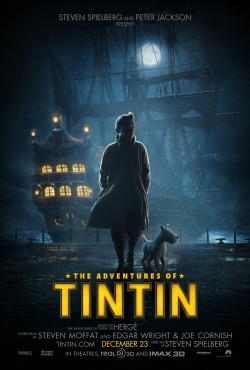

An adaptation of the classic (and ancient) Hergé comics series, The Adventures of Tintin is a film I suspect only two people in the known universe wanted to see. But when those two people are director Steven Spielberg and executive producer Peter Jackson, that shit’s getting made anyways.

An adaptation of the classic (and ancient) Hergé comics series, The Adventures of Tintin is a film I suspect only two people in the known universe wanted to see. But when those two people are director Steven Spielberg and executive producer Peter Jackson, that shit’s getting made anyways.

There’s an affectation in regards to Steven Spielberg’s most recent work that I find troubling. It’s the notion that mindless, over-the-top action, expansive set pieces and Spielberg’s ever-present Child-Like Wonder™ can serve as substitutes for authentic story, characters and pacing. Yes, Tintin is a gorgeous film – filled with amazing visuals and action that assaults the senses. But it’s overload, and an experience that’s as altogether dazzling as it is emotionally vacant.

The only thing that feels even remotely reigned in is Spielberg’s use of 3D. It’s so mild in fact that I wonder why the director went this route at all. Aside from muting some beautiful color work on the part of the animators (especially in the desert and palace sequences), the 3D is so subtle to the point of being ineffective. I’ve long believed that the gimmickry of 3D lends itself more to the schlocky goodness of a Pirhanna 3D or My Bloody Valentine. The immersion argument, that 3D brings the viewer more in touch with the action, simply doesn’t hold weight.

Where the 3D fails, the motion capture work picks up the slack. This is the first mo-cap film where, aside from a few odd facial ticks from Tintin himself, I wasn’t completely creeped the fuck out. As always, the folks at Weta Digital use their incredible talents to inch the medium ever forward. Considering the totality of their work with effective characters like Gollum, Caesar and Kong, perhaps they’re the only players capable of pulling off the mo-cap game at this time.

Hopefully you like watching Tintin read. He's going to do it a lot.

Fitting that all of the above-mentioned performances are from Andy Serkis – given that his Captain Haddock is what saves Tintin from being a complete waste of time. The only fully-realized character in the film, Haddock is the true star of the picture and the driving force for what little plot exists. His mind holds the key to finding treasure hidden by his pirate ancestor, Sir Francis (also Serkis). And he blows everyone and everything around him out of the proverbial water.

With the added benefit of digital make-up, Serkis is a modern-day Lon Chaney – a “Man of a Thousand Faces” whose immense talent and technical resources of the time allow him to disappear into any role he inhabits. I would be comfortable with Serkis landing some awards love for Haddock, the performance is that good. I think this is a pivitol time for Serkis’ career, as being pigeonholed strictly as a mo-cap worker would be doing a disservice to both him and us. Above all else, he’s a most gifted actor. No more evident than in Tintin, where he rises above weaker material. It’s a credit to Serkis that the film doesn’t start until Tintin finds Haddock.

Andy Serkis' Capt. Haddock is the real star and only reason to see the film.

I attribute this to the fact that Tintin (Jamie Bell) is the Benjamin Harrison of fictional characters, his role might be important but he’s not doing anything of particular worth with it. And I don’t blame Bell. Whatever talents he might have injected are lost in the tedium of an uninteresting Boy Scout. When we meet Tintin, he’s getting his self-portrait done. When he needs to solve a mystery to advance the plot, the first thing he does is hit the library for a hardcore study session. These are great attributes if you’re self-involved or applying to Harvard (or both). But as an actual lead in a film he’s a grating red menace.

The reason an adventure film like UP works and Tintin doesn’t is because a crucial part of adventure is character growth. Carl Fredricksen turning his home into a makeshift airship and traversing Paradise Falls had every bit as much to do with letting go of his dead wife as it ultimately did reuniting that goofy-ass bird with her chicks. There’s no such development for Tintin, dude just really likes solving mysteries and going on adventures – more Dora the Explorer than Indiana Jones. Adventure should never come at the expense of progress.

Some beautiful work by Weta Digital.

That adventure in and of itself presents an even greater problem. The film inundates with one over-baked action sequence after the next. One scene in particular, where a trained hawk pursues Tintin and Haddock through a crumbling city, represents everything about the film that doesn’t work for me: amidst all this destruction, where’s the danger? There isn’t any, because the only rule Spielberg is abiding by here is that there aren’t any. Every scene needs to be bigger and more ridiculous than the last one.

That’d work if I at all cared about Tintin’s quest for the treasure, but I’m not even sure why Tintin cares about the treasure outside of the ginger gingerly proclaiming “I’m a journalist!” to anyone who’ll listen. With nothing of importance on the line, it’s the cinematic equivalent of watching Spielberg play with his action figures for two hours. And I don’t need that again, I’ve already seen the last thirty minutes of The Lost World.

With any luck, this is Tintin running away from the spotlight.

I went in to Tintin with high, but reserved hopes. Spielberg hasn’t registered with me as a director in some time (War Horse manages a few right steps before drudging itself into a saccharine coma). But I had hope for the writing talents of Joe Cornish, Edgar Wright and Steven Moffat. I think their reservation in bringing any sort of layer to Tintin holds them back and gives the viewer nothing of substance to hold on to.

Sadly, I fear it’s too easy for Spielberg these days. Motion capture gives him the opportunity to put any idea, no matter how ridiculous, onto the screen. I miss the days of old when influences like Doc Savage, old serials, and yes, Tintin, were refocused into profound new works like Raiders of the Lost Ark, derivative as it may have been. But we’re in a time where everything that’s ever existed (ever) is getting adapted, re-adapted, franchised and rebooted in four years to bring you a newer, untold origin story. So while you may not have asked for The Adventures of Tintin, you’re getting it anyways. On visuals alone, Tintin is a great technical exercise anchored by one worthwhile performance. But films aren’t judged on visuals alone.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars