Terry Gilliam was at the ThinkFilm offices doing interviews in a conference room. Right outside the room was a big cardboard sign, the kind that homeless beggars have. It said, “Studio-less Filmmaker/Family to Support/Will Direct for Food.” It was a prop for his late afternoon publicity stunt, when he would go to the Daily Show ticket line and hand out passes for his new film, Tideland.

Terry Gilliam was at the ThinkFilm offices doing interviews in a conference room. Right outside the room was a big cardboard sign, the kind that homeless beggars have. It said, “Studio-less Filmmaker/Family to Support/Will Direct for Food.” It was a prop for his late afternoon publicity stunt, when he would go to the Daily Show ticket line and hand out passes for his new film, Tideland.

Tideland played at the Toronto Film Festival last year to much curiosity and, eventually, sharply polarized reviews. It’s a difficult movie, one that Gilliam knows will divide audiences sharply. As he says in the interview, he fully expects people to walk out of his film. Whatever your take on the movie ends up being, that kind of attitude must be respected – too many filmmakers will do anything they can to make sure their film caters to you. Gilliam remains defiantly maverick.

The star of Tideland is the preternaturally gifted Jodelle Ferland, playing Jeliza-Rose, a girl whose washed up rocker and junkie dad takes her to his old home in the middle of nowhere and dies. Left alone she must survive with just her doll heads and Dickens, her older, retarded neighbor, to talk to.

Gilliam was incredibly gregarious – you could point the man at a topic and he would take it from there. And it soon became obvious that no question would be off-limits. When he says he’s the most honest filmmaker on the planet he’s half-joking, but he’s completely right. This is a packed interview, and we covered a lot of topics – everything from the audience reaction to the movie to his thematic history to his possible upcoming projects (there are some fascinating hints of things that might yet come). The publicist ended this interview after thirty minutes, but it was obvious that Gilliam could go on for much longer.

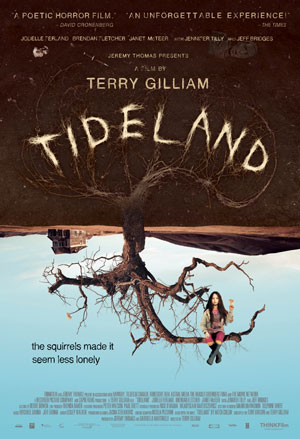

(The image to the right, taken at the Daily Show ticket line, comes from Aint It Cool News)

Q: How did this film come together?

Gilliam: There was the book sitting in the pile of submissions and I read it and thought, ‘Fuck, this is great. This will wake up some people!’ This child’s voice was extraordinary and the situations – it was captivating. I got a hold of Tony Grisoni, who I write with, and threw the book at him and he said, ‘Fantastic!’ I threw it at Jeremy Thomas, and Jeremy said, ‘Great, let’s go!’ And then we couldn’t raise the money.

Q: How did pre-production and shooting go?

Gilliam: It was fast. It was wonderful. What was most interesting about this is that it was like going back to the beginning, in some ways. We had a very short prep period – the shortest I have ever had. The joy was I had to make instant decisions, I could double-think, which I normally do. Things just started to fall into place. That house in the valley, we found that, and then Dell’s house, we found that 2 kilometers away! Everything dropped boom, boom, boom.

When it came to casting, Jeff [Bridges] was always going to do it from way back when. I always thought Jennifer Tilly was terrific, and we got her on. Dickens – Brendan Fletcher is the first person I have ever cast without meeting him in the flesh. He sent this tape that he and his girlfriend had done, and Jesus, this guy was good. Again, because of the time thing I couldn’t piss around.

I wish I could force myself to do this more often, because I really like working that way, and things seem to fall into place. The most terrifying part was Jodelle [Ferland] – we were already into pre-production and we still hadn’t found her. I was right at the edge of telling Jeremy Thomas that I knew we had spent a bit of money but we would have to pull the plug because the girls I had seen were just not up to it. And then this tape came in from Vancouver with six or seven girls on it, and there was this little creature with these amazing eyes and this incredible energy, and I said, ‘Hello!’

Q: You talked about reading the book and thinking this was going to wake people up. At my screening people began walking out when Dickens and Jeliza were getting romantic –  Gilliam: They lasted that long?

Gilliam: They lasted that long?

Q: They did last that long! When you’re making the film do you realize that this is going to drive people from the theater, and are you OK with that?

Gilliam: I thought they were going to be gone with the first shoot-up. I don’t know where they’ll start leaving, but I know that a lot of people won’t allow themselves to connect to this film. They refuse to connect to this film, that’s the problem. My wife says you have to submit.

That scene, the kissing scene, when we were shooting it, I knew… I mean, it’s my favorite scene in the movie, I think it’s an extraordinary scene. And it’s her – it’s her! It was one of those scenes where the 64 year old director is not going to tell the 9 and a half year old girl what to do – the script was there, she knew where to take it. Brendan, on take two or three, completely forgot all of his lines. I said, ‘Brendan, what happened?’ He said, ‘She was mesmerizing, she had complete control of me – my brain just emptied out.’ That’s the power of the little girl in a situation like that.

The point of the scene is that I know the audience will be squirming, because adults come with all the preconceptions and fears and shit that’s in the air. But shooting it I knew what we were doing was completely innocent, and it had to stay that way. There’s a scene later on where she’s in his bedroom, and in the book when he’s getting on top of her his hand is going up her thigh. I said we can’t do that; it’s a really fine line we’re treading here, and if we go over it we’re completely fucked. I know people will be squirming, but at the end of the scene, come on folks, nothing happened. But now they’ll be more terrified – ‘He’s done that for openers… where will he go next?’ [laughs]

I’ve done an introduction – I wish they had shown this to you guys. I did an intro that’s going to be on the film; it’s me in black and white up there saying, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, my name is Terry Gilliam. I have a confession to make. Many of you are not going to like this film. Many of you are going to love it. And many of you are not going to have a fucking clue what to think about it when it’s finished. But to help you for the next two hours, try to become innocent again. The film is shocking because of its innocence – try to recover that. Get rid of your fears, prejudices and preconceptions as an adult. Children are resilient – they’re designed to survive. Drop them and they bounce!’ [laughs]

Q: The scene that really seems to define that is towards the beginning when they arrive at the house and Jeliza starts coughing up blood. Rather than freaking out she starts play-acting as a consumptive in the mirror. It’s like she’s announcing her coping method.

Gilliam: That scene shows that she watches television. She’s watching soap operas all the time, so she’s in that fantasy world. That world is what she thinks the world is. But actually, you said coughing up blood, but she bit her lip. It’s interesting how audiences see films!

Q: Would you say that if Jeliza was more grounded that would be a handicap for her?

Gilliam: I don’t know. You could argue that anybody going through things like that would be surprised when Dickens turns out to be not the sweet creature that he was. Kids are not aware of their vulnerability or their power, either one. That’s what intrigued me to show. It may be playing with the adults in the audience, but when the entire family comes, the kids will have a great time.

Q: You have a habit of taking assumptions that we have and confounding them, turning things around at the end.

Gilliam: Some of that I do consciously and some of that is just how I see the world. In this instance it was in the book, so I can’t take credit for the imagination of the thing, it was there. But with me it’s almost like the naughty child who’s playing with his parent’s preconceptions of things, as kids do.

Just being here in New York I was thinking about how this is the 25th anniversary of Time Bandits. This is a story about a child’s imagination. Time Bandits ends with the parents being blown up, this one starts with the parents dying pretty quickly. I wasn’t even thinking about that at the time, but it’s interesting. I kept thinking, is the world changed or have I changed?

Q: Speaking of being the naughty child – is that something you picked up when doing Help! magazine with Harvey Kurtzman?

Gilliam: I don’t know if I picked it up then. I think I was doing Help! because I was like that. I’m drawn to things like that. I’ve always, from a very early age on, when someone says, ‘This is what the world is,’ I say, ‘Hold on – what about this?’ It’s about always trying to rediscover or redefine or shake people up in their ideas of the world. It may have come from me being brought up as a nice Christian boy who was going to be a missionary and went to university on a Presbyterian scholarship… but I was also making jokes about God and Jesus and the community. People were taking offense and this, and I was like, ‘What kind of God do you believe in that can’t take a joke?’

brought up as a nice Christian boy who was going to be a missionary and went to university on a Presbyterian scholarship… but I was also making jokes about God and Jesus and the community. People were taking offense and this, and I was like, ‘What kind of God do you believe in that can’t take a joke?’

That’s why I always wanted to be Jewish!

