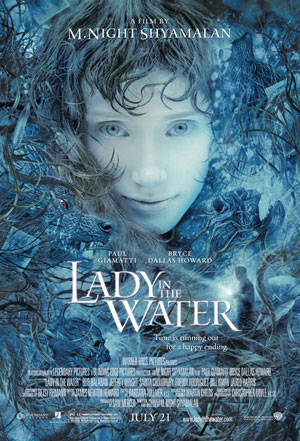

M. Night

M. Night

Shyamalan calls Lady In The Water a bedtime story, but I suspect

he wouldn’t know a fairy tale if it pissed on The Village. Granted,

somewhere at the bottom of this murky and repulsive water lurks the kernel of a

unique tale. But watching this film is like having Shyamalan punch you in the

gut before diving to find it.

Lady

In The Water is

a tale about stories — the Lady herself is even named Story — but more to the

point, it’s about how people really need to believe in and understand the value

of stories. Particularly if they’re told by Shyamalan. To make that loud and

clear he includes not only a smug film critic, but himself, portraying a man

destined to change the world. And that’s only part of what’s wrong with the film.

Paul

Giamatti, affecting and honest as ever, is Cleveland Heep, presumably named

after the locale of Giamatti’s breakthrough film, American Splendor.

(More on that in a moment.)

dislocated apartment complex. As frequently is the case with ugly apartment

blocks, this one is built around a swimming pool. In the pool is Story.

Story is

a Narf. We’re told that Narfs are sea nymphs with the power to inspire mankind.

In this case, the Narf is meant to inspire an individual, who will then

transform mankind. She’s hounded by a wolf-like beast called a Scrunt, and will

be retrieved by a giant eagle after performing her task. There’s also a

triumvirate of sorta evil monkey guys, but you won’t see much of them.

Value

those details. I gave valuable hours (two) and brain cells (countless) to

gather them. For this movie, Shyamalan tosses out the first rule of storytelling:

simplicity. Or elegance, I forget which one is actually the first rule. This

film has neither. The history and purpose of Narfs are explained through dreary

exposition, one scene after the other, relying on a Korean mother and daughter

perhaps borrowed from the Asian remake of a Telemundo soap opera shooting next

door.

The

Korean family is but two of many horrible characters inhabiting

stoners, the friendly Latin family with five shrill daughters, the Lady Who

Likes Animals. (Hopefully not this film’s sequel.) And I wanted to cry every

time Sarita Choudhury, as Shyamalan’s sister, opened her mouth to say yet

another thing that wasn’t funny. Remove Cleveland and his nymph, and you’ve got

a cast of characters UPN would never have allowed to sully even a pilot.

At first

I was completely put off by the insipid characterizations swirling around Cleveland

Heep. Then I realized that Shyamalan had mistaken stereotype for archetype. That

mistake, not the silly film critic, is one of many shots that sinks

In The Water.

this story unfold is the worst time I’ve had at the movies this year. There’s an

attempted level of meta-commentary, presumably about filmmaking and

storytelling, but Shyamalan is no Charlie Kaufman. By focusing on these film

school caricatures, he often forgets all about the bedtime story supposedly at

hand and can barely get any meta context together. Crucially, there is no

wonder, no joy, and no thrill at Story and the creatures that oppose her.

All we

get is a bunch of humans gamely trying to make it to the end of the movie. Their

place in the story is obvious from the beginning, so there’s nothing for us to

figure out. We wait until

together, by which time the possibility of any reward for us has escaped.

Not only

does Shyamalan treat these paper-thin and frequently shrill people as if they

were interesting, he literally casts some of their words as gospel. It’s one

thing to watch a bad story unfold in a halting, disaffecting manner. It’s

entirely another to be told over and over that it’s all terribly important. And

when one of the most important characters is portrayed by a flat, unlikable

presence (M Night Shyamalan) it gets even worse.

And with

that, Shyamalan has outdone his own self-indulgence. For while Bob Balaban’s

out of touch critic provides most of the movie’s lightest moments, Shyamalan can’t

let the movie go without promoting himself. Not only is Balaban a mouthpiece

for Shyamalan’s dismissal of critics, which gets in the story’s way every time,

the director himself is around to prove that his stuff really IS worthwhile. So

what is Lady In The Water really about? Stories and their value,

or critics and their lack thereof? I know which one I pick.

Oh,

right. That bit about American Splendor. That’s a movie that

achieved significantly wider notice due to critical approval. Without

unanimously glowing reviews, would the public have ever glanced at Harvey

Pekar? Unlikely. And yet in a film so determined to ignore and even destroy

critics, even at the expense of it’s own story, we’re continually reminded of

their better efforts. Thanks for the laugh, Night. It’s unintentional, I’m

sure.

2 out of 10