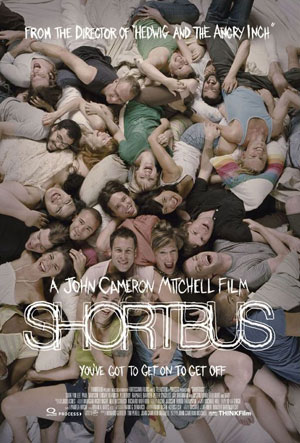

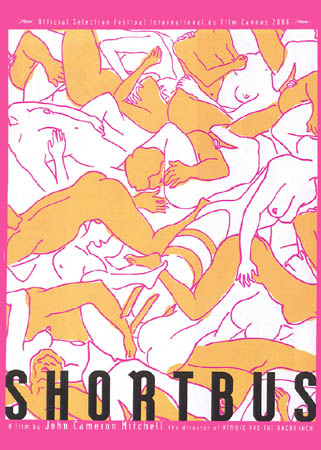

I first heard about Shortbus at the first or second Tribeca Film Festival. John Cameron Mitchell was on a panel about sex in film, and he talked about how he was working on a new movie that would be set in a New York City salon (not the beauty type. Think more like intellectuals) and would feature actors having real sex. I didn’t know what to think – I loved Mitchell’s first film, Hedwig and the Angry Inch. I loved it a lot – but I had not seen a movie that had integrated real sex into the narrative very well – mostly of them were awful, awful films.

I first heard about Shortbus at the first or second Tribeca Film Festival. John Cameron Mitchell was on a panel about sex in film, and he talked about how he was working on a new movie that would be set in a New York City salon (not the beauty type. Think more like intellectuals) and would feature actors having real sex. I didn’t know what to think – I loved Mitchell’s first film, Hedwig and the Angry Inch. I loved it a lot – but I had not seen a movie that had integrated real sex into the narrative very well – mostly of them were awful, awful films.

I wouldn’t see a film that integrated real sex into the narrative well for a couple more years – Mitchell took his time finishing Shortbus, including taking three years for he and his actors to get to know each other and create the characters and situations together. The film was well-received at Cannes, and when it finally got screened in New York I made sure I was at the first showing. I wasn’t disappointed – Shortbus is a very good film that’s about sex and human relationships… and the sex happens to be graphic.

When I spoke to John Cameron Mitchell on the phone a couple of weeks back, he was very tired. He had been doing press all day, and the official premiere was taking place the next day. He used our conversation as an opportunity to sneak in his lunch. Honestly, I was concerned – I’ve done interviews where the talent is tired and/or eating, and they always turned out poorly. Mitchell rallied in seconds, though, giving me great and expansive answers. It’s too bad that John Cameron Mitchell films are so few and far between – I wouldn’t mind meeting him on the junket circuit every year or two.

You’ve been doing press all day – how many times have you heard a variation on the question, ‘If you’re going to have real sex in a film, why not have real violence too?’

Mitchell: I haven’t heard that one before, actually. But it’s funny because you’re equating sex and violence.

Well, the question is.

Mitchell: The question is making an assumption that they somehow have equal value. In violence people get hurt. Sex, you can get hurt, but not when it’s good!

Why do you think it is that there have been so few films that are sexually explicit that are also good?

Mitchell: I think sex on film can sometimes be clouded by eroticism. There are so many layers to sex, but we as Americans tend to focus on only the erotic side. There are so many other sides. There’s an emotional side. And its’ fucking hilarious. The thing is that when you’ve got a hard on, you’re not always laughing. You’re not always thinking about thoughts, you’re not always thinking about emotions – especially if you’re a guy. Even my most enlightened friends are like, ‘How’s the porno film coming?’ because they can’t separate arousal from sex on film, even though novelists and all kinds of other artists have certainly used explicit sex in their examination of life. It kind of makes me wonder if it would be more interesting to de-eroticize the sex and see what was left over, because so many films get so hot and bothered rather than examine and go in-depth.  Certainly European films lately have used real sex and done it very effectively. I think Fat Girl is amazing. But many of them fall in that other trap, where they’re so running away from Hollywood and porn that it ends up that the sex is bleak and humorless… ends in some kind of mutilation, usually. It feels almost like a cliché today now – 9 Songs, Romance, Brown Bunny, all of these things in this really despairing mode that feels to me like it doesn’t respect the full range of stuff attached to sex either. Porn was one slice, and those were another grim slice.

Certainly European films lately have used real sex and done it very effectively. I think Fat Girl is amazing. But many of them fall in that other trap, where they’re so running away from Hollywood and porn that it ends up that the sex is bleak and humorless… ends in some kind of mutilation, usually. It feels almost like a cliché today now – 9 Songs, Romance, Brown Bunny, all of these things in this really despairing mode that feels to me like it doesn’t respect the full range of stuff attached to sex either. Porn was one slice, and those were another grim slice.

I think it comes out of cultural prudery, it comes out of religion, it comes out of the pure terror we have of something so powerful in our lives that we want to compartmentalize it and flatten it out in film.

This is a very New York film. 9/11 hovers over the whole picture, you have a character who is based on Ed Koch. What does New York mean to you?

