Recently

Recently

I was feeling the urge to write an editorial about film criticism.

Someone had written me a nasty email about the numerical ratings in my

reviews, which they felt didn’t match up with what I had written. The

person said he wouldn’t take my reviews seriously anymore. I was a

little dumbstruck. People take my reviews seriously? Then I began to

see how silly that letter was – if you’re reading my review and

understand what I am saying, what does the score matter? It’s all about

the text, man.

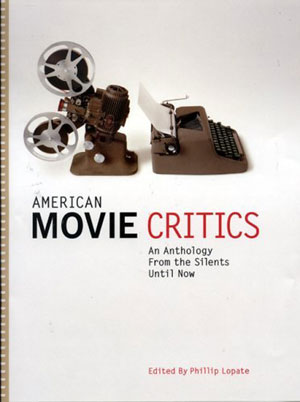

Before I could write that essay I picked up a copy of American Movie Critics,

compiled Phillip Lopate. Reading through the book, which gathers some

of the best film writing from the silent era all the way through the

end of 2005, I realized that the book said everything I wanted to say

just by virtue of having so many damn great reviews and essays. I

looked up Lopate and he agreed to talk to me about film criticism.

Lopate

knows a thing or two on the subject. He’s one of those writers who

seems to be able to work in every field – he’s published novels and

essay collections, written about movies for The New York Times, Vogue,

Esquire, Film Comment, and Film Quarterly (among others), and he’s

taught writing to children and university students.

When you’re done reading this interview, I want you to come back up to the top and click here to buy American Movie Critics from Amazon.

It’s a big, meaty hardcover that belongs on the shelf of any serious

movie lover. It’s a compulsively readable collection that’s filled with

the kind of film writing that can change the way you look at movies.

It’s funny, it’s startling, it’s fascinating. Yes, that’s a sad attempt

to get blurbed on the softcover. I’ve already learned the most

important lessons of criticism! (But seriously, the book is great)

Q:

In your book you go through the history film criticism in America,

reprinting movie reviews from the silent era to the end of 2005. How

many reviews did you have to read to put this book together?

Lopate: I

would say I read ten pages for every one page I finally selected. I

read tons. Sometimes even with critics whom I knew I was going to put

in it was a problem of what to select – they wrote well and everything

they wrote was good.

Q: Was there something you couldn’t fit in there that you wish you could?

Lopate:

There were plenty of things I couldn’t fit in there, but it’s a big

book. In terms of the history, the period from 1917 to 1980 there’s

everything I wanted to go in. Obviously there are a lot more

contemporary writers I could have included, but to me the main press of

the book is in getting that history right.

Q:

A lot of the reviews in this book will be ones most people haven’t

read, especially reviews from the silent era. What was the most

surprising thing to you from that period?

Lopate:

It’s interesting to see writers try to develop the persona of the film

critic when there was no such thing as film criticism. They had to

stumble along and project some sense of authority. Sometimes they

borrowed from other art forms, like Vachel Lindsey did when he talked

about painting and sculpture and architecture. Sometimes they try to

argue that movies are unique and they try to sever the relationship

between movies and other artforms, the way Gilbert Seldes warned movies

should not mess around with theater. Sometimes they were facetious and

signaling the reader that this stuff isn’t to be taken that seriously –

after all it’s only a movie. Sometimes they took a very sacramental,

serious view towards the art movies, saying this is what we’re waiting

for, now it’s an art form.

There

were a lot of different ways of handling it and these strands, these

tensions, continued on – are movies primarily a form of entertainment

or are they an art form? So you have people like Manny Farber defending

the B-movie and the film noir movie and the cheap action movie, saying

these movies are more important than the grade A, big message movies.

Q: And you have a great piece from Hoberman talking about how truly bad movies can be more transcendent than great ones.

Lopate:

Exactly. All of these movies gave the writers opportunities to think on

the page. What I was trying to do with this book was to suggest that

film criticism is a form of essay writing; what’s really important is

not necessarily whether a critic likes a movie or doesn’t like a movie

but what he brings back, what he thinks about.

Q:

A lot of people have been claiming for years – and it’s mentioned in

the book, especially in regards to Susan Sontag claiming cinephilia is

dead – that there’s a crisis in criticism. Do you think that analysis

in essay form is going by the wayside and that the “Consumer Reports”

school of reviewing is winning out?

