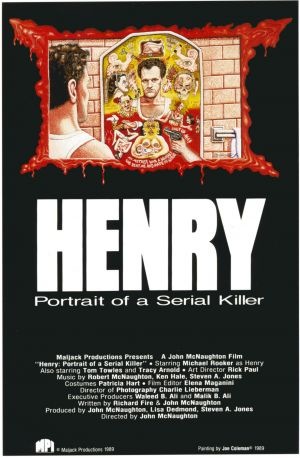

Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer is a movie that looks like a documentary from hell, and feels like a horror movie, though technically it’s neither. It’s probably the best movie I’ve seen that I hope I never ever have to see again. It’s like a Satanic Polaroid, impossible to describe without the adjective “disturbing”. It’s awful and ugly but that’s the entire point, and should never be understood as anything but thoroughly effective and well-made. Like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, it’s a triumph of craft that is so upsetting that it’s doomed to be dismissed for its content.

Shot on a miniscule budget in 1986 by Chicago director John McNaughton, Henry wasn’t actually released until 1990, and when it was, it was slapped with an X rating by the MPAA. Frankly, that’s an accurate rating. No child should have to know that this movie exists, because no child should have to live in a world where the events where it depicts happen, and it’s way more intense than your typical R-rated movie. It fairly honestly recounts the depraved and heinous acts of a man which can justly be described as evil. The acts were evil, if not the man — it’s not for me to judge, but it’s very hard to see how moral redemption can come for a human being who has done what Henry Lee Lucas has done.

Henry Lee Lucas was a real person, a drifter who eventually died after being sentenced to life in prison. He confessed to more than 600 murders, though the number was certainly false. He was convicted of 11 murders, a horrid number which is more than enough as it is. The movie does not seem to have been made to entertain; it’s rare to see a movie make the act of murder seem as horrible as it should be made to appear. It’s even more relevant today than it probably was back in 1990. We are currently living in a modern culture where our most popular dramaticized television programs — CSI, NCIS, SVU, choose your favorite acronym — turn murder and rape into “procedurals”, with quirky coroners and stock techno music and writers who comb the crime pages for plot inspiration. We are not pressed to consider how terrible and destructive that the violent acts of rape and murder truly are. McNaughton’s movie shoves the abominable, stinking, repulsive nature of these acts directly under your nose.

The great Michael Rooker began his long and impressive film career with the role of Henry. I wonder how much it typecast him for almost every role to come, since he is such a watchable and fascinating actor, but has most often played deranged creeps and villains. (See him currently doing his thing as a deranged racist redneck in AMC’s The Walking Dead.) In Henry, Rooker holds your interest captive, even as his Henry shows less recognizable human emotion than the mask-wearing killer Michael Myers in Halloween. He has a charisma that begins to explain why his only friend, Otis — the equally great and equally typecast Tom Towles — is so committed to him, although Otis has a literal attraction to Henry on top of his seemingly hypnotized fascination with him.

Henry commits murders as if it were his job. The brutally effective opening sequence intersperses Henry’s workmanlike behavior with extended, graphic shots of his murdered victims, eyes open and bodies bloody, with the sounds of their struggles and screams being played over the images (and the convincing, upsetting musical score.) Henry kills as a matter of habit. There is little reason or passion behind his actions. When someone crosses his path, particularly someone who seems like they won’t be missed, such as a hitch-hiker or prostitute or pawn shop owner, he murders them, usually with the tools at hand. Then he has his ways of disposing of the bodies.

His buddy Otis catches wind of his pastime, then jumps right in without much hesitation or remorse. But Otis seems to enjoy it more, and when he teams up with Henry, the atrocities somehow escalate, most notably in the rape and murder of an entire suburban family, an episode which Henry and Otis videotape and then re-watch after the fact. It’s a testament to the uncommon work of the filmmakers and actors that it’s somehow even more horrible to watch Henry and Otis sitting on the couch, almost bored, as they watch the terrible events on screen, a sight which is enough to traumatize the average viewer. The end begins when Otis’s sister, Becky — the underrated, unremembered and unknown Tracy Arnold — comes to stay with Otis and falls in love with Henry, despite almost immediate awareness of Henry’s murderous nature. Becky is like a mouse in a lion cage, seemingly impervious and undeterred by the constant threat surrounding her. In one of the few concessions this movie makes to dramatic convention, that’s not bound to last.

Everybody involved in the making of Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer was brave. They have to have known that if this movie worked, which it does, that it would shock and horrify audiences. Some critics, such as Roger Ebert and the invaluable Dave Kehr, recognized right away the horrendous excellence of the film, and it gained a certain notoriety. I was aware of this movie long before I ever saw it, and I was unprepared for how unsettling and how well-made it truly is. Again, I have to lament how Michael Rooker and Tom Towles, while beloved by knowing genre fans, are so unrecognized for their work in this film — and in those subsequent beloved genre films. Rooker is a fierce talent (see Sea Of Love or Slither) and an amazing interview (start here), and Towles is the kind of unforgettable face who still manages to bushwhack you when he turns up in mainstream films, such as Miami Vice. I don’t get the sense that either of these guys give a fuck about Oscars, even though they’ve been working at that level, but then again the Academy don’t give out Oscars for bravery.

If you yourself are feeling brave, you can track down this movie. It’s a lot easier to do these days. Where once Henry lingered on a ratings board shelf for four years, I was able to watch it on Netflix Instant. I guess for every way that times change for the worse — note aforementioned popularity of certain TV shows — there is another way in which times change for the better. Arguably.

But seriously — no one’s kidding about that X rating. And make no mistake: That’s an X for ‘scary as all hell.’