Of the classic Universal movie monsters, my favorites have always been the Wolfman and the Gill Man. I love them all, don’t get me wrong – Count Dracula, The Invisible Man, The Mummy, Frankenstein’s Monster and his Bride – they’re all great. It’s just personal taste: since I was a little kid I’ve adored animals, so the more animalistic characters have that much more of a place in my heart. As a result, I’ve not revisited any of the Universal monster pictures as much or as recently as I have The Wolf Man and The Creature From The Black Lagoon. (Those two I seem to re-watch every couple years.)

In an effort to broaden my palette, I recently went back to the 1931 Universal telling of Frankenstein.

Wow.

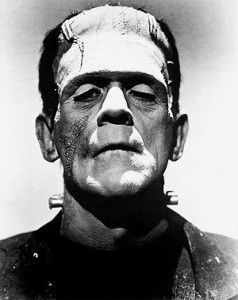

Mary Shelley’s novel had been around for one hundred years before James Whale directed Frankenstein in 1931, but ever since, the image of The Monster that has been imprinted on our cultural recollection is that of the amazing make-up design by Jack Pierce, painstakingly applied over Boris Karloff’s distinctive features.

Let’s talk about that make-up for a minute:

It’s just phenomenal. It’s a thoughtful, graceful, and imaginative design that absolutely makes sense for a character who was literally stitched together from pieces of stolen corpses. At first glance, it still retains the ability to be upsetting. At the same time, there’s just enough tenderness and depth of emotion to that face that it can be understood to charm that poor little Maria by the river, the same way The Monster has charmed millions of children across the world in the century since.

The look of The Monster can hardly have the same impact today that it must have had when the movie was first unleashed on an unsuspecting audience – in fact, Frankenstein begins with a brief prologue where one of the actors comes out on a stage proscenium and gives an ornately-worded disclaimer warning the audience that what they are about to see might shock and disturb them. Back then, the audience probably needed the warning! Remember, eighty years later we’ve all grown up on the image of Frankenstein’s Monster, on Halloween masks and episodes of Scooby-Doo and on boxes of FrankenBerry cereal. Back then, the film medium was still in its infancy. Besides The Phantom Of The Opera and The Hunchback Of Notre Dame a couple years earlier, nobody had seen anything this spooky or gruesome on screen. Audiences certainly weren’t inundated with horrific images the way modern audiences, exactly eighty years later, have been thoroughly prepared to expect and accept.

So in that first official appearance, where the Monster lumbers out of the shadows, there’s a reason why James Whale chooses to have his camera linger on a close-up for as long as he does: Audiences needed time to react, and then to recover. This is what they were waiting to see, what they wanted to see, but when it finally arrives, it stops the movie cold for a moment before the movie can start again.

James Whale’s direction is full of brilliant and memorable decisions like that one. Those like me who haven’t seen Frankenstein in a while will be struck by the originality of the opening scene, even by today’s standards. The first real scene (after the disclaimer and the credit sequence) takes place on a barren hilltop at a funeral, from which Dr. Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and his wretch of an assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye, originating the “Igor” archetype that horror films quickly absorbed) are about to steal the freshly-buried coffin in order to harvest the body parts within. The camera, set at severely tilted angles, glides past the downcast faces of the mourners and roves past a chilling Grim Reaper statue in the background. It feels like the funeral itself is sliding off the edge of the world. The scene is starkly bizarre and terrific, just like the rest of the movie which is to follow.

Again, this was a movie made near the beginning of sound in cinema – directors were still figuring out the film medium. Frankenstein isn’t quite technically perfect; there are a couple jump cuts in noticeable places – but it’s an astounding creative achievement considering the era, and it still resonates today. The tracking shot of The Monster in the daylight for the first time, staggering through the underbrush, or the famous wide shots of the enraged villagers later on, burnishing torches in the night sky – these are unforgettable, myth-making images. There’s also more humor in the movie than might be remembered, courtesy of Dr. Frankenstein’s blowhard of a father (Frederick Kerr) and a character known as The Burgomaster (Lionel Belmore), who clearly proves to be amazing even before he farts out his first sentence.

In short, I highly recommend to all to go back to Frankenstein when choosing movies to put into rotation this Halloween. There is good reason why the classics endure, and I mean this in reference to James Whale’s rendition as much as Mary Shelley’s landmark novel.

The way I watched Frankenstein was on DVD, via the terrific package that Universal released a couple years ago. Among many other great supplemental features, there is an erudite and informative commentary by Sir Christopher Frayling, a name I know well because I am a massive Sergio Leone nerd and Sir Christopher is considered the world’s foremost authority on the director of the so-called “Man With No Name” trilogy. He’s plenty knowing on the subject of Whale and Karloff as well. The movie really does deserve the scholarly treatment.

Any thoughts on Frankenstein? Hit me up!

Below is a quick sketch I did of Frankenstein’s Monster.