Q: When you look back at your career, and you see the thematic similarities between this and Time Bandits, do you think that what you’re doing is staying true to yourself?

Gilliam: I don’t know about staying true. I keep trying to convince myself that I’m doing new things all the time, and I look back and I’m doing the same shit!

Q: You did John Cleese playing with Barbie dolls, like in this film.

Gilliam: I did. You’re right. Shit!

Q: Looking back at Help! magazine…

Gilliam: Everybody was on it. There was Harvey, Bob Crumb. It was fantastic.

And that’s why I still love comic books. Although comic books are getting so irritating, because they’re getting so violent and so ugly, although maybe that’s just a good reflection of what’s happening in the world and the frustration of people. There’s just not as much humor in comics as there used to be.

Q: And people read things like Watchmen and focus on the darkness and not the humanity.

Gilliam: Do you know about his new one? Lost Girls? I’ve got it!

Q: Do you ever think of doing comics?

Gilliam: It’s very weird. Do you know Shekhar Kepur, the director? Do you know Deepak Chopra? Shekhar and Deepak and Deepak’s son Gotham started a comic company in India that Virgin’s Richard Branson put many into, and Shekhur’s trying to get me, to get John Woo, to write comic books. And Hollywood will get excited and make movies out of the comics. He said, ‘Any scripts that aren’t going anywhere, give them to us and we’ll make a comic book out of it and we’ll get Hollywood excited.’

Q: The Defective Detective would be a great comic book.

Gilliam: Somebody did suggest to me doing it as a comic book, or as an animated film, and maybe that’s what has to happen. It’s just sitting there, not going anywhere at the moment.

Q: It’s a good script.

Gilliam: You’ve read it, huh? On the web somewhere? I don’t know how this stuff gets out there! This is what I love about the world. I love pirated DVDs. I love it all – keep it flowing!

Q: This film has a very decayed Southern Gothic, run down Wyeth look, which is very different from many of your other films, which are quite claustrophobic.

Gilliam: It was strange working in Saskatchewan, because coming from Minnesota the landscape is not very dissimilar to what I remember. We had the Wyeth to start with, but that was just a few things. But then it was these huge, open outdoor spaces – but then we had this house, which is decaying and rotting inside, this smoker’s lung. Then we contrasted and juxtaposed the two things.

People say, ‘Wow, how did you shoot those landscapes?’ We just put a camera out there! You’re getting out of that house, and running and playing and leaping and then getting back inside. It’s like breathing – you’re going [breathes in and out heavily] all the time. Jasna Stefanovic, who designed it, is a Canadian designer. She came to me – yeah, I had to work with Canadians. It sounds terrible, but it turned out to be wondrous! – and she put together a little book the night before. The images – I thought, you got it kid. She was actually more disturbed than I am! I kept having to pull it back. But I also thought it was very useful to have a woman designing it since it’s a story about a little girl. The more women I could have working on the film – Leslie Walker, my editor, is a woman. And Jasna was Jeliza-Rose, she was whacko. She lived these characters.

Jasna Stefanovic, who designed it, is a Canadian designer. She came to me – yeah, I had to work with Canadians. It sounds terrible, but it turned out to be wondrous! – and she put together a little book the night before. The images – I thought, you got it kid. She was actually more disturbed than I am! I kept having to pull it back. But I also thought it was very useful to have a woman designing it since it’s a story about a little girl. The more women I could have working on the film – Leslie Walker, my editor, is a woman. And Jasna was Jeliza-Rose, she was whacko. She lived these characters.

There was a great night casting the doll’s heads. There were hundreds of them. And you start to realize you’re not dealing with props anymore, you’re dealing with actors. You say, ‘Is that really Mystique? I don’t know…’ And doing that, playing with doll’s heads, made it clear in my head what each doll meant for Jeliza-Rose.

64 years old and playing with dolls!

Q: How did you end up in Saskatchewan?

Gilliam: They offered us money! It’s supposed to be Texas – in the book it’s Texas. We knew that area looks like Texas, and they’ve got a studio there that was built for Canadian Broadcasting.

That valley, when we got there, is absolutely a magical valley. The Indians – or as they’re called in Canada, the First Nations – there’s something magic about that valley. We hated leaving it. Everything is there. When you’re in a place so wonderful you put it on film. It’s what you do.

