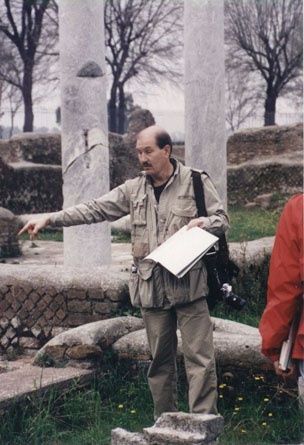

When Fox screened The Omen to critics and journalists in New York City a few weeks back, director John Moore did a Q&A along with Dr. L. Michael White, Director of the Institute for the Study of Antiquity and Christian Origins at the University of Texas at Austin. I’ve always been fascinated by early Christianity and the historical aspects of the religion, and my bookshelf is packed with books ranging from the wacky (The Passover Plot) to the excellent (Elaine Pagel’s Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas), so the idea of talking to an expert in the subject was too much to pass up.

When Fox screened The Omen to critics and journalists in New York City a few weeks back, director John Moore did a Q&A along with Dr. L. Michael White, Director of the Institute for the Study of Antiquity and Christian Origins at the University of Texas at Austin. I’ve always been fascinated by early Christianity and the historical aspects of the religion, and my bookshelf is packed with books ranging from the wacky (The Passover Plot) to the excellent (Elaine Pagel’s Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas), so the idea of talking to an expert in the subject was too much to pass up.

Dr. White has published seven books, including one that I currently have coming to me from Amazon, and which he mentions in this interview – From Jesus to Christianity: How Four Generations of Visionaries & Storytellers Created the New Testament and Christian Faith (you, too can order this book through CHUD by clicking here). He was also the principal historical consultant on two PBS specials, From Jesus to Christ: The First Christians and Apocalypse! Time, History and Revolution, both of which he also co-wrote. Dr. White has also published many articles, and currently teaches undergrad and graduate classes at UT – for more on his impressive credentials and history, check out his site at the UT webpage by clicking here.

Dr. White was kind enough to make some room in his schedule to talk to me on the phone last week. In this exclusive interview he walks me through some of the more important and finer points of the end of the world, the Book of Revelation and some aspects of the diversity of the early Church. I could have talked to Dr. White all day, but I think you’ll find that in our half hour we managed to cover some interesting topics.

Q: Last week I spoke with John Moore, the director of The Omen, and he said one of the differences between The Omen and The Da Vinci Code is that The Omen is based on Biblical fact (that interview is here). What’s your take on that?

White: John and I talked about this a good bit. It’s the clear that the movies, both the  original and this one, are more directly cued to ideas from the Book of Revelation in the New Testament. Whether you can call that fact or not is another question, it seems to me. That’s the issue that I think is at hand here.

original and this one, are more directly cued to ideas from the Book of Revelation in the New Testament. Whether you can call that fact or not is another question, it seems to me. That’s the issue that I think is at hand here.

The movie assumes that there is an ability to look at current events and say, ‘Ah, these are the signs – or the omens – that one sees described in the Book of Revelation now coming to fruition, and that means we are approaching the arrival of the Antichrist and some sort of end of times scenario. That’s what I think he’s alluding to as quote unquote Biblical fact. The difficulty is – is that the proper way to read the Book of Revelation?

To add another component of this, of course it is the case that a lot of different groups read Revelation in that way. The Left Behind novels, for example, are also doing something similar, but with an entirely different system of reading current events as signs of the end of times. They would be quite at odds with one another.

Q: And they’re not taking everything from Revelation, right? They’re taking parts from other books in the Bible. The Rapture isn’t in Revelation.

White: Correct. Nor is Antichrist. There is no Antichrist in the Book of Revelation. All of these systems do a little bit of that. If you remember there’s a scene in The Omen where the photographer says, ‘Some of this is Daniel, some of this is Revelations.’ All of those systems, in order to make it current events, have to do a little picking and choosing from different books.

But in any case there are dozens of these kinds of systems. David Koresh had one, the Left Behind novels have a different one – and by the way, the Left Behind series works on the assumption that this is the proper interpretation of the Book of Revelation. The Omen, the premise there is a different system of interpretation, but similar in terms of process: x in the Book of Revelation equals some current event we see now, ergo we are watching the unfolding of the events leading to, in this case, the coming of the Antichrist.

Q: The Book of Revelation has been prominent in our popular culture for decades, but what’s weird about Revelation – and I’m not a Biblical scholar – but it doesn’t read like a lot of the rest of the New Testament.

White: This is where the issue of how to read the Book of Revelation is crucial. No serious Biblical scholar would read the Book of Revelation as having any predictive or prophetic value for current events. It has nothing to do with current events. That’s where the claim about “fact” breaks down.

That’s because the two issues here are: a, what is the Book of Revelation in genre – that is, why is it so different from the rest of the New Testament; and b, how does that genre work in the first centuries as a form of talking about events? That genre is what we call apocalypse, or apocalyptic literature. The Book of Revelation, the title of it in Greek is The Apocalypse of John. The word apocalypse just means “revelation.” But apocalyptic literature does in fact have this quality of florid imagery and visions which are assumed to be fulfilling events. The problem is that the literature always pitches back and is running up to some modern time, is the way it is written in antiquity. The other thing is that yes, it looks strange to us, but if you were living in the First Century AD or the First Century BC, you would know this is a very common form of literature within Jewish tradition. In fact there are about thirty of these things out there at the time.

Apocalypse of John. The word apocalypse just means “revelation.” But apocalyptic literature does in fact have this quality of florid imagery and visions which are assumed to be fulfilling events. The problem is that the literature always pitches back and is running up to some modern time, is the way it is written in antiquity. The other thing is that yes, it looks strange to us, but if you were living in the First Century AD or the First Century BC, you would know this is a very common form of literature within Jewish tradition. In fact there are about thirty of these things out there at the time.

Q: How did this one become the one we ended up with in the New Testament?

White: Because it’s the one we end up with in the New Testament! It’s a complicated story. It wasn’t readily part of the New Testament, and it in fact was one of the controversial books. It was not widely accepted until the end of the 4th Century, when it was actually included in the Western Canon in 394. Up until that time it was quite controversial – people didn’t think the Apostle John really wrote it, for example. It was either attributed to a different John or whatever by contemporaries of these discussions. It wasn’t widely accepted. For example, in the Greek Orthodox canon it was not part of the New Testament until the 12th Century. And it is still not in the Syrian Orthodox Christian New Testament to this day.

So it hasn’t always been there. It is part of the Western Canon, the Latin Medieval Bible of the Catholic Church, and in part even there it was not meant to be read literally as predicting events. It’s main function is as showing sort of the Last Judgment kind of ideas, more so than any predictive quality. The other thing about the movie is that the Catholic Church does not ascribe any predictive value to the Book of Revelation for current events.

Q: I’ve read that some people look at the Book of Revelation as being very specifically about Rome in Israel in the First Century.

White: The Book of Revelation is actually about the whole series of events at the end of the First Century looking back at the destruction of Jerusalem in the war, the first revolt against Rome. The Beast of Revelation is actually the emperor Domitian. If you look at my book, From Jesus to Christianity, at the end of Chapter 11 there’s a long discussion of the Book of Revelation in these terms. But generally that’s the way historians and New Testament scholars would read it – that it’s specifically an apocalyptic interpretation of the events surrounding the war and its aftermath for the next twenty years or so at the end of the First Century. Indeed it does portray the Roman Empire as a satanic oppressor of the people of God.

Q: This weekend the number one movie was The Da Vinci Code, which has its own brand of Biblical mayhem going on. One of the things that’s interesting about the movie and the book is that, while much of the history is off-base, there are ideas and concepts that seem to be based on reality, such as the fact that the early Church was not all in agreement on what should be in the Bible, which you mentioned before. How important is that to understand today when we’re looking at the Bible? White: The Da Vinci Code is all fiction, and even though it’s based on a crackpot theory known as the Holy Blood, Holy Grail theory, but the point of the discussion about diversity in early Christianity is something scholars do talk about. If you look at my book you’ll see that the diversity issue is a very important one, and one to say that is this: in one sense if it were not for the growing diversity in early Christianity in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Centuries, there would have been no need to forge an orthodoxy. So diversity and orthodoxy are two sides of the same coin. One way you see that diversity is in the proliferation of new Scriptures, or new documents. So both the Gospel of Mary Magdalene and the Gospel of Judas would have been part of that proliferation of diversity, the Gnostic Gospels.

White: The Da Vinci Code is all fiction, and even though it’s based on a crackpot theory known as the Holy Blood, Holy Grail theory, but the point of the discussion about diversity in early Christianity is something scholars do talk about. If you look at my book you’ll see that the diversity issue is a very important one, and one to say that is this: in one sense if it were not for the growing diversity in early Christianity in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Centuries, there would have been no need to forge an orthodoxy. So diversity and orthodoxy are two sides of the same coin. One way you see that diversity is in the proliferation of new Scriptures, or new documents. So both the Gospel of Mary Magdalene and the Gospel of Judas would have been part of that proliferation of diversity, the Gnostic Gospels.

Now, one point I’ve made, and in fact I was featured on the UT web site last week in a banner article, which you can see in the archives there, and it’s in my book and other places, but one of the points that I would make is that these documents are not claims on history. They’re not an alternative version of the history in any strict sense, partly because they presuppose the traditional Gospels in a lot of ways. In other words, to have something like the Gospel of Judas, you have to know the traditional Judas story in the Gospels, and then it inverts it. You can’t have the inversion unless you’ve got the starting point back in the traditional stories. That shows they know the other tradition, and these are efforts to do a theological reinterpretation by telling the story in another way. And that’s where a lot of these things come in, and that’s what’s confusing to a lot of people – even the National Geographic special they aired a few weeks ago on the Gospel of Judas, they can’t get their mind around this. If it’s ancient it must be a claim on history – which is not true. It’s an ancient document, 2nd or 3rd Century, but it’s a theological exploration.

Q: How important is history when we’re discussing Biblical matters? You’re obviously very well-versed in the history of the early Church, but so much of it is based in faith anyway. Does the history make a difference beyond being interesting?

White: Yeah, it makes a huge difference. You can’t do this without dealing with the history, and if you do it can be taken in any direction people want – just like David Koresh. History is the qualifier, history is the main issue in this.

Let me make clear what I mean by history: It’s not that the documents are literally historical, but rather you read them in a historical context, and that’s a crucial difference. For example I would not say that even the Gospels in the New Testament are literally historically accurate in every detail. No scholar would say that. But the key point that I’m getting at is that to understand these documents, whether it’s the Gospels or the letters of Paul or the Book of Revelation, you have to locate that document in its proper historical context. Meaning when it was written, why it was written, for whom it was written. What is the genre, how is that working. What are the circumstances which are generating this particular document. Then and only then can you make sense out of what this document is doing.

Another dimension of the history is that there’s a history of how later generations read that document, or in some cases misread that document, as in the case of the Book of Revelation. We call it the history of misinterpretation. But there’s another dimension of history, the history of why did people take it in another direction. There’s another situation of the historical context of Joaquin de Fiore in the late 12th/early 13th Century during the Crusades reading the Book of Revelation as predicting the victory of Richard Lionheart over Saladin. Which, by the way, it failed.

The point is that’s another way in which the ongoing history of the usage of a document comes in.

Q: That seems to be going on to this very day, since it could be arguing that there are aspects of modern US foreign policy that could be attributed to readings of Revelation.

White: There’s absolutely no question whatsoever that for a number of years now that the very predictive reading of Revelation has been very influential on a large segment of thinking in the American population and concomitantly with the foreign policy of those same people. In other words it’s a very conservative Religious Right agenda to see these things happening.

Q: Why do you think that is? At the end of the 90s I ascribed a lot of this to millennial issues, but it remains popular. Why is it still so prevelant?

White: It is the same millennialism issue, and it has been growing since the late 70s and the 80s with the resurgence of Evangelical Christianity in the US. Evangelical Christianity is, or at least a large segment of it, is pre-millennial in its theological orientation. That’s the form that’s in the Left Behind novels, and Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth and all that.

What’s interesting about this system of interpretation, which is called Darbyist Premillennialism, is that the year 2000 was not the key issue. It’s that the system workd, and the specific number is something they don’t have to predict. What you’re always doing is looking for signs that match up so you can say it’s getting close. That’s why it hasn’t tailed off since 2000 came and went – at least not for this kind of prophecy belief. For others the anxiety dissipated. And that’s why you might expect them to let go of it now, but it doesn’t work that way. I would say that’s where a lot of this is coming from, that segment of America –and it’s very American, in terms of Christian belief – this deeply entrenched, premillennial way of reading the Book of Revelation has been extremely influential on the conservative right.

Q: You brought up Hal Lindsey – his claims were so specific but they didn’t happen. 1988 came and went and Christ didn’t return and the end times have not happened, but that doesn’t seem to deter people.

White: What they do is say, ‘Oops, we miscalculated on something, but we’ll recalibrate and move on.’ That’s typically what happens. But yeah, it’s basically the same system – Hal Lindsey and the Left Behind novels are exactly the same system of interpretation. Interestingly enough, The Omen is not that system. It’s a different set of interpreting moves – for instance there’s no Rapture in The Omen. It’s a different kind, and in some ways, a simpler kind of system.

move on.’ That’s typically what happens. But yeah, it’s basically the same system – Hal Lindsey and the Left Behind novels are exactly the same system of interpretation. Interestingly enough, The Omen is not that system. It’s a different set of interpreting moves – for instance there’s no Rapture in The Omen. It’s a different kind, and in some ways, a simpler kind of system.

Q: It also seems like a weirdly gentler system, as the Left Behind novels end with Christ risen and laying waste to millions of people, which rings weird to people who understand Christianity as a religion of love.

White: Yes, that is one of the key differences. Theologically speaking, the difference is this – in the Left Behind kind of approach, the good are taken away in the Rapture, and then Christ allows for the Tribulation – that’s their term. So you get the Rapture and the Tribulation. So those are the two characteristic terms used in premillennialist interpretation. The Tribulation is the time when Christ or God allows for the punishment of everybody else, or they have a hand in doing it directly. Contrast that with the kind of interpretation you see in The Omen where, to some extent, it is the breaking in of the Satanic element that is the cause of the sufferings that are taking place in the opening of the movie, and those are the signs that things are happening. In some ways that is a bit – well, it’s just a different take on what those signs are in the Book of Revelation. But you are right about that being a little more benign, shall we say.

Q: There’s a point in one of the Left Behind novels where Christ slaughters millions of people. I find this terrifying, in a genocidal way.

White: I agree with that. Theologically speaking I have no sympathy whatsoever with that way of reading Revelation. And I don’t think it’s consistent historically consistent with what’s going on in Revelation. From a normative viewpoint I find it very problematic.

Now I did the PBS documentary on Apocalypse, and we tried to show this history of interpretation and how it’s coming out, but the point is that it’s a very different reading than anything that existed prior to 1888, roughly, when it was invented.