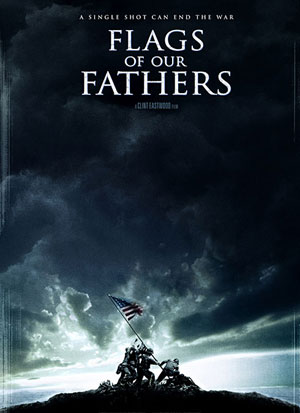

I wonder when Clint Eastwood decided to make a companion film for Flags of Our Fathers, his movie about the famous photo of the flag raising at Iwo Jima in WWII. Did he decide to make the other film (Letters From Iwo Jima, a look at the bloody battle from the Japanese point of view) after he had come far on Flags, or did he take elements from Flags and put them in Letters? Watching Flags of Our Fathers I couldn’t help but feel like something was missing from this movie, like an element that was needed to make the film actually work was gone. Flags is lopsided, a movie that never quite works as well as it should.

I wonder when Clint Eastwood decided to make a companion film for Flags of Our Fathers, his movie about the famous photo of the flag raising at Iwo Jima in WWII. Did he decide to make the other film (Letters From Iwo Jima, a look at the bloody battle from the Japanese point of view) after he had come far on Flags, or did he take elements from Flags and put them in Letters? Watching Flags of Our Fathers I couldn’t help but feel like something was missing from this movie, like an element that was needed to make the film actually work was gone. Flags is lopsided, a movie that never quite works as well as it should.

Part of the problem is the film’s jumbled chronology. It’s not that movie – which takes place alternately and sometimes randomly in the modern day, at the battle of Iwo Jima and at a war bond tour directly following the battle – is hard to follow. The problem is that the modern day stuff is utterly superfluous and feels like the most extended epilogue in the history of film while the war bond stuff is not as interesting as Clint seems to think it is. The problem with the Iwo Jima stuff is that there’s not enough of it.

Some people will scoff at that, saying that Clint never set out to make a standard war film, and I recognize and appreciate that. The problem is that the story Clint wants to tell – the truth behind that image and how it affected the men in the photo – is never as cinematic as when they’re on Iwo Jima.

Three of the men in that photo survived the battle. As the war against the Japanese in the Pacific heated up, the US was facing a dire situation; money had run out and it was becoming obvious that the Japanese would not give up any time soon. It seemed like the Japanese willingness to die would force the US to sue for peace. The war effort could go on if the country could raise some money, but the public was feeling cynical about the long and costly war, especially as the European theater wound down. Previous bond drives had failed spectacularly. But when that photo of five Marines and one Navy corpsman raising the American flag atop Mount Suribachi made front pages across the country it struck a chord, re-igniting the fires of patriotism in the public. The three surviving men – Navy Corpsman John Bradley and Marines Ira Hayes and Rene Gagnon – were plucked from the frontlines to become the centerpiece of the biggest bond drive yet.

But for these men the meaning of that picture wasn’t as clear as it was for everyone back home. The flag raising happened on day five of the battle – the fight would rage on for thirty-five more days. And because none of the men’s faces could be seen in the picture, the naming of the three dead men became confused. Also, the picture, which was so dramatic looking, actually captured a fairly mundane moment – the original flag that was raised on Mount Suribachi had been taken down for political reasons, and this was the replacement. On the war bond tour Ira Hayes, a Native American, had to deal with being a hero for something he didn’t consider heroic while also being discriminated against; he fell deeper and deeper into the bottle. Gagnon, meanwhile, took right to the publicity. As far as the movie indicates, Bradley was just there for the ride.

For the men the focus on the picture didn’t make sense. The real heroes fought and died in the days before and the days after that picture was quickly, almost accidentally snapped. But Clint focuses just as narrowly on that flag raising; the fates of the other three flag raisers (and the misidentified man, who took part in the first flag raising) are shown almost in a montage, like something out of Goodfellas. More time should have been spent on these men and what they endured rather than focusing way too much of the film on the three survivors and their tragical history tour. In the press notes Adam Beach, who plays Ira Hayes (made extra famous in a Johnny Cash song), says that he liked the role because he got to play something more than a stoic Indian. After the third or fourth time Hayes breaks down weeping I wished for a wooden Indian.

How many drunken binges does a movie need to show you to prove a character is a drunk, especially when other characters comment constantly on his drunkenness? How many times do we need to see Hayes and Bradley react poorly to Gagnon’s thirst for the spotlight? And how much does Gagnon need to be smeared, along with his girlfriend, who comes across as nothing short of hateful? I found myself puzzled – the fact of the matter was that the war effort needed these men to be icons, and yet the movie seems to despise the one man cut out to do that job.

What’s doubly frustrating about the Gagnon smear job is that Clint understands that image is as much a part of winning a war as superior firepower. Understanding this, and understanding that the men on the bond tour were probably doing their country more good than they ever could by bleeding out in the South Pacific reduces a lot of their emotional issues to survivor guilt. The annoying voice over at the beginning and the end of the film says many men who served in WWII didn’t like being called heroes, which is admirable, but the fact that the movie avoids is that you can’t decide who is a hero – the public does that. And like it or not, the men in the Iwo Jima picture were heroes, and I don’t think it was because they were raising the flag on that island but because of what they represented. What makes the picture work is that we can’t see these men’s faces, making them not John Bradley or Ira Hayes but every soldier; the movie even acknowledges this.

The message that image counts echoes as a warning today; when the dominant image of the Iraq war is a man with a hood on his head being tortured – just as faceless as the men raising the flag – you know our effort is in trouble. In fact Paul Haggis’ heavy handed script makes sure that, just in case we don’t understand this from the context of the film, characters will tell it to us; an Iwo Jima vet tells Bradley’s son in the modern day that the famous picture of a South Vietnamese officer blowing out a villager’s brains lost us Vietnam.

Flags is never content to just show us what it means, it must tell us as well, preferably in a speech. During one of Hayes’ many breakdowns the military liaison traveling with him gives this whole speech about how the men who died wouldn’t feel any more like heroes than he does had they lived, blah blah blah – it’s all stuff we get from the characters and story. But for those of you in the cheap seats – or the voters in the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences – here it is in easy to understand pablum form.

These scenes again and again sabotage what would otherwise be a fine movie. With half of the bond tour content cut and with more time spent on Iwo Jima, Clint could have still told the same story without pandering. Plus he manages to make the war scenes his own – while there are some surface similarities to Saving Private Ryan, aka the modern war film Rosetta Stone, his battle of Iwo Jima has a unique and intense feel to it. Clint creates a fascinating topography of hell here, and the amphibious assault is unrelenting.

But the treacle is just as unrelenting, and takes up more screentime. The odd decision to essentially end Iwo Jima on day five and fill in the rest of the gaps with quick scenes of characters dying leaves Flags of Our Fathers with no climax. The bond tour ends, the men move on, Ira Hayes runs into trouble again and again, the photo becomes the basis for the USMC War Memorial. The movie just chugs on, long past its obvious finale, headed for the deadliest of sentimental dreck. Anyone who choked on the saccharine end of Saving Private Ryan (“Tell me I’m a good man.”) should run from the theater once the war bond tour ends. John Bradley’s son, James, becomes interested in Iwo Jima and his father’s role there; like so many men of his generation, Bradley never talked about his war (which, by the way, makes the endless emoting of the war bond tour feel all the more alien). The son interviews other vets for insight, and is there at his father’s deathbed for some truly wince-inducing moments.

Thankfully Clint ends the movie on the right note, which a series of pictures of the real men and the real battle of Iwo Jima. It’s stunning how exactly he recreated the look of those photos and those dirty black beaches, and as you sit transfixed by these images you wonder why most of the movie took place in much less interesting locales. Then you tear your eyes away from the pictures just long enough to verify that it was indeed Luther from The Warriors playing Harry Truman, which is some damn weird casting.

I don’t think Flags of Our Fathers works without the counterweight of Letters from Iwo Jima, but that’s purely speculation at this point. On it’s own Flags of Our Fathers is terribly disappointing because there’s enough goodness in here to make the bad stuff all the more obvious. Flags of Our Fathers is a movie that really, really wants to be about something and it really, really wants you to know that. It would have worked better if it had just been about something and let us find it.