A.D.D (Vertigo, $24.99)

by Graig Kent

I’m not a gamer, at least not in the sense as it’s colloquially known today. I don’t fanatically play video games, and beyond my iPod Touch I don’t actually own a gaming system. I’m prone to killing time with Angry Birds or Plants vs. Zombies or some Flash game on-line from time-to-time but I have next to no investment in an X-Box or Wii or any MMORPGs. I’ll even admit that I’m more likely to enjoy watching someone play a game than playing it myself. It’s just not in my blood. Not that I have anything against gaming, I just have a greater interest in “analog” (read: board or tabletop) games, playing them with my kids or holding games nights with friends (actual socialization versus virtual interaction). But I digress.

The story behind the new Vertigo original graphic novel, A.D.D.: Adolescent Demo Division, is derived from the idea that gaming and gaming culture — and to a further extent, media and branding — are dominating factors in shaping and influencing youth culture today, and presents a theoretical extreme that it could reach, both in inspiring and controlling children.

The plot revolves around a group of teenagers, the stars of the hit reality show “A.D.D.”, the world’s preeminent gamers, idols of millions, wards of the Nextgen corporation, and their main cash cow. Behind the scenes of A.D.D. looks like a private school of sorts, only where the pupils are encouraged to game as much as they can, and think as little as possible, while occasionally being subjected to a battery of tests. These kids have grown up in A.D.D., having been adopted and raised by the company, and hovering before them is “graduation”, based on their performance, freedom to the “realworld” and the promise of meeting their birth mother.

Of course, nothing is really as it seems, especially since some of the kids have started developing new skills. Takai can take apart and fix anything with blazing speed. Kasinda can see the intentions of “realworlders” with a glance. Karl is preternaturally gifted at gaming, especially killing. And Lionel, well, Lionel can see through technology and advertising and see the real meaning, or perhaps it’s prognosticate its impact. As the kids become more aware of themselves and their surroundings, suddenly they see the only home they know as a threat, but despite (or perhaps because of) all that gaming they have developed neither the skills nor wherewithal to oppose their superiors or defend themselves.

Though I had no expectations from the book, an original graphic novel from Vertigo, especially one released in hardcover, usually has a certain level of quality attached to it by default, and in that respect A.D.D. is a let down. Written by noted cyberculture and media theorist Douglas Rushkoff, A.D.D. swings hard on a conceptual level but whiffs on the entertainment side. Flat out, the book is both derivative and dull, with components of the book reminiscent of dozens of stories from multiple media like Ender’s Game, Solarbabies, Suspiria, Dollhouse, Gamer, Morning Glories and countless others.

The story Rushkoff surrounds his media and cultural critiques is, sadly, uninteresting. There’s little shock or wow, there’s little that is unexpected, and most of all, very little investment in the characters, which is especially damning when the story is so familiar. They’re not complete voids or basic archetypes, but at the same time their relationships with each other are so overly simplified that they never feel more like anything but characters following a plot.

While I understand the imperative, I find science fiction that adopts its own slang to be a hit or miss concept. It’s the kind of thing that is immediately distracting but can actually bolden the work over time particularly if it feels like it has an honest etymology. Here the kids speak with slang like “dekh” (as in “see” or “watch”), “kopa” (short for copacetic or “okay”), “turge” (for turgid, “hard-on/boner/etc”) and of course the ubiquitous “frack”, and by the end of the book it’s less jarring, but it never gets to the point where it feels unforced or inorganic, the product of a mind constrained by proper English and grammar.

Groan Sudzuka is a familiar name to me, having read his work previously in the underrated and short-lived Outlaw Nation, as well as numerous other places over the years. He’s got a knack for character definition, giving each person defining features and traits in his simplified, classic cartooning style, resembling somewhat a Marshall Rogers or Jose Luis Garcia Lopez. However Sudzuka is not a premiere artist. While he tells a story cleanly, there’s little pizzazz, there’s not a lot of background detail or technology in his work, especially here, which makes the world of A.D.D. pretty sparse looking and uninteresting. His action sequences, which revolve around the group playing their shoot-’em-up games, are uninspired. One sequence finds the kids simply shooting at one another as the carve up and down an extended half-pipe. Video games can take you anywhere, and they’re firing guns at each other on skateboards on a half pipe? Similarly colorists Tanya and Richard Horie don’t do anything at all unique with all that empty space Sudzuka leaves them with. It’s status quo comic book coloring with little style and no added value to the atmosphere of the storytelling.