And it’s a simple film – there aren’t any horses or special effects. It’s the actors doing things, and the camera doing things. You don’t have this technical nonsense. Even things like when we were doing the underwater house, where you would spend ages developing it and having motion capture cameras – nah. We did it like the old days. I had everybody in the crew putting wires on all the props inside the house. Chairs, tables, everything. We drilled holes in the ceiling of the set. The whole crew was on top, wiggling things, and we had a fan blowing and we shot it as 92 frames, the camera sweeps in, we got the background plate, got it. The whole thing was the way you would never do it if you had a few dollars more, and it all worked.

The most extraordinary thing was the scene when she’s underwater and she’s speaking. We were shooting at 72 frames, and then we had to do the lines, we recorded them, and we sped them up. It was just impossible to understand! [At this point Gilliam makes a chipmunk-like noise] I said, she’s not going to be able to do it so I said, just move your lips and we’ll see how it goes. But it wasn’t working, and she said, ‘Terry, I can do it.’ And she spoke three times normal speed.

Q: Going back to the claustrophobia, what is it about that feeling that fascinates you?

Gilliam: It’s probably like why there’s a cage in all of my films. In every single film. This squirrel got it this time.

So much of my life I feel trapped. I feel like I can fly, but I can’t. My body won’t let me do the things my brain says I can do. I think that’s it, so I’m always pressing against these walls that surround me. I get out occasionally, but most of the time I’m trapped.

Q: The open spaces in this film remind me of Terence Malick. Did you have Days of Heaven in mind?

Gilliam: I watched about thirty minutes of Days of Heaven and I just got so depressed. I couldn’t do that. He shot it all at magic hour – but we don’t have the money to do that kind of thing, so I switched it off. Because it’s so stunningly beautiful.

Q: New World has that too to an extent.

Gilliam: Yes, but less successfully as a film. I don’t know what the hell that’s about.

Q: Terry, with the new regime at Miramax is it possible that you could go back and put together a director’s cut of Brothers Grimm?

Gilliam: That’s the film I made. That’s my cut.

Q: So the rumors that it’s the Weinstein’s cut aren’t true?

Gilliam: There’s so much bullshit on that one. What happened is that we had reached a point where we had done two public screenings and we were about to do a third. Bob came over and saw a reel and a half and said, ‘It doesn’t work.’ I said, ‘You haven’t watched the film, Bob.’ I knew there was going to be a fight to the death. I said, ‘Listen Bob, there’s this other film [Tideland] I have to do because Jeremy got the money. Why don’t you just take the film away and do what you want with it and come back and we can talk about it.’ They then called several award-winning directors and editors to take over the film and nobody did, and I went off and made Tideland, and we came back. We were editing Tideland and I got a call saying, ‘Will you come back and finish Grimm, your cut.’

where we had done two public screenings and we were about to do a third. Bob came over and saw a reel and a half and said, ‘It doesn’t work.’ I said, ‘You haven’t watched the film, Bob.’ I knew there was going to be a fight to the death. I said, ‘Listen Bob, there’s this other film [Tideland] I have to do because Jeremy got the money. Why don’t you just take the film away and do what you want with it and come back and we can talk about it.’ They then called several award-winning directors and editors to take over the film and nobody did, and I went off and made Tideland, and we came back. We were editing Tideland and I got a call saying, ‘Will you come back and finish Grimm, your cut.’

That’s my cut. It’s not my best film, but I don’t know what all the bad reviews are about. I think it’s a good film and I like it a lot! It’s flawed, but there are moments in there that are as good as anything I have ever done. It seemed to me that it’s always about expectations, which I hate. I want to lower people’s expectations so badly that they can come with appreciation! And I think there was a lot of that; I hate the way with the press once the feeding frenzy starts you can’t get away from it.

Q: I think one of the reasons people think it’s not your cut is because one of the expectations people have is that a Gilliam film must have struggle behind the scenes. Every film is expected to be a fight. And there almost always is. Why is that?

Gilliam: There actually isn’t – if I go through the whole thing, there’s Brazil, the most famous battle. That set up the stage for, ‘This guy’s trouble.’ But after that, and in particular my Hollywood films – Fisher King, 12 Monkeys and Fear and Loathing – no fights! That’s the irony of the whole thing. But what happens is that because I have somebody making a documentary or writing a book about it, whatever fights there are, because they’re in print or on film, they become public. Other filmmakers are going through the same thing or worse, but it’s behind closed doors. The only reason I have these documentaries made is that I’m too lazy to keep a diary and I have no memory anymore, so these are my diaries. But it becomes… every filmmaker I know has stories that are worse than mine but aren’t documented.