Lopate:

I think there will always be room for both. As long as challenging and

intriguing movies come along that you can’t quite get your finger on

right away, you’re going to need to circle around them and look at all

your different responses. For instance a movie like David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, or Eyes Wide Shut

by Stanley Kubrick, which I have a Jonathan Rosenbaum review of –

they’re going to need some unpacking. I think that just as the essay

form isn’t dead, film criticism as an essay form isn’t dead.

Susan

Sontag was a polemicist. She stirred up people and touched a nerve with

that comment, but perhaps that was an exaggeration. It’s true that a

lot of the support mechanisms surrounding movies have atrophied, but I

think that great, serious, wonderful movies are being made every year.

Q:

I think that today movies occupy a central place in popular culture in

a way they haven’t in decades. On the other hand I also feel like we’re

seeing a generation growing up that has access to DVDs and cable

channels like Turner Classic Movies, but aren’t getting immersed in the

history of cinema. Do you think there’s a cultural amnesia going on,

where anything before 1980 is ignored?

Lopate: I

do think there’s a lot of resistance on the part of some young people

to black and white movies, silent movies, movies that look old

fashioned in their eyes. Certainly in the 60s and 70s there was a great

emphasis on film history, but film history has gotten longer. When I

was first coming to movie love in the early 1960s, there’d only been 60

years of movie history, if that. Now there’s been 105, and it’s harder

to absorb it all. We’re more aware of how there are other places to be

heard from, other parts of the globe. It’s a bigger job.

It’s

great that DVDs that are beautifully turned out are coming. I think

it’s a dream come true, in a way. You can develop your own collection

of classics.

Q: Is it

possible that that cheapens things? When I was younger if you wanted to

see a rare film, you had to hunt it down and go out of your way to see

it. Now you can go to Amazon.com and get it with two day shipping.

Lopate: You still want to see it on a big screen, don’t you? I just went to see this Jean-Pierre Melville movie, Army of Shadows,

which was restored. It was really fantastic, and I had to see it in a

big theater to get the impact. There’s still a great desire to see it

on a big screen. At least for me!

I’m

not a kind of industry insider. You have to understand that I edited a

book of film criticism; I’m not a prophet who can see what’s going to

happen in terms of grosses and stuff like that.

Q: A lot of film critics these days do try to talk about stuff like that. Do you think that has a place in film criticism?

Lopate: You

can certainly always reflect on the impact of technology, for instance.

In the anthology I put in a lot of stuff about when talkies came in,

when color film came in. 3D, widescreen – all these things were seen as

threats. There’s this compulsive need to protect ‘your’ cinema, but

cinema keeps absorbing from other places; it’s a very impure art. So

yeah, I think it’s the job of the film critic to speculate about what’s

happening. I’m just saying I can’t speculate!

I’m

on the New York Film Festival selection committee and I’m going to go

to Cannes in two weeks. The last few years I’ve been going to Cannes

I’ve been seeing some incredible movies, and they’re not always the

ones by the directors you think are going to be incredible. Sometimes

they surprise you.

Q: What are some of the films that you’re looking forward to this year?

Lopate:

There’s a Nanni Moretti movie – he’s an Italian director – that I’m

looking forward to. A lot of my favorite directors didn’t make movies

this year, but last year for instance there was a film I saw at Cannes

called The Death of Mr. Lazarescu,

a Romanian film. I didn’t know the director and it was about the best

film I saw last year. You never know, you have to be open, and I think

one of the jobs of the film critic is to be open.

Q:

It’s tough to go to a film festival where there are so many movies

playing and knowing what movies to see. How do you make those decisions

on a daily basis at a big festival?

Lopate: I

handicap it like somebody betting at the races. If I’ve seen a film by

someone before and there’s something there, I definitely want to see

his or her film. Like Sofia Coppola’s film Marie Antoinette is going to be at Cannes and I was sufficiently interested in Lost In Translation that I want to see it.

Past

record is one thing, but when you’re in a film festival it’s like a

beehive and you try to gather information from the other bees. You end

up asking complete strangers ‘Was that film any good?’ because you’re

so desperate for some kind of insight, some tip. And of course

sometimes they’re completely untrustworthy!

Q: It’s surprising how exhausting big film festivals are.

Lopate: They

are. They’re like big trade fairs. My wife and daughter say, ‘When can

I go to Cannes,’ and I’m like God, it’s not a family friendly place!

It’s brutal. I’ve seen a French policeman throw a lady down the stairs

because she didn’t have the right pass. It’s rough.

Q: Bare knuckled film criticism.

Lopate: Exactly. It’s not all starlets and champagne.

Q:

Your book only includes print critics. The last few years has seen the

rise of film criticism on the web – what’s your take on internet

criticism?

Lopate:

I think that there’s inevitably going to be some very important film

criticism on the web. I ran out of pages, basically, and I felt my

first loyalty was to print critics, because that’s the story I wanted

to tell. I do think that a lot of writing on the web about movies has a

stream of consciousness, semi-undigested quality that doesn’t have the

kind of economy and elegance that I’m looking for in the best stylists.

But I think there are people who are writing well on the well, and I

hope that there will be standards of writing that are higher.

Q:

What do you think the egalitarian aspects of the internet will do to

film criticism? Today anyone can get a website and with a couple of

phone calls get themselves on the screening lists for every studio and

distributor. Now almost anybody can get into the game.

Lopate:

I’m excited that people who wouldn’t have many venues to break into

will have a chance to learn a craft and to experiment. It’s proof that

there’s a great need to write about movies – not only is film criticism

not dead, but you’ve got a lot of amateurs out there who are trying to

do it and some of them will become film critics. So I don’t feel at all

threatened by that, I think it’s great. When young, wannabe critics

turn to me and ask where they can get published, there aren’t that many

places, so the web is a salvation in a way.

But

of course you need to get paid, that’s the problem! But you can hone

your craft, you can learn a lot – how to approach a movie, quickly get

a take on it and how to approach a piece. You have to start somewhere.

As a writer I began at open mic poetry readings. Everybody has to start

somewhere.

Q:

I’m interested in ethics in film reviewing. Some of the big critics,

the bigger they get the more ingrained in the system they get. Whether

it’s Pauline Kael seeing early cuts of movies by her favorites or Roger

Ebert schmoozing it up with a director at a party, where do you see

that line, and how important is it for a critic to stay on the right

side of it?

Lopate:

I think it’s a good idea to stay on the proper side of it. Fortunately

a lot of film critics have such dyspeptic personalities they never

really get that close to the film directors and they remain sour

loners. [laughs] But a lot of them do, and you develop friendships with

directors. I can tell you as somebody who’s on the New York Film

Festival selection committee that it comes down to friendship versus

personal taste. I think it’s a good idea not to develop such good

friendships with people in the industry, because you can be manipulated.

Q: Do you think most film critics at heart want to be directors?

Lopate: No.

Some do, though. If you look at people like Paul Schrader, for

instance, he was an excellent film critic who became a director. Peter

Bogdanovich was another. I think a lot of film critics have a

screenplay in their drawer, they secretly fantasize about doing

something in the movies. It turns out to be a lot harder than you

think, though. I’ve written all of my life and I wanted to make arty,

independent movies. I made short films and I discovered there’s an

enormous difference between knowing film as an aesthete and being

behind the camera and trying to get three dimensions to work in two

dimensions.

Q: I

really like the book, but I feel like I may be cheating by reading the

book out of order. Should I be reading it front to back?

Lopate: Read it any way you want. When you think of the fact that I read ten pages for every one, you’re entitled to jump around.

Q: Do you think it’s a different experience reading it front to back?

Lopate:

I think you may end up reading it both ways. It’s impossible to resist

the temptation of reading what somebody you’re interested in has to say

about a movie you’re interested in. But eventually, if you play with

the book, you’ll start reading some sections sequentially and

interesting things happen – especially the first 300 pages, where you

see the actual birth of a profession.

Q: That’s some great stuff, and stuff I would never have read otherwise.

Lopate: Carl Sandburg was a critic – who knew?

Q: And he’s a really interesting film critic too.

Lopate: He really gets into it. He uses poetic devices to write film criticism.

Q: Has reading all this criticism impacted the way you write?

Lopate: I

don’t know if it’s changed anything but one thing is that it’s given me

much greater respect for working film critics. To be able to do it week

in and week out, and to have intelligent and well-constructed reviews

is impressive. When I was much younger, I would tend to reject film

critics whose taste was unlike mine. But now I see that someone like

John Simon or someone like Stanley Kaufman, who I don’t always agree

with, are really admirable in the way they can keep focusing on these

individual films, even if their tastes are different from mine.

Don’t feel like going back to the top? Click here to buy American Movie Critics from Amazon.