Were this a $7.99 one-shot or a 3-issue mini-series, I would be a little more lenient in my rating of it (only a little) but as a $25 hardcover it’s not nearly insightful, challenging, poignant, or entertaining enough to deserve the price tag afforded to it.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Marksmen #5 (Image Comics, $2.99)

Marksmen #5 (Image Comics, $2.99)

By Bart Bishop

The post-apocalyptic setting has become a genre unto itself. Although it existed before, the Mad Max movies cemented the concept into a formidable structure that has been mimicked ever since. A recent offering includes The Book of Eli, which added a unique twist on the old trope by making the main character a samurai, and a further twist by having him be played by Denzel Washington. Most stories set after the end of the world could be interchangeable with another genre: the western. The desert landscape lends an easy backdrop, and a forum for analyzing the cyclical nature of civilization and technology. Marksmen, the 6-issue mini-series from Image Comics, of which the fifth issue came out this week, tries its hand at this and succeeds in telling an entertaining story with little to say.

Marksmen takes place in a not-too-distant future, approximately fifty years from now. New San Diego, a self-sustaining technological utopia, is the only known civilization left on Earth…as far as its citizens know. Out into the wastelands is sent Drake McCoy, the protagonist and audience surrogate. Fending off cannibals in search of codes to reactivate a NASA satelite, McCoy encounters a band of nomads who claim to be fleeing Lone Star, a mysterious city of religious zealots and oil powered machinery. This sets the stage for war, as an army from Lone Star attacks New San Diego, wanting the solar power technology it possesses.

Writer David Baxter, who I’m unfamiliar with, keeps the plot moving and knows how to parcel out revelations, characterization, and world building at an engaging pace. The problem is there is very little in the way of originality here: every inch of paper is derivative of another work of popular fiction, with homages bordering on plagiarism. That’s understandable, as there are no new stories, but a master storyteller knows how to remix the old to make it feel new. Homages and allusions when done by, say, Quentin Tarantino serve a purpose: Beatrix Kiddo’s journey in Kill Bill through a variety of trials and genres, from kungfu to Anime to the Old West, serve to challenge the audience’s expectations and cultural stereotypes on race, gender, and violence. Nothing here comes close to that.

Take the lead character. A rival refers to him as “a loner, [and] a misfit” in the first issue, but subsequent issues prove him to be a team player and competent leader. There is nothing in the way of a story arc here: McCoy is promoted and employs traits he already possessed. The accuser, Hercules, has a right to be hesistant: McCoy is promoted from Sergeant to Lieutenant by his parents, General McCoy and Doctor Heston, in a blatant moment of nepotism. At least it would be appear to be favoritism if McCoy shared any substantial “screentime” with his parents. I swear he has one conversation with his father and shares two words with his mother in all five issues.

Speaking of Hercules, the Marksmen are Team Olympus, and all the members have codenames taken from mythology or classical literature. McCoy, for instance, is codenamed Ulysses, while another member is Robin Hood. These names offer shallow personality shorthand for thinly sketched characters and motifs (Hood uses a bow, Shiva is Indian). Still, it’s at least an attempt at social commentary that although the world is in ruins (no explanation why, as most of the animals are said to be dead but there’s no mention of radiation), the people of New San Diego have movies, video games, and even sunglasses that double as a webcam, broadcasting their every move. Everyone, therefore, is too jacked in to youtube to notice the world around them.

This, however, is where Baxter’s themes get muddled. Yes, the masses are appeased by their entertainment, but this is true of both the citizens and the powers-that-be. There appears to be no organized form of government and yet society flourishes, and if anything a true form of democracy has been established with the use of the Internet. Lone Star, by contrast, is a Christian dictatorship led by an old Hollywood caricature named the Duke. There’s a noble attempt in the second issue at portraying the Marksmen as murderous thugs; this would’ve been a provocative opportunity to create sympathetic antagonists, showing a situation in which there is no moral high ground but only human nature. This all collapses by issue five, however, as the Duke is revealed to be a torturous madman with little shading, a not so subtle criticism of the United States and specifically the Bush Administration.

