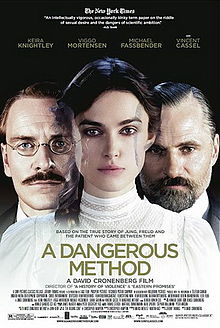

Sex. If there had been any lingering questions about what aspect of his films Canadian cinemaniac David Cronenberg is most creatively drawn to, I think A Dangerous Method answers that. It’s the sex. I knew next to nothing about A Dangerous Method going into it. I knew it was adapted for the screen by Oscar-nominated writer Christopher Hampton (Atonement) from his own 2002 stage play that I also knew nothing about, The Talking Cure, itself based on John Kerr’s 1993 non-fiction book, A Most Dangerous Method — from which the film wisely nabbed its title. I knew it was about Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, with Viggo Mortensen and Michael Fassbender playing the respective roles. That was about it.

Sex. If there had been any lingering questions about what aspect of his films Canadian cinemaniac David Cronenberg is most creatively drawn to, I think A Dangerous Method answers that. It’s the sex. I knew next to nothing about A Dangerous Method going into it. I knew it was adapted for the screen by Oscar-nominated writer Christopher Hampton (Atonement) from his own 2002 stage play that I also knew nothing about, The Talking Cure, itself based on John Kerr’s 1993 non-fiction book, A Most Dangerous Method — from which the film wisely nabbed its title. I knew it was about Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, with Viggo Mortensen and Michael Fassbender playing the respective roles. That was about it.

As a Cronenberg fan, having seen all but one of his theatrical films, I had a hard time imagining what a David Cronenberg film about Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung was going to be. Cronenberg doesn’t seem the type to go in for a Pride and Prejudice and Zombies style historical fantasy mash-up, with Freud and Jung summoning a demon or some such silliness. And though Cronenberg has had a varied career as a director, many times shifting away from horror into drama, his films have always remained very distinctly “out there” and generally with one foot still firmly planted in genre cinema — be it the freaky leg scar sex in Crash, the hallucinatory nature of Spider, or the sudden gonzo gore of A History of Violence. This is the man who practically invented “body horror,” whose previously most main stream film was Eastern Promises, which was far too violent for my poor mother to sit through. Was A Dangerous Method going to reveal that Freud was into cutting, or that both men belonged to some weird secret sex cult? Was the film going to climax with Carl Jung pulling a gross organic gun-hand out of his chest-vagina and blow his brains out?

Coming from Cronenberg, the only thing shocking about A Dangerous Method is how completely normal it is. A straight drama told in a straight fashion. It’s only lean towards the obscene or salacious is that sex is very much at the film’s core. It is a movie about Sigmund Freud after all. But even here, the sex is largely just talked about, and talked about in an entirely relaxed often clinical way. You wouldn’t feel awkward sitting next to your grandmother during most of Jung and Freud’s sex chats. Though, when Keira Knightley gets spanked with a leather paddle during a sex scene you’ll probably regret watching it with your grandma. FYI. But I digress…

A Dangerous Method‘s central character is Carl Jung, and the film skips through the period of his life in which he had contact with Sabina Spielrein (Knightley), the mentally disturbed daughter of wealthy Russian Jews who becomes Jung’s first successful patient to be treated with Freud’s then controversial “talking cure.” In real life Jung (who was married) and Spielrein were rumored to have had an affair while Spielrein was studying for her doctorate and still Jung’s patient. The film of course takes the position that they did have an affair. A good and kinky one. Christopher Hampton uses this subplot to tell a larger story of sexual repression, and how this repression somewhat ironically spells the “downfall” of Jung — I put that in quotes because objectively speaking Jung had no downfall; the dude invented analytical psychology and is generally considered one of the most important intellectuals of the 20th-century.

