Babel is what Crash could have been if Paul Haggis were a better director. Alejandro González Iñárritu and longtime partner Guillermo Arriaga once again bring a fractured narrative to an otherwise straightforward story that contains supposedly deep commentary about the human condition. This is probably the last time they’ll be doing this, since Arriaga and Iñárritu had a very public break-up earlier this year. And not a moment too soon – Babel is not as fractured as 21 Grams or Amores Perros, but here the style is at its most useless, and really only exists to hide the narrative’s gaping holes of logic and reason.

Babel is what Crash could have been if Paul Haggis were a better director. Alejandro González Iñárritu and longtime partner Guillermo Arriaga once again bring a fractured narrative to an otherwise straightforward story that contains supposedly deep commentary about the human condition. This is probably the last time they’ll be doing this, since Arriaga and Iñárritu had a very public break-up earlier this year. And not a moment too soon – Babel is not as fractured as 21 Grams or Amores Perros, but here the style is at its most useless, and really only exists to hide the narrative’s gaping holes of logic and reason.

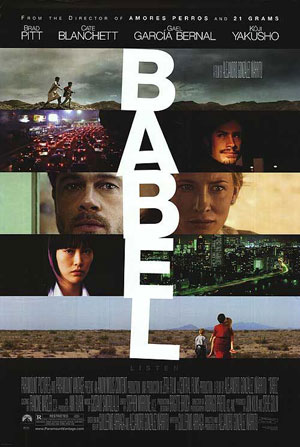

There are essentially four stories in Babel: one features Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett as American tourists in Morocco trying to overcome the recent death of a child when Blancett is suddenly and mysteriously shot; the bullet comes from two local sheep herding boys who have been playing with their father’s gun; meanwhile, the nanny of the Americans needs to go to her son’s wedding in Mexico, but since no one can come take care of the children she watches, she unwisely takes them with her; and in Japan the man who originally owned the gun has a deaf daughter who is sexually confused and looking for human contact. All of these stories are connected, but none actually cross over in a serious way – there’s no third act where everyone comes together. And that’s just as well, because Iñárritu and Arriaga have already stacked the deck so badly that a third act meet-up would be like a hand with five aces.

The Pitt/Blanchett story is alternately gripping and frustrating. Blanchett is shot while riding a tourist bus in the middle of nowhere; she is taken to a local village for what little medical help they can offer while the Moroccan and American governments bicker about how to handle the situation; meanwhile the other tourists gets pissy about being stuck in the middle of nowhere. That element feels completely arbitrary – Pitt doesn’t want to move his wife on the bus but won’t let the bus leave, and on the other side the other tourists feel like they’re acting like assholes just for the sake of conflict. Pitt and Blanchett get some heavy scenes, and anyone who ever had a golden shower fantasy involving Tyler Durden will be psyched, but otherwise this whole segment just slowly peters out.

The kids who accidentally shoot Blanchett are featured in a better story, possibly because the life of a Moroccan shepherd is interesting as something unknown. I don’t know how truthful the depiction of hardscrabble desert life is, but it feels honest and true, especially in the small details like the hormonal boy peeping on his sister in the bath. Still, this segment illustrates one of the main problems with Babel: the kids keep on making bad choices, and so eventually does the father. The movie’s theme is about lack of communication, but it seems to really be about making boneheaded decisions.

Nothing better illustrates that than the storyline with the nanny taking the two kids to Mexico. The only reason there’s a fractured narrative in this film, I believe, is to hide the massive story problems with this segment. We open with the nanny on the phone to Brad Pitt, who is in a hospital with his wife (this is not a spoiler since it’s one of the opening scenes of the movie). The nanny explains that she needs to get to Mexico for her son’s wedding, but Pitt says there’s no one else to take care of the kids. At the start of the movie this makes sense, but as the story unfolds we see that Pitt and Blanchett’s travails are international news. Because of the way the timeline is tinkered with, it’s easy to lose sight of that, as the nanny’s story SEEMS to come to a climax at the same time as Pitt’s, but the truth is that hers begins after his ends. Following me? I hope so, because here’s the rub: she has to take the kids with her to Mexico because she can’t find anyone to watch them. After Pitt and Blanchett are on every news channel on Earth this conceit becomes stupid – in America today the nanny couldn’t have walked out of the house without bumping into Access Hollywood and Inside Edition vans in the driveway. Further, every neighbor in a two mile area would be at the house, looking to help. It’s sheer nonsense, and it’s nonsense engineered by the filmmakers. It’s just as fake as any of the pseudoscience Dilithium Crystal nonsense that saves the day on any given Star Trek episode, but at least the science fiction show was more straightforward about being full of bullshit.

That’s just the start of the problems with the nanny’s story; she continues to make astonishingly bad decisions, including being an illegal alien and trying to just jaunt back and forth over the border, and getting into the car with her very, very drunk nephew. I feel like Arriaga and Iñárritu are trying to make some kind of statement about the borders that divide us, but I could only keep thinking of how truly stupid this woman was.

The best storyline may be, not coincidentally, the least connected to the other three, and as such exempt from most narrative trickery. The Japanese segment has some similar elements to the Moroccan shepherds in that Iñárritu brings us inside a strange world – in this case that of deaf Japanese schoolgirls. This is also the story that has the clearest emotional throughline, very much thanks to actress Rinko Kikuchi, who is able to bring us inside her character’s torment and loneliness with just facial expressions and body language. It’s a gorgeous and brave performance, and with her story you can almost glimpse what this movie could have been if it were more honest.

Her story also has a moment that shows what’s missing from the film as a whole: in one scene Rinko and friends go to a rave and she has a moment of pure ecstasy (Iñárritu misses an opportunity here – he drops all sound out in the rave, while the truth is that a deaf person would be able to feel the very, very heavy bass. Some deaf people love to go dancing just because of that). It’s a real moment, and it’s one that feels all the more wonderful because there’s so little joy in the film. It’s joy that’s missing; again and again Iñárritu and Arriaga show how we’re all connected as people, but they only show that connection leading to pain or catharsis, which is technically just pain that turns out OK. But there’s no sheer happiness. Why don’t we see a guy at a bar watching Pitt and Blanchett on TV, and turning to the woman next to him and sparking a conversation about the events and falling in love? That happens. That’s a valid part of how our lives are connected – your misery ends up leading to someone else’s genuine happiness. Sadly, Arriaga and Iñárritu aren’t interested in exploring this; they’d rather just play with their own stacked deck that speaks to their pre-decided theses.

It is almost unfair to compare Babel to Crash – Iñárritu has crafted a film that is leagues beyond anything that Paul Haggis could come up with. But they’re both the same kind of movie – basically dishonest movies that create jury-rigged situations to lead us to a very specific conclusion. The bummer is that Iñárritu and Arriaga are way too good as filmmakers to be allowed to get away with this kind of cheating. Maybe now that they’ve split their partnership they can explore different, more organic, avenues of storytelling.