This series is really a showcase for artist Javier Aranda, who knows how to stage big action spectacle with snazzy gadgets versus old fashioned junkers. By the time a Monster Truck EMP device flies through the air in issue #4, all of the inane dialogue and one-dimensional characters are forgotten. Aranda doesn’t fare as well with the quiet moments, when the comic veers into soap opera territory, as his characters look plastic up close and details are inconsistent (General McCoy’s buzzcut fluctuates from planel to panel, as does Heston’s age). Aranda’s characters are all a little too healthy and shapely for the apocalypse, with t&a emphasized with the Cammy character in particular. Still, the Mass Effect/Fallout inspired suits are cool, and the fights are well choreographed and have a clear sense of weight and geography. The cover by Tomm Coker, as well, is a striking image; it’s sketchier than the interior art, but has a unique and shadowy style. Unfortunately it tries six months too late to capitalize on Occupy Wallstreet.

Baxter has created a microcosm in which to discuss big issues, but his message is confused. He comes down on the side of NSD as a benevolent technocracy, but then muddies the water by depicting the Marksmen as bloodthirsty and McCoy as riding a horse when there are buggies available. If this is meant to blur the line between the two cities, as with the revelation that Lone Star does have more advanced weaponry, it’s unclear. Instead these plot points are left sitting there, like much of the potential in this comic. This is ultimately brisk reading for action/sci-fi fans, but be wary of the armchair philosophy and sloppy politics. Issue #5 does end with a cliffhanger, however, that is so earnest as to border on high camp.

If only the rest of the series had embraced such ludicrousness, this might have been something special.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Deadpool #49.1 (Marvel, $2.99)

By Adam Prosser

I’ve got a friend who’s a pretty big fan of Deadpool. “Rob Liefield,” I always sputter weakly in response to his attempts to turn me on to the character, “Overexposed. 90s remnant.” To which he replies, “Joe Kelly. Fourth wall smashing meta-comedy. Juvenile energy, self-parody. The South Park of Superheroes.” (Yeah, we communicate entirely in sentence fragments.)

The glut of Deadpool material certainly helped my resistance to the character, with the assumption that anyone that overexposed couldn’t maintain any consistent level of quality. But the covers frequently made me laugh, and with the imminent “death” of the character coming up in the next (?) issue, I became sorely tempted. When I discovered that this issue was a musical, the die was cast: I finally purchased an issue of Deadpool.

While perhaps not as gut-bustingly funny as the comic’s been rumoured to be at times, this issue is a tremendously entertaining romp, and yes, the musical aspects are well done. There’s either no plot or too much plot, depending on how you look at it, as (after a perfunctory run-in with some bad guys) the Merc With a Mouth recaps the events of his current series in musical form, with an array of special Marvel guest stars joining in. (If you want to be pedantic, the whole issue apparently takes place in his head, but does that kind of qualification even matter with a character like this?) And in case you’re wondering, the songs are all set to the tunes of pop hits—there’s even an online musical component–allowing you to sing along, if you’re so inclined.

It’s ironic that a character who was once the epitome of what was wrong with superhero comics has become something so fun, imaginative and energetic. It speaks to the genre’s ability to spin straw into gold, and almost makes the case for the “evolution by committee” to which most superhero comics are subject. Almost. At any rate, after fighting it for years, I’m now in the awkward position of maybe wanting to pick up another Deadpool comic. Dammit.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

You Really Should Be Reading Wonder Woman

by D.S. Randlett

Remember When the first issues of Red Hood and the Outlaws and Catwoman came out and we were all very angry? It was a perfectly justifiable anger, I think. Here were yet more comics that sought to have very sexualized female characters at their centers. In Red Hood’s version of Starfire, we had a (willfully?) amnesiac sexpot, which reflected what was at the core of Catwoman’s desperate humping of Batman on her title’s final page: these women need dick because they’re fucked up. Edgy.