Hampton’s screenplay is quite marvelous, and the best kind of biopic. Like Amadeus, it makes no attempt to impossibly cover the breadth of its subjects’ entire lives, but rather focuses on a specific portion/aspect that nonetheless allows us to grasp the characters in full. The film very much tells Spielrein’s story, who has a remarkable arc from her lowly beginnings, but Jung is the heart of A Dangerous Method. A somewhat tragic heart. Hampton portrays Jung as an idealist who gets sidelined by his own blindspots. He initially idolizes Freud, but becomes disillusioned with Freud’s staunch belief that all psychological quirks, ticks and disorders are rooted in sexual desire — something that the bad boy of psychoanalysis, Otto Gross (Vincent Cassel), jokingly yet astutely surmises is probably because Freud “never gets any.” What is most interesting about Hampton’s portrayal of Jung is that throughout A Dangerous Method, we are forced to constantly reassess the character. When Freud and Jung first meet, Freud seems a bit of a pompous dinosaur, completely impenetrable to Jung’s new ideas. In real life as in the film, Jung and Freud divided intellectually over Freud’s belief that it was not the place of the psychoanalyst to cure his/her patients; it was his/her’s aim to figuratively open the door to a patient’s mind so that the patient may look inside and better understand themselves. Jung (who unlike Freud was rather spiritual) felt there was an inherent cruelness to opening this proverbial door and not offering to help clean up the mess. As the film progresses, Freud’s way of thinking starts to seem a lot more logical and Jung starts to seem something of a noble fool, and even smugger than Freud. Though that is stretching things; the film doesn’t actually pick sides between the two men, and Hampton and Cronenberg rather blatantly show us that Jung was psychic — the film’s final scene is a doozy in this regard.

Like any film based on a stage play, A Dangerous Method is an acting showcase. Knightley gets the thankless task of having to play a crazy person. Playing someone who is out of their mind is quite possibly the hardest thing for an actor (who isn’t slightly crazy themselves; see Klaus Kinski) to believably pull off. Knightley does a valiant job, giving Spielrein a very unpleasant to look at facial tick. But nonetheless, the early portions of the film when Jung is first treating her, are rather weak and will likely have you worried the movie is only going to be average. Fortunately Jung cures Spielrein in due order and the story progresses. I quite liked the accent and speaking rhythm Knightley gives Spielrein once she is cured — her asylum-grade crazy acting isn’t very good, but she does manage to craft a convincing used to be asylum-grade crazy character, getting us to worry for her that the slightest misfortune will send her spiraling back to the hospital (and we don’t want that for a couple reasons). Vincent Cassel is only briefly in the film, in what is something of a comic relief interlude (though also marks a pivotal philosophical shift for Jung), and he is delightful. It’s Cassel as a horny cad trying to corrupt our pure Jung, obviously he is going to be delightful.

Michael Fassbender has very quickly become one of the best actors currently working, showing an astonishing range for the types of roles he can be dropped into with amazing results. And he is great here as Jung, infusing the character with just the right proportions of foppishness, aloofness, intelligence, and latent passion. But there is no denying that A Dangerous Method doesn’t come alive until we get our asses some Viggo. Christoph Waltz was originally set to play Freud, but was forced to drop out. At which time Cronenberg turned to his current muse. I’m sure Waltz would’ve done some stellar things with the character, but hot damn, Viggo sizzles as Freud. Which is all the more impressive considering the character never raises his voice or gives any flashy speeches; the most dynamic thing Freud does in the film is faint, once. Most of his scenes are casual two-person conversations. I have no idea what Freud was like in real life, so I have no idea how well Viggo plays the Freud, but he gives the character a smug electricity that makes every moment he’s on camera pop. He’s quite funny too, in a droll and sarcastic sort of way, savoring Freud’s many witticisms. This is a Viggo you don’t think of when you think of Viggo. I will be very surprised if I don’t see his name among the Best Supporting Actor nominatees next year (unless the studio decides to bump him to Best Actor and kinda fuck Fassbender). There should also be an honorary Oscar involved for Best Cigar Smoking, for his ever-present stogies.

The storyline between Jung and Speilrein is important and it works, but it’s the scenes between Jung and Freud that make this movie something excellent. Great dialogue, better acting, and Cronenberg has the confidence to keep things relaxed. In fact, I had no idea just how relaxed Cronenberg was keeping things until Freud and Speilrein finally have a scene together and Cronenberg tweaks the scene’s energy with some tense and well-placed music — which is one of the only moments in the film where Cronenberg allows himself to add a directorial flourish. The one Cronenbergian element that pervades the entire film is his spirit of levity, which nicely matches Hampton’s witty dialogue. This could mark a turning point for Cronenberg, as he handedly demonstrates that it is entirely within his power to not only make a perfectly non-sensational film, but to make a really good one too. Though, as much as I really liked A Dangerous Method, count me in the camp that hopes he doesn’t leave that chest-vagina hung up for too long.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars