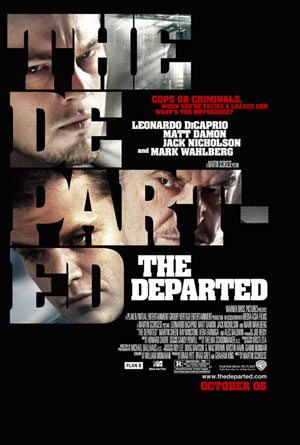

There are people who dismiss Martin Scorsese’s non-gangster films. Sometimes it feels like they don’t even acknowledge the existence of movies like or Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore or The Last Temptation of Christ or The Age of Innocence. These people are going to be more entrenched in their beliefs after the release of The Departed, Scorsese’s balls to the wall return to the world of crime. As much as I appreciate the films he has made over the last decade, there is no denying that The Departed is Scorsese’s best film since Goodfellas. It’s just a fucking awesome movie.

There are people who dismiss Martin Scorsese’s non-gangster films. Sometimes it feels like they don’t even acknowledge the existence of movies like or Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore or The Last Temptation of Christ or The Age of Innocence. These people are going to be more entrenched in their beliefs after the release of The Departed, Scorsese’s balls to the wall return to the world of crime. As much as I appreciate the films he has made over the last decade, there is no denying that The Departed is Scorsese’s best film since Goodfellas. It’s just a fucking awesome movie.

The Departed is based on the Hong Kong hit Infernal Affairs, and it is, plotwise, almost identical. But Scorsese has made his film exponentially better because he’s made it a real Scorsese film – sure, The Departed is filled with action and tension and sudden violence, but like all of Scorsese’s best films it’s populated with real, deep characters who do more than advance from one plot point to the other. And he’s set the action in a deeply detailed, fully realized world that’s as vibrant as the characters.

The basic plot is so simple and so strong it’s kind of amazing that no one thought of it before Infernal Affairs: The police insert a mole into the local branch of organized crime, and the crime boss does the same to the police. In this film it’s the Massachusetts State Police, and they pick young recruit Leonardo DiCaprio out to be the mole. His family has crime connections, and he’s got a hair-trigger temper. They drum him out of the police force and, to make it more plausible, throw him in jail. Meanwhile the mob chooses Matt Damon – from a very early age – to be their inside man. He excels in school and does great at the police academy. Soon he’s on the State Police fast track, moving up the ranks faster than they can print the citations.

At the center of these operations are the two fathers – Martin Sheen is the good father, in charge of the undercover operation. Jack Nicholson is the bad dad, the head of the crime family who also happens to be slowly losing what’s left of his marbles. As the two moles get closer to their new father figure, they become aware of each others’ existence, and the race is on between the moles to out their opposite number first.

This is the part of the review where I would usually call out one actor for exceptional work – this is very hard to do with The Departed because the cast works together so well, and without ego, and each and every one of them is working at the very top of their game. The plot of The Departed is a closely linked web, and the cast reflects that perfectly, almost without a single misstep.

The casting of Jack Nicholson caused some concern – he’s been playing increasingly zany versions of himself in his movies for years now, seemingly giving up actual acting (except for About Schmidt, which was made all the more notable by the fact that Nicholson actually bothered to adopt a persona). Technically The Departed doesn’t stray from that career path – his mob boss Frank Costello is very Jack. But there’s another level here in this man who (like Jack) has hit the heights of his career. He has all the money, all the coke, all the women. There’s nowhere else to go, except crazy. As the film progresses and as he becomes more and more obsessed with the mole in his midst, Costello becomes more and more violent – Nicholson plays one scene nonchalantly while covered in someone’s (we never learn whose) blood. Costello reminds me of Forest Whitaker’s Idi Amin, a roguish charmer who will turn on a dime and kill you where you stand. In one of the film’s best scenes, Costello interrogates DiCaprio about who might be the mole, and he pinballs back and forth between dripping sheer menace and being goofy and paternal. It’s unnerving.

DiCaprio has long been dogged by his early success and popularity, and continues to be haunted by his own baby-faced good looks. His collaborations with Martin Scorsese have obviously been partially about trying to advance to the next, adult level, and The Departed may be the film that does it for him. DiCaprio seems to channel his own anger at post-Titanic haters in this character, and when Scorsese gives him a trademark, Pesci-like sudden violence scene where he beats the shit out of two Italians harassing a local grocer, DiCaprio steps up to the plate and pummels the shit out of the ball. In a lot of ways his violence comes from the same place Pesci’s did, a reaction to seeming physically innocuous and weak. But for DiCaprio the violence also comes from the character, from the undercover stress he wears like a death shroud. To get close enough to Costello to be of any use, DiCaprio’s character must do increasingly terrible things, and it takes its toll.

Matt Damon’s character doesn’t have that problem. The movie is about the mirror relationship these two men have, and the best aspect of this is that while DiCaprio’s good cop must commit crime after crime, bloodying his hands, Damon’s undercover criminal sits back in comfort and success. DiCaprio shoots people and sells drugs for the public good while the bad guy only has to give information in coded phone calls.

With The Departed Damon further establishes himself as an honest to God fine actor – he’s magnetic in every scene and you find yourself rooting for him, even as he never lets you forget that he’s a scheming scumbag. What’s best is that he never has a moment of doubt, he never wonders whether or not he’s doing the right thing. Damon also has a baby face, but unlike DiCaprio his wide body and features telegraph a subtle menace. He works so well in the Bourne films because he looks so invisible while obviously maintaining the capacity to hurt you very badly. I feel like a lesser director would have swapped the roles, making Damon be the cop on the street up to his knees in human sewage and keeping DiCaprio behind a desk. But Scorsese is a master, and he understands that DiCaprio in the field feels vulnerable while Damon’s smile makes him the serpent in the garden.

Trapped between these men is Vera Farmiga as a police psychiatrist. The idea that she would end up involved with both moles is patently absurd, but the matter-of-fact presentation sells it. Farmiga herself also sells it, playing the role as a woman standing spanning the worlds of good and evil, but not quite sure which foot is in which world.

The Departed makes few missteps, but one of them is not giving Martin Sheen enough screentime. I imagine there was a draft somewhere in which Sheen’s Captain Queenan gets as much attention as Frank Costello. The casting of Nicholson skewed things, though, leaving Sheen much less time to make an impression as the light side of the movie’s great moral divide. He succeeds, no doubt helped by his own TV presidential baggage. And despite being teamed in many of his scenes with the completely spotlight stealing Mark Wahlberg as exquisitely foul-mouthed Dignan. Wahlberg has few scenes, and on paper serves mostly as a plot device, but on celluloid he’s an earthy street-brawler, the perfect counterpoint to Ray Winstone’s sadistic Mr. French (another fucking phenomenal performance – this character could sustain his own film, easily).

Michael Ballhaus, the DP on Goodfellas, is back with Scorsese here. His camera helps make The Departed feel like the natural successor to that film (moreso than the overly-coked up Casino), especially when combined with Scorsese’s sublime ear for rock songs on the soundtrack. He needledrops a very familiar Rolling Stones song right at the start of the film, giving The Departed an aural continuity, linking it to his history of classic gangster movies.

What sets The Departed apart, though, is the fact that this is the first Scorsese film about the cops – usually he just focuses on the robbers. He doesn’t quite have the feel for the law & order side of the equation, though – while the world of the gangsters enfolds you, the world of the cops – pretty much only represented by the glass-walled police station – is cold and distant. I think I would have preferred to see Scorsese tackle the cops as an extension of the crooks, as opposed to being their exact opposite. In the end that’s what we get from the DiCaprio and Damon conflict, anyway – the fine line between civilization and savagery, saint and sinner.

By the way, the fact that this conflict exists at all is nothing less than incredible. The two actors share almost no screen time and yet their scenes feel like they’re playing off of one another. Scorsese doesn’t excessively cut back and forth – each actor gets his own story comfortably told – but he intertwines the tales with clinical precision. DiCaprio and Damon are dynamite, and the excellence only escalates when they get together at the end in an all-too brief encounter.

Credit for that has to also go to William Monahan, who has taken Infernal Affairs’ clockwork plot and transposed it to his hometown of Boston. He has turned that fairly standard thriller into what is one of the wittiest cop movies ever – The Departed is very legitimately funny, and is going to end up on everyone’s list of most quotable movies of the young century.

The Departed is Scorsese’s best film in a decade. There’s no arguing this – the movie is filled with the kind of snap and sizzle that his best work contains, the kind of snap and sizzle so many have tried for but never replicated. But what does this say about Scorsese and his career? Does it say that, despite the constant protestations of myself and other Scorsese fanatics to the contrary, the guy really is at his best with crime films? Is it true that, despite a huge number of excellent films in other genres, Scorsese’s sensibilities work best when unleashed on a criminal milieu? Possibly – we’ll be able to take up this argument when his next film comes out, since The Departed proves more than anything else that this man is a director who is still at the top of his game, who can still deliver thrilling, engrossing entertainments that have depth and real meaning.