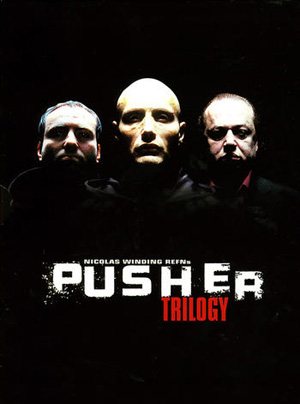

Nicolas

Nicolas

Winding Refn isn’t a household name, and probably never will be. You don’t find mainstream fame by making uncompromising crime films that are both phsyically and emotionally brutal.

His movies Bleeder and Fear X (with

John Turturro, co-written by Hubert Selby Jr) got some attention outside his

native Denmark and surrounding Europe. Ironically, it’s Pusher, his 1996 debut,

that will be his gateway into a more widespread awareness a decade later.

Pusher started off as one of the

innumerable mid-’90s crime flicks floating in the wake of Tarantino. But even

as the film proceeds, you can see Refn changing his mind about what he wanted out

of the gangster film. In 2004, when he made his unlikely return to the criminal streets of Copenhagen, his ideas had coalesced even further. The unexpected sequels Pusher II: With Blood On My Hands and III: I Am The Angel of Death represent a bleak

refusal to be suckered into a gangster mythology.

That

doesn’t mean they’re not fun, though. In fact, the ugly and realistic attitude

of the trilogy makes the light moments in each film feel hard won and more

memorable than the easy comedy of Snatch and its ilk.

I’d seen Fear

X a while back, but Refn’s name didn’t resonate when I read the page

about the Pusher films last year at the Toronto Film Festival. Seeing Pusher

3 – the most graphic and darkly funny of the trilogy – was enough to

etch his name. I jumped at the chance to see all three films screened back to

back on the last day of the festival. The trilogy turned out high on my list of

favorites, and I was thrilled when Magnolia picked them up for distribution in

North America.

So I was

equally happy when Devin’s trip to San Diego took him out of commission for the

NYC roundtable with Refn. I got a few minutes on the phone with the director to

discuss the three films and the future of his career.

The Pusher Trilogy officially opens in New York City on Friday the 18th. It will roll out

to LA in November and other markets afterward. CHUD’s review of the films will

run tomorrow.

a decade, why did you go back to Pusher and this subject matter?

It’s a

very simple answer: I owed a million dollars. That’s it. I was in such huge

debt. To get out of it very quickly so it didn’t haunt the rest of my life I

needed to come up with something I could easily finance that I knew had an

international appeal. So I forced myself to go back to the first one —

something I always vowed never to do. But I think my refusal also came out of

being afraid of not being able to do it better than the first. When you have to

go back to something you did ten years ago…but it became a very good experience

and has probably made me a better filmmaker.

Why

would you say that?

I think

that it forced me to understand that film is a commodity, that you have to look

at it as a business, and that sometimes you have to let go of your pure

artistic integrity and combine the two things — business and integrity — into

it’s own artform, rather than only concentrate on one or the other.

The

new films feel very genuine, not as if they’re simply commodities.

Good. In

a way, you can say that the first one, which I made at 24, came out of me being

a gangster film fan. I was a fan of the genre. So it came out of my liking for

that. But halfway through shooting it, I realized that what I was really

interested in was not crime and that world and lifestyle, but the

vulnerabilities of people. And I have to say that Pusher is

almost two films, because it takes a radical turn, and becomes more about

Frank’s emotional downfall, whereas the first half is very action-oriented. So

when I went back to it for 2 and 3 I very much concentrated on social issues of

making films about people in the criminal environment, rather than simply

making movies about crime. I don’t think the world needs any more of that.

It’s

easy to categorize these films as the European Godfather trilogy, but they do

even less to glorify or advocate that lifestyle.

That was

very important to me. I have children, and I’m saddened sometimes at how the

media can package a certain type of life because it can sell. It’s false. When

I made 2 and 3, and had a lot of real gangsters playing in the films, I

cemented my belief in that. These people all had a sadness. This was not a life

that was ideal for anyone. It was a life they fell into.

In

casting and working with criminals, did you see a growing self-awareness in

them as the films progressed?

The

people I was working with were ones that already had that self-awareness, I

think, and could look at their lives from outside, or with a different point of

view. But again, these films weren’t made to judge them. They weren’t made to

judge anybody, and I don’t make moral films. I’m not trying to push an agenda

down anyone’s throats. They’re made much more in the sensibility of a voyeur,

using the camera as an eye.

Did

you write both at once?

Oh, yes.

I was so pressured for money, and I think I wrote Pusher 2 in

like two weeks, maybe a month. And then a week to do Pusher 3…I

was so desperate.

Despite

that fast gestation, there’s a real distinction between the films, which

carries over visually as well.

I think

it’s very much about the characters. The trilogy was very much conceived as a

television concept, with the criminal world as a background. That’s the

environment, but it’s very closed, and there are these people moving within it,

and it becomes very episodic storytelling. What was very important to me was

that each story was different from the others. Pusher was about a

man who realizes he’s not capable of showing his emotions, and that becomes his

downfall. Pusher 2 is a man who longed for his father’s

attention, and realizes he has to kill him. Pusher 3 is a king

who’s losing his empire, and his attempt to regain it at the expense of his

humanity.

The

end of Pusher 3 is quite apocalyptic.

That was

very important to me at that point. In the first film, the characters very much

had a kind of ‘live fast, die young’ attitude, which plays into the

glorification that I find so ridiculous. So for me, part 3 was very important

to cement that this is the complete opposite of what is usually sold by the

media about crime. And I believe that as a filmmaker, I do have a moral

obligation…without specifically trying to drive a message. When you do that, it

just becomes a political element. And what art can do that politicians can’t is

inspire people to think.

One

thing that stands out in the third film is the mix of languages and cultures. I

love that the characters don’t understand each other, and that there’s a clash

between them not only personally, but culturally.

I think

that in

becoming globalized, and since I grew up in

nationalities, I have a very globalized view of the world. But

country. Even though we want to be globalized, we’re definitely not ready for

it. We’re really very bad at incorporating immigrants into our society. We want

them to be like us. We never say ‘we’, we say ‘them’ or ‘us’.

We’re going

through a version of that in the States, as well.

We see

that, and in Scandanavian countries we have a long history of it. So I really

wanted to show

is, even though the official take is very different. It made it difficult to

finance, because from a commercial standpoint, making a movie about foreigners

in

Especially if the characters don’t speak Danish. So when I wrote the script, I

wrote all the dialogue in Danish, and marked lines with very small letters to

show the dialect they’d really be speaking. And none of the financiers noticed

that! So it wasn’t until they saw the finished film that they had the shock

that these characters are speaking their own languages!

In

including other nationalities and making them all criminals.

I think

in

correctness, which is a very dangerous thing. It’s really suppressed a lot of

emotions in my country. The socialist government we have in power for many

years, political correctness became such a force that people couldn’t voice

anything that might be negative or questioning without it being labeled as a

racist or nationalistic statement. It becomes something that no one will touch

upon, and then it explodes. And when that happened, it gave the right-wing

movement all over

Is

that changing in

No,

unfortunately our government is now even worse.

By

making these movies, have you escaped your debt?

I paid my

debt, which is good. Then I realized I had to sue my ex-lawyers, which is a

whole other situation! The Corporation, part 2.

What

are you doing now?

Well, I

like to do things very differently from one to the next. Pusher 1 to

Bleeder to Fear X…the next thing I’ll do is another

American film called Valhalla Rising, about the Vikings

discovering

That

could be an undertaking. What scale are you working towards?

Here’s

what I’ve learned. To survive in the film industry you have to learn two things,

writing and distribution. To make films in the industry, you have to learn two

things: make a good film, and make it cheap. That’s my take on everything. I

always say ‘less is more’.

All

three Pusher films have a dedication. Can you explain them?

Every one

of my films is dedicated to someone in my life that has been part of something

in me, especially Pusher 2. The first is dedicated to my uncle. The

second is dedicated to Mr. Selby, and I miss him every day. He helped me make Fear

X, which was a very troubled, but very fruitful experience for me. And Pusher

3 is dedicated to a Danish director named Poul Nyrup, who made these

very odd kind of exploitation films in the ’60s. He used people from the

streets to make youth films with rockabilly music. He was scolded and laughed

at and you can’t even find his negatives any more. And they were terrific! They

played all over the world, but in

was so sad when I learned his negatives were lost that I wanted to give him

some lasting respect.