“Jonah Hex” Delivers His Own Brand of Justice in Accessible, Stand-Alone Stories

By Sean Fahey

Words can’t describe how happy I am that this series even exists, and the fact that it is so well executed makes it that much sweeter. I won’t hide my biases. I’m a huge fan of Westerns and I’ve always been a big fan of Jonah Hex as a character. (An ex-Confederate cavalry soldier turned bounty hunter, with half his face grotesquely scared. If that doesn’t spell badass, I don’t know what does.) That said, one of the elements I appreciate most about this series is its stand-alone story structure. Pick any issue up, any issue at all, and you’ll get a completely self contained story – a bitter dose of “justice” served up by the most feared (and morally complex) bounty hunter in the West. No need to buy four issues to get the whole story. No crossovers or tie-ins. One book, one story – and for that I tip my hat to series’ writers Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray. We need more books this accessible (and more Westerns).

Words can’t describe how happy I am that this series even exists, and the fact that it is so well executed makes it that much sweeter. I won’t hide my biases. I’m a huge fan of Westerns and I’ve always been a big fan of Jonah Hex as a character. (An ex-Confederate cavalry soldier turned bounty hunter, with half his face grotesquely scared. If that doesn’t spell badass, I don’t know what does.) That said, one of the elements I appreciate most about this series is its stand-alone story structure. Pick any issue up, any issue at all, and you’ll get a completely self contained story – a bitter dose of “justice” served up by the most feared (and morally complex) bounty hunter in the West. No need to buy four issues to get the whole story. No crossovers or tie-ins. One book, one story – and for that I tip my hat to series’ writers Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray. We need more books this accessible (and more Westerns).

Jonah Hex # 11, the latest issue in the series, also highlights another of my favorite qualities of the book – the fact that you never know exactly what you’re going to get. Granted, each issue focuses on Hex dealing out his own special brand of justice, but Palmiotti and Gray keep the series fresh by constantly mixing things up with the settings, supporting cast and tone of the stories. Last issue was a black as night “comedy” set in the backwater

Characteristic of the series, this issue explores the meaning of “justice” and how it is properly (and sometimes improperly) dealt out, and this more than anything else is what makes the series most intriguing. Here, El Diablo forces Hex to think long and hard about the ramifications and potential fallout of his bloodlust and whether it’s justified to begin with. That type of morally complexity is at the heart of any good Western tale, and Jonah Hex delivers on that front month in and month out.

RATING:

![]()

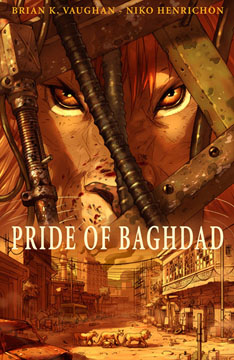

Pride of

(Vertigo)

By Jeb D.

Anthropomorphic animals have long been used to tell stories that allow characters to be “more human” than we “real” humans sometimes are, from Wind in the Willows to Watership Down. Such animals were once among the most popular characters in American comics—Disney’s are the best-known, of course, in the hands of genius creators like Carl Barks– and were as well respected as (say, rather, far better respected than) superhero comics. As the success of the spandex brigade (particularly the 60’s explosion of the “Marvel Age”) began to ghettoize other genres, the “funny animal” comic became specifically identified with reading for young children, and fell out of favor with “serious” readers. More and more of these comics became cheap knockoffs of Saturday morning cartoons or assembly-line animated movies, and the creation of them was handed over to anonymous pieceworkers. Over the past few years, as American comics has begun a slow recovery from their 90’s boom-and-bust, there has been room for a new generation of writers and artists to revive this once-flourishing genre, with everything from the samurai adventures of Stan Sakai’s Usagi Yojimbo to the picaresque adventures of the Mouse Guard to the post-modern ironies of Chris Ware’s Quimby the Rat.

