actors I would. I was just going to make this damn movie, because it’s a two person film and there’s nothing in the script that’s cost-prohibitive. That being said, when you take it to the production companies of the world, when they see a small, character driven script like that, there’s a phrase they use, which is, ‘This is execution dependent.’ Which is to say it’s not a sequel, it doesn’t involve superheroes, there’s no franchise there. If you pull it off, if everything comes together, if you get the right casting, it’s potentially something they could make money off of.

Also I was unproven, I had never directed a feature. What it took was people who were more established in the industry and had name recognition signing on and agreeing to do the film. I would say Avy Kaufman, my casting director, carries a lot of weight in the industry. Last year she cast Capote, Brokeback Mountain, Syriana. She’s just all over, and when she signed on she legitimized it. When Scott Macauley and Robin O’Hara signed on it legitimized it within the independent film world. When Tim Orr agreed to be my cinematographer, anyone who follows the films David Gordon Green has respect for Tim. It became a much more legitimate film.

It got done with fits and starts and with people who were older and more experienced taking a shot on believing in me.