Mitchell: I was a real patriotic, religious kid growing up. My dad was in the Army. I used to cry at the national anthem. I still feel like I want to, but maybe for different reasons! But I’m still completely moved by the Statue of Liberty, this very traditional idea of America as a refuge for the freak and the persecuted. New York is certainly a distillation of that. The Shortbus is the next window down, if you’re talking Microsoft Windows. And I just love that idea of a bunch of freaks getting together and helping each other out. It’s what art is, it’s what punk rock is. Even when I was a kid going to the Catholic prayer groups was the same thing. And then I realized that the Church was on the wrong path for me, but I still like the feeling I got from those groups.

So the Shortbus. I was on the short bus for a year. It wasn’t because I had a physical disability, but I certainly had a social one. But it’s what I love about New York. Even though artists are being priced out and having to go farther and farther on the fringes of the city or into, God forbid, Jersey, it’s still New York.

You sort of make an apology for Ed Koch and the way he dealt with AIDS. A lot of people might not agree with that.

Mitchell: I don’t really name the person this character is inspired by. What I do say is, imagine there was someone who, because of his fear of acceptance of himself and fear of other people accepting him, actually made decisions that directly, negatively affected people’s lives. Imagine that happening and then imagine the person realized it later and sought forgiveness. The character seeks some kind of redemption, as all the characters do. He even refers to New York as the place you come to get fucked and you come to get forgiven. From a real or an imagined sin.

A lot of the people who come here are told that they are fucked up and they didn’t fit in and that they were sinners. You kind of come here to find out if it was true, and if it was true, to forgive yourself. And if it wasn’t maybe to even forgive the people who accuse you. You have to have that. All of the characters are trying to connect and feel OK about themselves, and they all help each other out. Even the Mayor, who through his impermeability as he calls it, made some terrible decisions or neglected some actions that he should have known better about. There are no villains in the film.

You worked with your cast for three years, creating the characters and building the community. Is that the only way to make a film with real sex?

Mitchell: It seemed to be the best way for me. I’ve seen other films that were successful that used real sex and they weren’t like that. There’s a film called Taxi Zum Klo from 1980 that was a real autobiographical film – the filmmaker played himself and his boyfriend played his boyfriend. I think that’s another way to go; you’re documenting your life in a certain way. That film Fat Girl, the director actually made a film about the shooting of that film, which apparently was a bit of a disaster. It was called Sex is Comedy, which wasn’t really that funny, but it was interesting. So I think you can work in different ways. Cassavetes worked very well with his wife, and a reparatory company is one way to go. Altman did that.

One of the interesting critiques of the concept of using real sex in film is that there’s a natural power imbalance between a director and the actors, and that sometimes an actor or actress will do things in a film that they don’t necessarily feel comfortable with because they want the part. Do you think spending that time together eliminates that power imbalance?

natural power imbalance between a director and the actors, and that sometimes an actor or actress will do things in a film that they don’t necessarily feel comfortable with because they want the part. Do you think spending that time together eliminates that power imbalance?

Mitchell: I think so. None of these people were professional actors, though. I kind of avoided the agents and the stars. They’re all artists in their own right – they do music and stuff. They’re also not exhibitionists; in the audition process it was very clear who was doing it for desperation or for exhibitionistic reasons or wanted to get off, and we avoided those people. I sought out people who were dancers and musicians and filmmakers and performance artists and they all wanted to be in it because they believed in its ethic, the idea of integrating sex back into the rest of your life. Philosophically we were all in the same boat, we had the same sensibility.

I also wanted to cast people who would be friends because we would be together for so long. A lot of directors forget that when casting – they think, ‘Let me cast this asshole to play the asshole and it’s going to be great because he’s an asshole!’ You have to live with him for months! What are you doing? That’s a very inexperienced, Hollywood way of thinking, or they’ve been watching Project Greenlight. So for me, we’re all buddies.

Some people did drop out, though. They weren’t quite in the group vibe, and it wasn’t to do with the sex because they weren’t characters who had sex. They dropped out because they weren’t team players and they wanted to work on their own projects, which is cool. It’s fine. The length of the process actually weeded out people who weren’t on the bus, so to speak.

Plus, one of the actors said, ‘If we have to do it so do you.’ I wasn’t interested in directing myself in anything anymore, but I jumped into one scene and did something I never did before – I ate pussy.

What was that experience like?

Mitchell: I’m eating a cheese sandwich as I talk to you.

It was better than craft service. That’s my standard line, but it’s true. It was quite delicious. I didn’t get aroused, though. I realized I could direct from that angle because I could see the actress’ face above me as I was eating her out, so I was multi-tasking. Plus I was texting.

Are we going to have to wait as long for the next one?

Mitchell: Probably, because I don’t do things that are easily financed. I have a children’s film I’m working on, but it might take a little while because I don’t like to just plug stars into pre-existing formulas. And I like to take time off.

But you’re not going to direct yourself again – does that mean you won’t act again?

Mitchell: I’m not into acting right now, but I think I will probably get back into it later. But not directing myself on film or stage, because it’s just too many hats. I didn’t direct the stage production of Hedwig, just the film, which I had to do. I had to also act in it, but I was more interested in directing.