Anthropomorphic animals have long been used to tell stories that allow characters to be “more human” than we “real” humans sometimes are, from Wind in the Willows to Watership Down. Such animals were once among the most popular characters in American comics—Disney’s are the best-known, of course, in the hands of genius creators like Carl Barks– and were as well respected as (say, rather, far better respected than) superhero comics. As the success of the spandex brigade (particularly the 60’s explosion of the “Marvel Age”) began to ghettoize other genres, the “funny animal” comic became specifically identified with reading for young children, and fell out of favor with “serious” readers. More and more of these comics became cheap knockoffs of Saturday morning cartoons or assembly-line animated movies, and the creation of them was handed over to anonymous pieceworkers. Over the past few years, as American comics has begun a slow recovery from their 90’s boom-and-bust, there has been room for a new generation of writers and artists to revive this once-flourishing genre, with everything from the samurai adventures of Stan Sakai’s Usagi Yojimbo to the picaresque adventures of the Mouse Guard to the post-modern ironies of Chris Ware’s Quimby the Rat.

By and large, though, even the best work in this field has been relegated to a ghetto of its own—often a plush and comfortable one, with great reviews and respectable sales, but comics without a humanoid protagonist have tended to be the work of new and/or independent artists, who are too easily “typecast”, and too often overlooked by readers of more “adult” books (superheroes or otherwise). What’s been needed to change that perception is to have a comic creator who’s made his name in more conventional comics work take up the challenge of telling a compelling story through non-human eyes. Now it’s happened, and I honestly don’t think I exaggerate when I say that American comics may never be quite the same again.

Bryan K. Vaughan is one of the most versatile writers working in comics today. His Y: The Last Man is a dystopian sci-fi mystery that appeals to readers outside the regular comics audience; Ex Machina shows how effectively the concepts of superhero storytelling can be integrated with the contemporary story of social conscience; and his Runaways series just about retires the field for teen superheroes. Certainly, if anyone was to stretch himself into an area neglected by the core comics readership, it wouldn’t have been hard to predict that he’d be the guy. What might have been impossible to predict would be what a staggering success he’d make of it. His newest work, Pride of Baghdad, is the best original graphic novel I have read since… hell, I don’t know—Black Hole and Epileptic might the only recent points of comparison.

The story was “ripped from the headlines”: in 2003, a bombing raid destroyed portions of a zoo in

I don’t want to spoil any more of the story for you—just let me say that it’s gripping, heart-rending, moving, and thought-provoking beyond anything that American comics have produced in ages. You’ll read it in one sitting, and regret that it wasn’t longer.

Artist Niko Henrichon (best known for the “Barnum!” graphic novel) gives the book a stunning landscape, a sort of blasted savannah in the midst of the devastated city. The character design is convincing, but not “over-realistic”: there’s a hint of Disney’s Simba in young Ali, and the adult lions look just “cartoony” enough to allow us to imbue them with the all-too-human characteristics Vaughan gives them without being distracted by the unreality of the situation.

When I said this book might represent a turning point for American comics, I wasn’t exaggerating (much): this graphic novel has the potential to breakout to audiences far beyond such crossover hits as Sin City or Civil War. The only parallel I can think of is Jeff Smith’s Bone: Pride of Baghdad is a book that readers of any age can savor, and, by comparison, its brevity and grounding in our real world make it even more direct and appealing. It should become a fixture on bookstore shelves everywhere, and a fine introduction to the delights that graphic storytelling has to offer.

You won’t read a better comic this year.

The Psycho

(Image Comics)

By Graig Kent

James D. Hudnall and Dan Brereton’s The Psycho was first printed by DC Comics fifteen years ago, and retains the distinction of being DC’s first creator owned property, in part paving the way for the Vertigo line which feeds off similar arrangement. As three-issue, prestige format mini-series produced in the era of Marvel’s huge X-Men revamp, it was an expensive and decidedly different alternative to mutants-galore, and though it didn’t lack success, benchmarking it against the sales of Clairmont and Lee’s X-Men in determining the title’s future didn’t do the book any favors.

James D. Hudnall and Dan Brereton’s The Psycho was first printed by DC Comics fifteen years ago, and retains the distinction of being DC’s first creator owned property, in part paving the way for the Vertigo line which feeds off similar arrangement. As three-issue, prestige format mini-series produced in the era of Marvel’s huge X-Men revamp, it was an expensive and decidedly different alternative to mutants-galore, and though it didn’t lack success, benchmarking it against the sales of Clairmont and Lee’s X-Men in determining the title’s future didn’t do the book any favors.

A lot has changed in fifteen years, in terms of what’s popular, what constitutes good sales, and also what’s considered good reading. A lot of The Psycho’s 1991 contemporaries, including the bulk of those titles which outsold it, don’t hold up well. Whether the art now looks dated or the writing isn’t as palatable by today’s standards, or just set in an era that is passé or irrelevant, not a lot of those comics have much lasting power. Yet, here’s the Psycho, reprinted in a gorgeous trade collection from Image Comics, a book that over a decade and a half later still feels fresh, exciting and relevant.

The story is set in an alternative history, where instead of the atomic bomb, the U.S. developed a serum for creating superhumans, and thus remapping the decades that followed. In the setting of the Psycho, governments have routinely been toppled by black ops teams of Freelance Costumed Operatives (aka F.C.O.s, aka Psychos), and nations are striving to amass their own armies of these mercenaries. Jake Riley is a

While complete in itself, there isn’t really a finale to the story. It’s like watching (or reading) Fellowship of the Ring without having the rest of the story available: there’s definitely a beginning, middle and end, but it’s also just a part of a bigger whole. There’s currently no sequel to The Psycho, but it has long been on the slate for film adaptation. Hudnall’s story takes a curious look at espionage and inter-government affairs, while also dishing out intense “Bourne Identity with super-powers” action. Dan Brereton’s art is as much a draw as the well-executed concept. Done early in Brereton’s career, it’s a highly impressive and distinctive inauguration, showcasing his trademark style from the onset and holding up nicely against his later works. The trade collection also features some of Brereton’s sketchbook pages and conceptual work for the series. A great read overall, which, had it been printed years later, would likely have been a successful ongoing..

RATING:

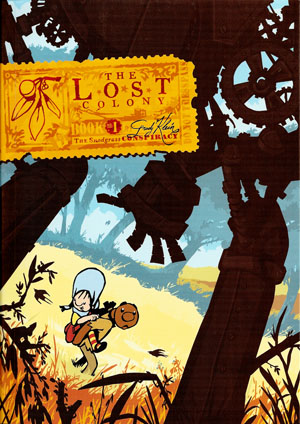

The Lost Colony: Book 1 – The Snodgrass Conspiracy

(First Second Books)

By Graig Kent

Contemporary education has taught us that slavery is wrong, and that its place in (North) American history is in some respects embarrassing and/or infuriating (depending on your ancestral viewpoint). In any case it’s a sensitive subject, and as such it doesn’t always make for the most enjoyable of entertainment. So when a book like The Lost Colony comes along set in nineteenth century America where rarely was a person of color free or not oppressed, and tells its story with a sense of whimsy, well, it’s kind of uncomfortable.

Contemporary education has taught us that slavery is wrong, and that its place in (North) American history is in some respects embarrassing and/or infuriating (depending on your ancestral viewpoint). In any case it’s a sensitive subject, and as such it doesn’t always make for the most enjoyable of entertainment. So when a book like The Lost Colony comes along set in nineteenth century America where rarely was a person of color free or not oppressed, and tells its story with a sense of whimsy, well, it’s kind of uncomfortable.

This is the first in an expected series of books by Grady Klein, set on an unmapped island where its multitude of eccentric multicultural citizens live in a state of discord while at the same time having a proud sense of community and self-preservation. There are no token characters here, and though stereotypes are used, they’re also exploited by the characters rather than used as a characterization crutch. The scenario for “The Snodgrass Conspiracy” finds a stranger on the island putting up posters for a slave sale on the mainland. The sudden appearance of someone in their sheltered-if-not-exactly-quiet community, not to mention his reason for being there, has all the locals in a tizzy, each for their own reasons, and a bizarre comedy-of-errors unfolds from there as the different residents conspire and scheme.

With a background in animation, Klein’s artistic skills shine through in his vibrant and attractive cartooning, simplistic but rich in texture and depth. He has developed clearly cut and distinctive visual personas to match each of the colorful cast of characters that populate his book, at the same time goofy and endearing. As a newcomer to comics, Klein’s storytelling is challenging at first, as he likes to visualize character’s inner thoughts (much like Scrubs or That 70’s Show quick-cut asides), as well as a plethora of reaction shorts or blank pauses, all of which busies up the page. This can be distracting or confusing but as the book progresses it does begin feel more natural.

With The Lost Colony Klein never deals with race or slavery as an issue head-on, which isn’t to say that he ignores it either – incorporating elements into his story, in fact – but rather he has developed a story and characters that take place in a time when the issues weren’t dealt with as we deal with them today. The purpose of the book isn’t to highlight the struggles of the era, which is what most stories set in that time do (or else they ignore it altogether) but rather relate a often silly slapstick ignoring much politicizing or preaching. Klein’s book doesn’t sets out to offend, taking great care in making sure that no one character is mere stereotype, instead, Klein sets out to tell a fun, slightly fantastical story which just happens to take place in a time frame many aren’t that comfortable with. It’s a fascinating and indeed fun read, even if it’s not an easy one to relax into.

RATING:

Shatter

(

By Elgin Carver

Computer geeks will argue Mac versus

Computer geeks will argue Mac versus

Those last two attributes still show through today. In this compilation, a private eye/bounty hunter from the future meets the type of people and situations that might be expected from such a person in such a time and place. It is a reasonably original, fast paced and satisfactorily complicated story, even if reminiscent of Blade Runner and Soylent Green. The images, restricted by the size of the pixels, are somewhat distracting at first but become almost hypnotic. When one considers what restrictions these two men operated under, it is a tremendous achievement. Artists who do all they can within limitations imposed from the outside are to be admired.

Few people read this the first time through, and the initial impressions a quick flip of the pages will give may keep everyday readers away this time but this deserves a better fate. If you see a copy pick it up. This book is not just a historical artifact of sorts, it is a demonstration that writing carries the story forward, and talented artists can make more from their materials than most could imagine.

RATING:

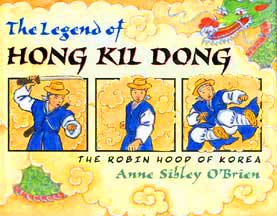

The Legend Of Hong Kil Dong: The Robin Hood Of Korea

(Charlesbridge)

By Elgin Carver

Sixty years ago comics were over fifty pages long, printed on very cheap paper, and cost a dime. Their soft covers were stapled together and were a standard size, taller than wide. As the years passed they lost pages and the price rose over and over again. As the size of the books reached about 30 pages the paper improved and the prices rose even more quickly. More and more pages became full page ads. As the value dropped and the cost rose, the number of readers fell, and the future of the medium seemed grim indeed. When the handwriting on the wall became so plain that even the bean-counters could read it, some experimentation was instituted to expand the market. Today the graphic novel can be found in most bookstores and the sizes, cover styles, and shape variation proliferate. The number of comic book enthusiasts remains low. Most of these changes have been aimed at established, older fans. Where is the future of comics?

Sixty years ago comics were over fifty pages long, printed on very cheap paper, and cost a dime. Their soft covers were stapled together and were a standard size, taller than wide. As the years passed they lost pages and the price rose over and over again. As the size of the books reached about 30 pages the paper improved and the prices rose even more quickly. More and more pages became full page ads. As the value dropped and the cost rose, the number of readers fell, and the future of the medium seemed grim indeed. When the handwriting on the wall became so plain that even the bean-counters could read it, some experimentation was instituted to expand the market. Today the graphic novel can be found in most bookstores and the sizes, cover styles, and shape variation proliferate. The number of comic book enthusiasts remains low. Most of these changes have been aimed at established, older fans. Where is the future of comics?

The future is where it is for all products. The younger generation. Some small compilations of Archie comics and television cartoon shows are placed in a few locations that once were fertile fields for the growth of new readers- grocery and drug stores. Little else is readily apparent. Anne Sibley O’Brien has created what appears at first glance to be a typical children’s hard back storybook. On the inside, however, are relatively typical children’s book illustrations in comic book form about the legend of a Korean youth who through the use of his physical and spiritual gifts, and his ability to use magic, helps the peasants of his time to a better life.

Portions of the story are a little tough for adults to accept, but doubtless an age appropriate audience will find it intriguing. The artwork is competent, although the color is a little weak. What is most exciting is the use of the comic book genre expanded into the storybook field. This would be an excellent gift for a niece, grandchild, or best friend’s son. They would love to read along or, if old enough, on their own. After that, they might like to take a trip to the local comic book store. Marvel and DC would accomplish more by giving this book away on Free Comic Book Day to new fans rather than copies of their own books to the established market.

RATING:

![]()

Captain America #21 (Marvel)- In the wake of his recent Harvey Award as this year’s top comics writer, let’s check in as Ed Brubaker wraps up the latest Captain America story arc with a bang. It’s all here: the Red Skull, an awakened Sleeper, Crossbones, Bucky, Master Man, Sharon Carter—as well as demonstrating a nice touch with British superheroes Union Jack and Spitfire. Artist Steve Epting brings all the blood and thunder we could ask form, but can still show us the agony on Cap’s face as he sees Bucky once more headed for death trying to stop the Skull’s latest monstrous creation. And late in the story there is either an odd editorial oversight, or a jump-cut that’s a clue to a major new development. Personally, I can’t wait to see which – Jeb D.

Captain America #21 (Marvel)- In the wake of his recent Harvey Award as this year’s top comics writer, let’s check in as Ed Brubaker wraps up the latest Captain America story arc with a bang. It’s all here: the Red Skull, an awakened Sleeper, Crossbones, Bucky, Master Man, Sharon Carter—as well as demonstrating a nice touch with British superheroes Union Jack and Spitfire. Artist Steve Epting brings all the blood and thunder we could ask form, but can still show us the agony on Cap’s face as he sees Bucky once more headed for death trying to stop the Skull’s latest monstrous creation. And late in the story there is either an odd editorial oversight, or a jump-cut that’s a clue to a major new development. Personally, I can’t wait to see which – Jeb D.

RATING:

Essential Hulk Vol. 4 (Marvel) – The continuing expansion of the "phone books" collection by both Marvel and DC should be a sign of joy for everyone without complete runs. Here a gaggle of Marvel’s writers churned out classic story after story. Roy Thomas, Archie Goodwin, Steve Englehart, Steve Gerber, and Dick Ayers each plotted and scripted stories that are not deep with the psychological life of Bruce Banner but are rich with plenty of "Hulk Smash," which is, after all, why Hulk was created. Herb Trimpe penciled most of the 23 issues reproduced here in black and white. In half of the stories John Severin’s inks combine to create the most classic look of any period of the Hulk’s checkered past, while Sal Trapani and Jack Abal picked up the slack for the rest. This is a truly fun read for a very reasonable cost. –Elgin

Essential Hulk Vol. 4 (Marvel) – The continuing expansion of the "phone books" collection by both Marvel and DC should be a sign of joy for everyone without complete runs. Here a gaggle of Marvel’s writers churned out classic story after story. Roy Thomas, Archie Goodwin, Steve Englehart, Steve Gerber, and Dick Ayers each plotted and scripted stories that are not deep with the psychological life of Bruce Banner but are rich with plenty of "Hulk Smash," which is, after all, why Hulk was created. Herb Trimpe penciled most of the 23 issues reproduced here in black and white. In half of the stories John Severin’s inks combine to create the most classic look of any period of the Hulk’s checkered past, while Sal Trapani and Jack Abal picked up the slack for the rest. This is a truly fun read for a very reasonable cost. –Elgin

RATING:

Battler Britton # 3 (DC Comics) – I’m a World War II history buff. But I’ve always found the air war – even the Battle of Britain – the least interesting aspect of that conflict, probably because it’s so mechanical and tech based. But that’s the power of writer Garth Ennis, he brings the human element out – and Battler Britton is a character heavy story about the tensions and anxieties of Allied pilots in North Africa during one of the most critical points of the War. The real conflict here is not so much between the Allies and the Germans, but between the Americans and British pilots who are forced into a joint command for the first time. Different cultures. Different levels of experience. Different opinions on tactics. They all clash, and the real struggle for Battler, the British Wing Commander in charge of the joint operation, is to get the problems on the ground resolved and mold a unit cohesive enough to ensure success in the skies. Not wholly original, granted, but incredibly well executed nevertheless. Add to that the breathtaking artwork of Colin Wilson, and Battler Britton is one of the more exciting and visually stunning series currently on the racks. (Note to DC – More war comics damn it!) – Sean

Battler Britton # 3 (DC Comics) – I’m a World War II history buff. But I’ve always found the air war – even the Battle of Britain – the least interesting aspect of that conflict, probably because it’s so mechanical and tech based. But that’s the power of writer Garth Ennis, he brings the human element out – and Battler Britton is a character heavy story about the tensions and anxieties of Allied pilots in North Africa during one of the most critical points of the War. The real conflict here is not so much between the Allies and the Germans, but between the Americans and British pilots who are forced into a joint command for the first time. Different cultures. Different levels of experience. Different opinions on tactics. They all clash, and the real struggle for Battler, the British Wing Commander in charge of the joint operation, is to get the problems on the ground resolved and mold a unit cohesive enough to ensure success in the skies. Not wholly original, granted, but incredibly well executed nevertheless. Add to that the breathtaking artwork of Colin Wilson, and Battler Britton is one of the more exciting and visually stunning series currently on the racks. (Note to DC – More war comics damn it!) – Sean

Ms. Marvel #7 (Marvel) – I’m still not entirely sure that anyone at Marvel knows what the plan for this book is (if they do, they’re keeping it to themselves). It began as sort of an attempt to make Carol (Ms Marvel) Danvers into Wonder Woman by way of Jessica Jones, they then threw in a space adventure followed by a mystical showdown, then tossed Ms. M into the Civil War. Now, at the height of that conflict, we’re suddenly getting an assortment of C-list Marvel characters (Shroud, Arana, Wonder Man, Arachne) in a sprightly chase story that’s half strained dialogue and half wild action. Bendis protégée Brian Reed keeps the characterization diverting and artist Roberto De La Torre may still have the occasional weakness in basic anatomy, but he sure knows how to panel an action scene. I have to admit that I’m drawn toward the book’s quirkiness (though I confess it might just be that I’m going to keep reading till I think I have a handle on it), and after the dust of Civil War settles I’m sort of hoping this book can stay out on the periphery, and be a place for those half-forgotten denizens of the Marvel Universe to guest star and have their moments.– Jeb D.

Ms. Marvel #7 (Marvel) – I’m still not entirely sure that anyone at Marvel knows what the plan for this book is (if they do, they’re keeping it to themselves). It began as sort of an attempt to make Carol (Ms Marvel) Danvers into Wonder Woman by way of Jessica Jones, they then threw in a space adventure followed by a mystical showdown, then tossed Ms. M into the Civil War. Now, at the height of that conflict, we’re suddenly getting an assortment of C-list Marvel characters (Shroud, Arana, Wonder Man, Arachne) in a sprightly chase story that’s half strained dialogue and half wild action. Bendis protégée Brian Reed keeps the characterization diverting and artist Roberto De La Torre may still have the occasional weakness in basic anatomy, but he sure knows how to panel an action scene. I have to admit that I’m drawn toward the book’s quirkiness (though I confess it might just be that I’m going to keep reading till I think I have a handle on it), and after the dust of Civil War settles I’m sort of hoping this book can stay out on the periphery, and be a place for those half-forgotten denizens of the Marvel Universe to guest star and have their moments.– Jeb D.

RATING:

Phonogram #2 (Image Comics) – For a time comics were often referred to as “comics magazine”, which I believe was a concerted effort on the part of industry folks to try and make the format seem more mature. It strikes me though that most comics have little in common with magazines, which typically offer a multitude of articles and diverse, if quick and disposable, reading material. Phonogram is one of the few books that actually feels like a comics magazine, featuring a hefty back quarter full of articles, creator notes, a glossary of terms and a letters page. I actually found myself reading this part first. Not that the story – in which the protagonist leads the reader deeper into the world of music-based magic – is disposable or ancillary. Despite the fact that this issue seems to be distracted from the greater arc as introduced in issue one, Gillen and McKelvie continue to impress in both story and art. The “Constantine: Rock Journalist” feel hasn’t departed and it’s engaging even if you aren’t brushed up on your Brit-pop. Now one of my most anticipated books every month. –Graig–

Phonogram #2 (Image Comics) – For a time comics were often referred to as “comics magazine”, which I believe was a concerted effort on the part of industry folks to try and make the format seem more mature. It strikes me though that most comics have little in common with magazines, which typically offer a multitude of articles and diverse, if quick and disposable, reading material. Phonogram is one of the few books that actually feels like a comics magazine, featuring a hefty back quarter full of articles, creator notes, a glossary of terms and a letters page. I actually found myself reading this part first. Not that the story – in which the protagonist leads the reader deeper into the world of music-based magic – is disposable or ancillary. Despite the fact that this issue seems to be distracted from the greater arc as introduced in issue one, Gillen and McKelvie continue to impress in both story and art. The “Constantine: Rock Journalist” feel hasn’t departed and it’s engaging even if you aren’t brushed up on your Brit-pop. Now one of my most anticipated books every month. –Graig–