Maybe it’s because I’ve been waist deep in Warner Bros’ John Wayne/John Ford box set the last two weeks, but The Hidden Blade, the new film from Twilight Samurai director Yoji Yamada, really reminded me of one of Ford’s more elegiac Westerns. Hidden Blade is set at the twilight of the age of samurai, as Western artillery and military concepts begin to come to Japan. The medieval world of the Japanese is coming to an abrupt end, and in many ways the film’s protagonist, the provincial samurai Katagiri, can’t make the adjustment – except maybe when it comes to modern concepts of love.

Maybe it’s because I’ve been waist deep in Warner Bros’ John Wayne/John Ford box set the last two weeks, but The Hidden Blade, the new film from Twilight Samurai director Yoji Yamada, really reminded me of one of Ford’s more elegiac Westerns. Hidden Blade is set at the twilight of the age of samurai, as Western artillery and military concepts begin to come to Japan. The medieval world of the Japanese is coming to an abrupt end, and in many ways the film’s protagonist, the provincial samurai Katagiri, can’t make the adjustment – except maybe when it comes to modern concepts of love.

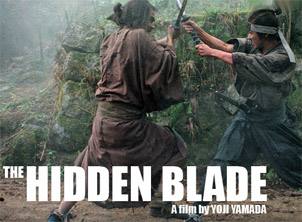

Yamada is very sparing with his camera – the framing is always beautiful, but his camera tends to stay still. It’s an old fashioned way to shoot a movie, but it’s also refreshing – actors move about within the frame, as opposed to the camera following them. It gives the movie a more formalized feeling, perfect for the rigid social world of Japan, a world that’s about to come crumbling down. The old fashioned technique heightens the film’s one major fight scene – we can see what’s going on as the characters clash, and since the duelers are friends, their moves become character elements, not just action elements.

Katagiri is a man caught between two worlds. His father committed seppuku years ago over a problem with a bridge project. The problem wasn’t his fault, but he did the honorable thing, and it seems like not many other men would do the same. As a result of the suicide, his family has lost prestige and income – the father’s honorable choice turns out to not be as honored by those around him. Katagiri grows to be a seemingly confirmed bachelor; the truth is that he is in love with the family’s servant, Kie. Nothing can ever become of that love because of their different castes, and when Kie is married off to a merchant family, Katagiri assumes he will never see her. But he does come across her again, three years later, and he learns that her new family is abusive and that Kie has fallen terribly ill. In a most un-samurai move, he takes her from the merchant family and brings her back to his home, where she will recuperate. The situation is scandalous, though, and Katagiri’s position becomes more and more tenuous.

Things only get worse for him as an instructor from Edo arrives to teach the local samurai how to fire cannons and advanced guns and march in formation, English style. While they comically can’t get the hang of it, a darker subplot forms – one of Katagiri’s friends – they studied swordsmanship together – has been fomenting rebellion in Edo, and has been sent home to live out his days as a prisoner, denied the honor of suicide. But the friend breaks out of his prison and holds a family hostage, looking to die in battle. The authorities suspect Katagiri of working with the rebel, and send him to dispatch his friend, partially to prove his loyalty.

What’s fascinating about The Hidden Blade is watching the collision of eras, with Katagiri caught in the middle. He loves Kei, but is willing to let her go because that’s what he is supposed to do, yet at the same time he sees everything he ever knew about honor and duty becoming extinct around him. Yamada builds on this theme throughout the film, culminating in a scene where guns steal the honor and glory of a battle. And the hidden blade of the title comes to have many meanings, from a secret killing technique to Katagiri himself. Unfortunately I found this aspect much more engaging than the love story; maybe it’s because I’m an outwardly emotional person, but I always find stories of denied love to be distancing. It was one of my main problems getting into Brokeback Mountain, and it’s one of my main problems with The Hidden Blade.

The pacing of The Hidden Blade is deliberate, but not dull. That said, Yamada stretches very little story into two hours. This is one of those films where the journey is more important than the destination; the film is filled with beautiful images and telling details that excuse the elongated running time. As gorgeous as the movie is, what makes The Hidden Blade truly worth seeing is Yamada’s meditations on duty and honor and family, things that I think he and Pappy Ford could have spent some time talking about, after they finished discussing shooting beautiful landscapes.