At the time, many pointed fingers at the superhero genre’s objectification of women, and a few probably made the (wrong) case that the genre was no less exploitative of men. This whole discussion seemed to miss the forest for the trees in my estimation. The problems that superhero comics have with women and sexuality are the problems that western culture has with women and sexuality. In the vast majority of popular entertainment, we rarely depict our sexual lives within the emotional contexts that they are actually lived.

Thankfully, there are always exceptions. Hell, some of the best representations of human sexuality that I’ve ever seen in popular media have been in superhero comics. Right now I’m thinking of some instances of Kurt Busiek’s Superman work, specifically Lois and Clark’s dance in the Metropolitan sky early in his run with Carlos Pacheco, or the intimacy of Lois and Clark lounging in bed in Secret Identity. Or Superman flying above the New York skyline. “If I sound smitten, don’t read too much into it,” he tells the reader, “it’s just because I am.” Of course sex in real life doesn’t always gather such tender associations around it, but I think that these moments show a rather adept understanding of sexuality on Busiek’s part. Most popular entertainment in American culture seems to be comfortable when it thinks of sex as penetration: sexuality tends to be about who we want to fuck and not about who we want to love, even if only for an evening or a moment.

Thinking about this, it strikes me as odd that no one has talked about Brian Azzarello’s run on Wonder Woman all that much. Azzarello and co. are definitely crafting something here, and it’s unlike anything coming from the big two publishers at the moment. As it stands Wonder Woman might be my favorite superhero comic on the stands, which is something I’ve never been able to say before. But then, I suppose that it is only nominally a superhero comic, as it reads more like early nineties Vertigo, in the best possible sense.

Whereas comics and media with highly sexualized female leads are only interested in the surface dimensions of sexual experience, Azzarello’s Wonder Woman pretty much eschews the cheesecake mentality in favor of exploring the meaning of sexual experience and its role in forming individual identity. From the book’s first pages, Azzarello starts to explore the different faces of sexual experience, which he does through the gods. Apollo entertains some call girls atop a very tall penthouse building, but instead of a straight up depiction of the sexual act, we get a scene in which Apollo uses these three women in a prophecy ritual. It’s sex as a vehicle for male aggrandizement. Apollo gets what he wants, and then the women are burnt up, their use fulfilled.

And then there’s Zeus, who is a bit of a mystery as far in as issue 5. He has gone missing, and this has left a power vacuum on Olympus, and several gods have started making plays for his throne. His sole depiction comes in issue 3. It is of course, crucial, as it comes during a flashback to when Hippolyta, Wonder Woman’s mother, slept with Zeus. Zeus sleeping with women who aren’t Hera is a common occurrence in Greek mythology, and it is here too. Most Greek heroes are sons of Zeus, and they achieve heroic status by overcoming the machinations of Hera. What’s worth noting is that these dalliances so far have always been consensual in this particular run. A young woman named Zola slept with Zeus while he was disguised as a truck driver, a funny riff on some of the more absurd ancient iterations of this pattern, and then you have Hippolyta. The episode with Hippolyta seems to express Zeus’ sexual energy as the flipside of Apollo’s. Hippolyta and Zeus begin their encounter through combat: she is warding off a male intruder to the Amazons’ Paradise Island. Their fighting is an exchange of powers in conflict, their lovemaking becomes an exchange of power through consent.

Which brings us to Wonder Woman herself. It is revealed that she is the product of the union between Hippolyta and Zeus. Up til now, she has believed that she was the perfect Amazon, constructed by the creative feminine powers of her mother alone, a clay statue given life. The reality is that that old story was a sort of armor (nakedness, vulnerability, and armor are a few prominent visual motifs in this series) to protect Jove’s daughter from the wrath of Hera. I have no idea what fan reaction was to this, but I think that this makes the origin story even more in line with classical myth and adds a bit of tenderness to Wonder Woman’s origin. It also turns Wonder Woman on her head. If we stick with the original origin, Wonder Woman is basically asexual, meant to basically be the platonic form of the feminine. But who is that?