Q: Is it that you’re more honest than other filmmakers?

Gilliam: Yes, I am the most honest filmmaker on the planet! I mean, the way Hollywood works it’s so much behind the doors and everybody’s encouraged not to be open. I understand why – look what happens to me – but nevertheless, I’d rather have more information out there and people can decide for themselves.

I love DaVinci Code, which they obviously made as this very serious, portentous revelation of the truth and then when they started getting a lot of shit dumped at them – ‘Oh, it’s just a movie!’ Come on, folks! They knew exactly… they thought they were doing an important bit of work, and they turned tail. That’s what I hate – there’s so much bullshit in this business, and I’m happy to let the dirty laundry hang out there.

Q: What are you working on next?

Gilliam: I don’t know. There’s the Quixote thing, which drives me crazy. It just hangs in the air. It’s the elephant in the room always. There’s Good Omens, which is this thing I was working on before Grimm, which I’m still trying to get going. But it’s the cost – what worries me is the atmosphere out there is so frightened and timid. When you’re doing expensive films, they want very safe expensive films. But this is a wonderful book, and I think our script is good too. There’s another one that’s come my way recently that I didn’t write and I’m trying to decide… I can knock it out in six weeks and get it done, get back to work. I’m tempted.

Q: You’d be doing the same thing you did on Tideland, the quick decision-making.

Gilliam: Yeah, but it’s not as good a story. It’s less magical, wondrous, disturbing, anger making. You don’t know anything about this – it’s written by a guy who has never written a screenplay before.

I want to do these things, like Good Omens, but I can’t get them moving. I want to find the producer of my dreams who actually has great power in Hollywood and will help me. I’ve never stayed with one producer; I’m all over the place with producers, which is kind of a bad thing because I’ve never built up – like Brian Grazer and Ron Howard, those kinds of relationships.

Q: Brad Grey is open.

Gilliam: He doesn’t know anything about making films. I want a producer who knows about making films and not just money because otherwise there will be fights all the time.

The guy who was the line producer on Grimm has some Chinese money and he might want me to do something. I like Chinese money! It’s a big epic, and epics are hard. I like the idea of  making a small film like this – you don’t have the weight. Grimm was a quarter of a million dollars a day! You’ve got that on you. And I don’t worry how much we’re spending as long as it’s in the budget, but you have 300 people working for you and everything is cumbersome and everything is slow. There are 700 shots –

making a small film like this – you don’t have the weight. Grimm was a quarter of a million dollars a day! You’ve got that on you. And I don’t worry how much we’re spending as long as it’s in the budget, but you have 300 people working for you and everything is cumbersome and everything is slow. There are 700 shots –

Oh, wait, I want to tell this one! We got so much shit about bad special effects in Grimm. I was in the Carlo Vivari Film Festival and there was this Czech or German journalist who was saying the effects are no good. I said, ‘I’ve been reading about this, I’ve been hearing about this – give me an example of a bad special effect.’ He said, ‘You know the scene where Matt kisses the frog? That’s a terrible CG frog.’ I said, ‘No. That’s a real frog.’ The poor guy just died at that point.

I know that film, I can name the bad shots, but there are 730 others nobody notices!

Q: How do you imagine Jeliza-Rose as an adult?

Gilliam: When we were doing the last shot on the train, I was thinking, what is this child going to turn into? I thought probably she would be with that nice, bourgeois lady and she’ll have a proper upbringing and life will be wonderful and whatever happens to her she’ll always look back on those few days and that period because life was never again as extraordinary and terrifying and wondrous as that.

I look at the pictures of Alice Liddell, who was Alice in Wonderland – and Jodelle looks surprisingly like her – and there she was being photographed by Lewis Carroll and she was a saucy little minx. She had this guy around her little finger. And then you see her in later life and there was a face with no joy in it. Nothing was ever as wonderful as Lewis Carroll writing and telling her these stories. And her manipulating this guy, this poor guy who was entranced with her and who wrote to make her happy. Her life was never that good again. I think that’s what happens to Jeliza-Rose – she’ll be middle aged and bitter and probably successful in business or something.