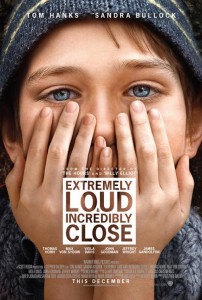

Nick Nunziata: Saddled with one of the most annoying titles of 2011 Stephen Daldry’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close is one of those higher stock high concept audience movies that attempt to straddle a very difficult line. When it works these kind of films are beloved. When it doesn’t, they are the worst kind of schmaltz imaginable. With Tom Hanks, Sandra Bullock, John Goodman, Viola Davis, and Jeffrey Wright supporting newcomer Thomas Horn and Daldry trying every trick in his toolbox, it almost comes together. Almost. Especially with the legendary Max Von Sydow showcasing his perennial magic as a mute and mysterious old man. With that said, as the movie is a manipulative tale about a boy trying to decipher a clue left behind by his 9/11’d father, there’s some treacherous terrain to traverse.

Nick Nunziata: Saddled with one of the most annoying titles of 2011 Stephen Daldry’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close is one of those higher stock high concept audience movies that attempt to straddle a very difficult line. When it works these kind of films are beloved. When it doesn’t, they are the worst kind of schmaltz imaginable. With Tom Hanks, Sandra Bullock, John Goodman, Viola Davis, and Jeffrey Wright supporting newcomer Thomas Horn and Daldry trying every trick in his toolbox, it almost comes together. Almost. Especially with the legendary Max Von Sydow showcasing his perennial magic as a mute and mysterious old man. With that said, as the movie is a manipulative tale about a boy trying to decipher a clue left behind by his 9/11’d father, there’s some treacherous terrain to traverse.

Renn Brown: There are a lot of warning signs right off the bat with this one… Hell, it’s tough to pick which one is more glaring. The magical leading kid with the powers of honed, poetic expression? The overwrought production design that leaves the heavy hand of professional Hollywood design smeared like a slug-trail of artifice over every object and place in the movie? Stunt-casting that shoves recognizable actors into small roles, many with some oh-so-clever affectation? The sheer volume of crying and emotional regurgitation? Any of these things can transform an otherwise sophisticated drama into cloying pablum, and in the case of Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close it’s to Daldry’s credit that none of these individual characteristics do so. As a whole they definitely lay bare the naked manipulation built into the core of the film though. Fortunately it’s not wrapped around the same kind of thin attempt at timeless, globe-trotting wisdom that Eric Roth has produced in the past with epic weepies like Forrest Gump and Benjamin Button, but it’s still pretty goddamn contrived. That it’s a slightly more grounded adventure revolving around a slightly more grounded character helps, but make no mistake: this flick is blatantly manufactured to jerk those tears and be “important.”

Nick Nunziata: I’m not going to argue that it’s not super manipulative. It is, even more so than some of the films you mentioned above. I mean, it’s about a kid whose dad flew out of the World Trade Center and his coping with the loss and finding meaning in it. There’s so much baggage on the premise that Delta charged it an extra $100. Add to that the fact that the leading character though creative and interesting, is oftentimes borderline insane. Early in the film in his narration he mentions that he may have Asperger’s and it’s never revisited. Spoiler: He has Asberger’s. So, though there are some really inspiring moments where this child’s sense of adventure keeps the film feeling magical there are also ones where the way he deals with his fears makes it very hard to stay in the story. The bottom line is that this is based on a novel and some of the things which work well on the page don’t translate to the screen as easily. But there is magic to this film. Considerable amounts of it, which is a Herculean achievement considering the blanket that anything related to 9/11 throws over media. The artifice that Renn mentioned worked a lot more with me because of how continual it was. This is a movie dripping with style, and though it’s often too much I found myself slowly falling into its graces.

Renn Brown: I think a larger problem with the film than its twee little magic protagonist might actually be in the nuts-and-bolts structure of the film. It’s a large and schizophrenic movie, not without admirable ambition, but it’s perpetually flitting back and forth between present narrative, flashbacks, emotional imagery, montages, and then the “quest” that is theoretically the center of the story, but is ultimately a minor part of what we see. Oskar Schell was raised on adventures and scavenger hunts engineered by his father to imbue him with a sense of adventure, curiosity, and sociability, thus it is natural that to process his father’s death he finds himself a new adventure. Looking for the backstory behind a key his father left behind, Oskar sets out on a quest that will take years to complete and requires him to meet hundreds of (inevitably quirky) people. While we do indeed meet some of these people, the actual act of going out and knocking on doors, hearing stories from various New Yorkers, and getting anywhere closer to the mystery’s answer is largely relegated to montage and often disappears for large stretches of time. There’s so much family drama and so many emotional outbursts to get through that the film has trouble maintaining a through-line with this set-up, and really it just becomes one of many ways the film chisels away at this boy’s emotional turmoil. That’s not necessarily a terrible thing, but it does give the film a start-stop-start quality that keeps the rhythm of the film from matching the slickness of everything on screen.

Nick Nunziata: I can see that, and there’s also the fact that there are no less than three Oscar magnets in the film and there’s only so much real estate to spread between them. Hanks comes off the most energetic and has the luck to be the one in the midst of the most traumatic moment in the film as he speaks into his family’s answering machine as burning jet fuel creeps towards him. That special Hanks energy adds so much to the film. He’s so easy to love and it’s refreshing to see that bounce and playfulness permeate his scenes with his son. It’s easy to forget what Tom Hanks is and how good he is at it. His moments help make a lot of the more arch moments later easier to swallow. Sandra Bullock doesn’t fare as well, both in the material she’s been given and the fact that this “dressed down” version of the actress they present is often distracting to look at. The big climactic moment for the actress hits the most hollow note in the story, because while we’ve just seen a minor literally risk his life for two hours his mother’s big reveal just comes off as easy. Viola Davis is good but given terribly little to do other than be divorced and sad about it. Luckily Thomas Horn is often excellent and Max Von Sydow, an actor who has been old longer than everyone else on Earth has been alive, does so very much without uttering even a single gasp.

Renn Brown: I’ve got no problem reiterating the kudos for Hanks and his effortless charm, as well as Max Von Sydow’s effortless old. Jeffrey Wright too comes in and classes up the joint as one of those brief but important encounters in the story. I’d even give more credit to Bullock for dissolving into a difficult role that is an amalgam of some of the rawest stuff in the film along with the most utterly unbelievable nonsense it tries to pull off. I’d also give director Stephen Daldry credit for somehow keeping all this precious kid stuff and 9/11 imagery on the rails without letting it descend too far into exploitation. The source material has gotten a lot of shit for being a cloying appropriation of a national tragedy for an unrealistic piece of hack fiction, which is a bit of a dangerous criticism, but that same feeling does hover over the film as well. It’s hard to shake the sense that still-raw feelings and imagery are doing a lot of the heavy lifting, rather than truly organic emotional catharsis. That said, our art should be fearless about processing these things (especially a decade later), so that’s a difficult line to draw.

Nick Nunziata: The end result is a well made if excessively designed mainstream attempt to create art for consumers who don’t like art. It works on the base level thanks to good performances and our own innate desires to connect with lost loved ones, and also as a showcase for the city of New York (which for a change gets to show some different facets than Hollywood usually offers). It’s pablum, but solid pablum.

Nick:

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Renn Brown: It’s definitely not as vaguely insulting or thematically worthless as some of Roth’s other high-concept character journeys, but the product is still too specifically polished to merit much of a pass. It’s well shot and well acted, but frankly the surgical quality to its attempt to ring the audience dry make it hard to take anything real from it. When something is so shamelessly built–top-to-bottom–to be an awards-seeking, wide-audience-pandering emotional event film, it ceases to provide any real cathartic value for what is still a real wound. Were the kid and his self-discovery less obviously a complete fabrication, then it might work on a pure character level, but that’s not the case. Once the strings calm down and the actors stop weeping all over each other and the tears among the popcorn kernels dry up, there’s nothing left that we’ve learned about ourselves or even one little, real-feeling human being.

Renn: Out of a Possible 5 Stars

Rating: