It’s pretty incredible to get the chance to interview Donald Sutherland, one of the all time greats, even once. But to do it twice – and just a few months apart? I feel so lucky I’m willing to give back all the big CHUD paychecks and do this job just for the love of it!

It’s pretty incredible to get the chance to interview Donald Sutherland, one of the all time greats, even once. But to do it twice – and just a few months apart? I feel so lucky I’m willing to give back all the big CHUD paychecks and do this job just for the love of it!

Hey, wait a second…

Anyway, I talked to Donald Sutherland at the Pride & Prejudice junket late last year. He wasn’t in the best of moods, and the table I was at was crowded with wieners. Also, he looked sort of like he had just come from getting commandments from the Lord. This time, though, Sutherland seemed to be in a great, talkative mood, and the table was almost empty, which means I wasn’t fighting to get in good questions while someone else wanted to ask about Kiefer. And he had shaved.

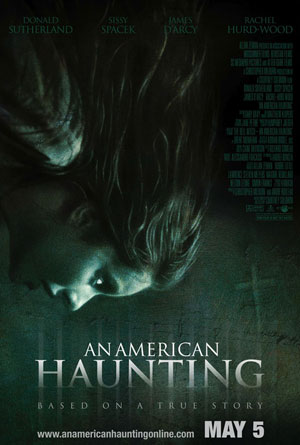

In An American Haunting Sutherland plays the head of the Bell family, a group of Tenesseeans in the early 1800s who are suddenly met with a very violent ghost in their house. It’s a role that Sutherland has fun with, and it turns out that the supernatural is something he’s very experienced in.

Q: Have you ever had any personal experiences with anything supernatural?

Sutherland: Yes.

[Pause]

Q: What would one of them be?

Sutherland: [laughs] Until about six years ago I lived with a ghost in the house we had in Quebec. When they sold it to us they said ‘There is a ghost in the house’ and we said OK. And we’re kind of ghost friendly; the idea didn’t terrify us. It was a little annoying because he was angry and he stomped around, he played the piano, and it got to the point of locking doors and taking the keys away. I don’t know how the ghost did it but the ghost opened the damn doors. We had two people who worked on the property, and the wife of the guy who lived downstairs and the ghost would come and sit on her bed because she had that kind of a personality – and she had been damaged in the same way the child in American Haunting had been damaged, in fact. Each of her sisters had been abused in the same way. She was a terrific woman and the ghost used to come sit on the side of the bed and talk to her. Not in an angry way. Decently.

We were drilling a well; they used to bring water up from a lake, but Laidlaw came and they brought waste up from the United States to a dumping ground in Canada, and despite all our protests and their promises it leached into the lake and contaminated it with mercury, and you could no longer drink the water or eat the fish from the lake. It’s kind of like Washington State where the Atomic Energy Commission promised that the waste from bombs from Nagasaki until today wouldn’t leak out, and of course it leaked out and it’s leaching day by day towards the Columbia River. We have destroyed our universe.

Anyway, the dowser came to do the well because it was difficult to find water on the property. After he said, ‘Listen go 235 feet here and you’ll have 20 gallons and go 50 feet here and you’ll have 30 gallons,’ – and we did, we went 235 feet and there were 20 gallons there -he came into the house and he was sitting there, he had a cup of tea, and he went, ‘You have a ghost.’ And I said yeah. He said ‘Do you want me to get rid of it?’ And we said ‘No no no… but! This room over here, the people who work in the house whenever they carry plates into that room, they break them. Plates fall out of their hands, cups fall out, we’ve lost a tea pot. We’re sure it’s him. Can you do anything about it?’ And he said, ‘Absolutely.’ He talked to it or whatever he did, but he said ‘Now its OK.’ And it was true. Nobody ever broke a plate in that room again. They broke it in the other room…somebody would go into another room and bang! We lost cutlery but then when the owner of the house died six years ago, the fellow who lived there originally, the ghost moved.

Q: Did anyone know who the ghost was?

Sutherland: His widow says it was his uncle. He was with the air force.

Q: You’ve done some classic horror films over the years. Is it a genre that you like to work in?

Sutherland: Nothing to do with genre. I don’t even think about it. The genre has to do with the director, it has nothing to do with the actor. Comedy has to do with the director. It’s just the reality of the character. You bring it in.

Nic Roeg changed my life; I’ve got a son named after him. He called me up – and this is back to you asking if I have any experience with the paranormal. I spent a lot of time, because I lived right next door to the Spiritualists Association in Great Britain, I used to go in and sit, I’d go upstairs and listen to séances. They had big brightly lit rooms and a bunch of people sitting in chairs like a lecture, except the lecturer was talking to somebody from somewhere else. It was extraordinary, and they told me a bunch of things that had input, that were fascinating, that made a difference in my life. And Nic Roeg sent me the script of Don’t Look Now and I liked it a lot. And I liked the two films he’d made, Walkabout and Performance, I liked them tremendously. I had this conversation with him, he was in England and I was in Florida. And he said, ‘Did you like the script,’ and I said ‘I like it a lot. I just think it’s incorrect to take extra sensory perception and use it as a vehicle for horror. I think if people experiences extra sensory perception they should react to it positively, I think that I should recognize what his fate is and save his life as a result of it; he shouldn’t be punished because he has extra sensory perception.’ And Nick said, quite succinctly, ‘Do you want to do the film or not?’

Nic Roeg changed my life; I’ve got a son named after him. He called me up – and this is back to you asking if I have any experience with the paranormal. I spent a lot of time, because I lived right next door to the Spiritualists Association in Great Britain, I used to go in and sit, I’d go upstairs and listen to séances. They had big brightly lit rooms and a bunch of people sitting in chairs like a lecture, except the lecturer was talking to somebody from somewhere else. It was extraordinary, and they told me a bunch of things that had input, that were fascinating, that made a difference in my life. And Nic Roeg sent me the script of Don’t Look Now and I liked it a lot. And I liked the two films he’d made, Walkabout and Performance, I liked them tremendously. I had this conversation with him, he was in England and I was in Florida. And he said, ‘Did you like the script,’ and I said ‘I like it a lot. I just think it’s incorrect to take extra sensory perception and use it as a vehicle for horror. I think if people experiences extra sensory perception they should react to it positively, I think that I should recognize what his fate is and save his life as a result of it; he shouldn’t be punished because he has extra sensory perception.’ And Nick said, quite succinctly, ‘Do you want to do the film or not?’

It was the first time I really came to terms with the fact that directors make movies. You go on stage, once you go out on stage its just you and the audience. The director can be waving his hands saying ‘Don’t say that you piece of shit’, but you can say it. There’s a certain autonomy you don’t have.

Q: Do you intend on doing any more stage work?

Sutherland: Maybe. I don’t intend to die tomorrow but I could.

Q: Do you miss the live audience? Having it be something new every night?

Sutherland: No. I was just thinking of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. He said being married to Elizabeth Taylor was like having a one night stand every night of your life. The only thing that really, really, really fascinates me is my marriage. I live with the most beautiful, extraordinary, hockingly intelligent, startling woman. Every day of my life is a new awakening. So I kind of do what she says. So if she wants me to go to the theater, I go to the theater. Because when we do do the theater she goes every night and comes backstage and she loves it. And I love doing it. But its really doing it for her.

Q: So what did she think of An American Haunting?

Sutherland: I had her fingernails in my wrist…she screamed and I do too. It’s scary. It makes me jump. They do things for real over there in Romania. When Rachel is dragged up the stairs, she’s dragged up the stairs. When the carriage went over, the carriage went over. ‘How are we going to do this?’ ‘Well, we’re going to run the carriage into a log. It’ll tip over.’ ‘But what about the people in it?’ ‘They’ll be OK.’

Q: Was there anything that you brought to this script, any input you gave Courtney?

Sutherland: Sure. I can’t remember what it was. But I do remember that Courtney sent me lots of information, and I sent him lots of information, and we had a very collaborative exchange. Sometimes I  would find things in my mouth that didn’t feel right in the continuity of what I had assumed the character to be, and we would try to pull that together and make it as real as we could.

would find things in my mouth that didn’t feel right in the continuity of what I had assumed the character to be, and we would try to pull that together and make it as real as we could.

Q: Were you familiar with the Bell Witch story before the film?

Sutherland: No. I don’t know much about America, to be truthful. I don’t know much about American history, I don’t, it’s interesting. I’m Canadian and educated in Canada, I spent most of my theatrical life in England. I try to catch up but there’s so much out.

Q: You’ve been in so many great comedies. Do you find that you’re not getting as many comedy scripts that you like, or you are they not coming to you at all? It seems like you haven’t done so many comedies lately.

Sutherland: No, you’re right. It just depends. I remember asking if I could audition for Same Time Next Year. They made a movie of it with Alan Alda. I asked if I could audition, and the producer said ‘Why? Does he do comedy?’

[Normally I wouldn’t run this next question, but Sutherland took this weirdly specific question about Kate Bush and spun it into this fascinating, weirdly specific thing about 1900, a great film]

Q: You were in Kate Bush’s Cloud Bursting video. How did you get involved with that?

Sutherland: She was such a stoner! She was great. She’d come out of this camper at 8 in the morning smoking a joint, and I said ‘What are you doing?’ And she said, ‘I haven’t been straight for eight years.’

I kept getting messages that she wanted to speak to me, and I didn’t want to know anything about it, and she found out from Julie Christie’s hairdresser where I was, at the Savoy I had a place in the back where I stayed, and she came and knocked on my door. When I opened the door, I’m tall, I didn’t see anybody. I looked down and there she was. And I said, ‘Why?’ And she said, ‘I want you to play Wilhelm Reich,’ and I said, ‘Oh Christ.’

You know, Wilhelm Reich’s The Mass Psychology of Fascism, I had a copy of it. You couldn’t put a copy of it anywhere, I had a print out copy of it in 1974, that I took with me to Bertolucci when I went to play Attila in Novecento, 1900. I wanted to make a fascist who, because of the bottom line of Reich, the second layer of psychology is fascistic. The second layer of ourselves is fascistic. I wanted to create a character who you  would look at and go, ‘But for the grace of God there go I,’ and Bertolucci wanted to be able to create a character that could hold a child by his feet and hit him against the side of a building and turn his head into a squashed pumpkin. Which is what we did.

would look at and go, ‘But for the grace of God there go I,’ and Bertolucci wanted to be able to create a character that could hold a child by his feet and hit him against the side of a building and turn his head into a squashed pumpkin. Which is what we did.

So it so profoundly impressed me that she wanted to do that that I adored her

Q: You talk about how the director makes the picture. You’ve worked with so many of the great directors over the years – Bertolucci, Fellini, Louis Malle, Pakula, Altman… when you’re working with a relative newcomer like Courtney Solomon, do you deal with him differently. Is there something different you bring to the set?

Sutherland: I bring something different to each set; it doesn’t have to do with their newness or their oldness. It has to do with the efforts to communicate with their spirit and the film that they want to make. That’s what you have to serve. You have to try to call out as much truth from yourself for the character. I don’t have anything to do with the film, I just have to provide a character that makes some sense to him, that will serve his purpose.

Q: Your character in this film, John Bell Sr – on one level he’s a good man, doing what he can for his family. On the other level it turns out he’s committed some horrible crimes against his daughter and his family. When you’re playing a character like that, how much do you have to understand where he’s coming from?

Sutherland: Completely. People find all sorts of justification for themselves. I know that he could give you arguments that could explain why it happened. There was a scene that was written that was much more explicit and covered his passion, desire, self contempt. Her almost Lolita-esque complicity. You must understand that even though there is a Lolita-esque complicity, it can never, ever, ever be allowed to exist, it can never be an excuse for anything, ever. Ever.

But the fact of it is, these are human beings, and they make compensation, they make adjustments, they continue to live. I’ve seen too many of those…one out of four, twenty five percent of the women in this country have experienced something of that order within a family. It’s devastating. The woman we spoke of in my house will tell you very clearly what she went through, what each of her sisters went through. But these relationships generally continue for a period of time. It’s not a one event as it turned out to be in this film. That was for some dramatic reason. It’s the director’s choice. The character submits to the inevitable punishment of that, because he knows what that poltergeist is doing. He knows why it’s doing it, in his heart of hearts. He wants to deny it and avoid it. You have a lot of people who lived through the Third Reich; you have people in denial all the time. How can we sit here and allow the Sudan, Darfur to happen? We turn a blind eye.

Q: Will you ever write an autobiography?

Sutherland: No. I can’t remember anything. I can remember jokes. I can remember thousands and thousands and thousands of jokes.

Q: I could use a good joke.

Sutherland: A good joke? Do you know the story of the guy who came running into the bar? He said, ‘Quick, give me ten martinis.’ The bartender pours out the martinis and the guys starts drinking – twothreefourfive! The bartender says, ‘Hang on a second. I wouldn’t drink them that fast if I were you.’ The guy says, ‘You would drink them this fast if you had what I have.’ The bartender says, ‘What do you have?’ He says, ‘Fifty cents.’