Azarello is essentially flipping the script on the Amazons. They are essentially making the same cultural mistakes in how they view sex as we are, and for most of her life Wonder Woman has played right into that narrative. Now, she must come to grips with the fact that she is, in fact, a sexual being. Traditionally, Wonder Woman has been a character stuck between the realities of the world of men and her Amazonian ideals. Now, she is stuck in between who she thought she was, essentially asexual, what she actually is, sexual, and the many faces of sexuality as represented by her divine kin.

It’s a thrilling place for the character to be in, because it’s a place we’ve all been in to some degree. Every month in the pages of Wonder Woman, the themes that Azzarello is exploring deepen, or open up in unexpected ways. If you haven’t you really need to check it out.

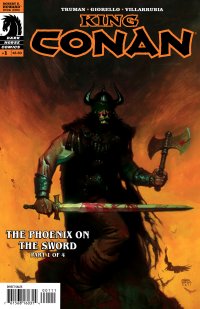

King Conan: The Phoenix on the Sword #1 of 4 (Dark Horse, $3.50)

King Conan: The Phoenix on the Sword #1 of 4 (Dark Horse, $3.50)

By Jeb D.

While I was sort of lukewarm on Arnold Schwarzenegger’s two Conan films (a friend and I had once fan-cast a Conan film, and tabbed William Smith for the role; by the time the film actually got made, he wound up being Conan’s dad), these days, he might not be a bad choice for the on-again-off-again possibility of a film based on maybe my favorite Conan period: “King” Conan. That isn’t to say that’s where Howard did his best writing (far from it), but the idea of the aging warrior with the uneasy crown facing insidious political threats that will require more than a brawny sword-arm to defeat would not only seem to be in the ex-Governator’s current wheelhouse, but it gave Howard’s Hyborian age a texture and context that went beyond, and enhanced, the weird monsters and frigid-but-secretly-man-hungry princesses we associate with the typical Conan story. Howard actually tried a similar trick with Kull (in fact, “The Phoenix on the Sword” wasn’t originally a Conan story: Howard repurposed it from one of his Kull stories), but the greater context that Howard invested in Conan’s life story give it an extra resonance.

We open with Conan now the middle-aged king of Aqiulonia, finding that the responsibility of kingship weighs more heavily with tedium and ennui than anything else: two elements that can easily dull the warrior’s edge. I haven’t read the original story in a while, but my recollection is that writer Tim Truman hits harder than Howard did on the ethnic resentment that is building in the background: Aquilonians are chafing at being under the firm hand of an upstart Cimmerian, and there’s a secret conspiracy afoot to take down the king by conspiring with his ancient enemy, Thoth-Amon. Since taking over the reins of Dark Horse’s Conan license, I’ve felt that Truman’s exposition is a bit more “tell-not-show” than Kurt Busiek’s was, and the long dialogue sequences here, though nicely in the Howard idiom, sometimes feel as though they’re simply an attempt to distract the reader from the relative simplicity of the plot being hatched. Still, getting the heavy lifting out of the way in the first issue should clear the decks for plenty of bloody mayhem in the next issues.

Re-teaming with Truman is artist Tomas Giorello (with colors from Jose Villarrubia), and their Hyborian collaboration continues strong: Giorello’s able to mix some of the Frazetta-style poetry with which Cary Nord launched Dark Horse’s Conan, with the sanguinary, harder-edged style that John Buscema and Ernie Chan brought to Marvel’s Conan magazines. While most of the “action” here takes place in retrospect, its immediacy never lets the reader forget just how lethally high the stakes are.

Of course, no matter how much atmosphere Howard injected into a story, they tend to wind up in the same place (he understood the action writer’s dictum of “when in doubt, have a man come through the door with a gun” before Chandler expressed it; though in Howard’s case, it would be a beast, a broadsword, and a babe), and my only real reservation about this comic is the self-contained nature of a four-issue miniseries: setting Conan’s perilous reign into an ongoing series might allow for more breathing room, and open up some other storytelling options. But, then, for better or worse, that wouldn’t be Howard’s vision, and Truman continues to do a fine job of servicing that vision, particularly when he’s as ably supported by the art team as is the case here.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars