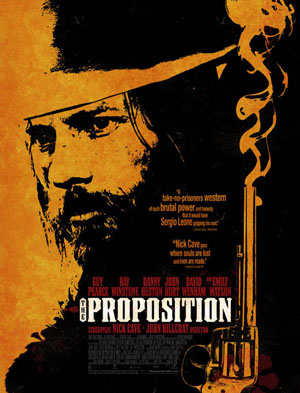

Written by Nick Cave, John Hillcoat’s The Proposition is a bleak story set in Australia’s early days, and in the untamed deserts that seem to be very analogous to the American West. Guy Pearce is an outlaw whose younger, soft brother is captured by the authorities and will be hung – unless Pearce finds his other, sociopathic brother and kills him.

Written by Nick Cave, John Hillcoat’s The Proposition is a bleak story set in Australia’s early days, and in the untamed deserts that seem to be very analogous to the American West. Guy Pearce is an outlaw whose younger, soft brother is captured by the authorities and will be hung – unless Pearce finds his other, sociopathic brother and kills him.

Hillcoat’s film is incredibly authentic-looking – almost oppressively so. Every frame is drenched in grime and blood and dust. But every now and again the director pulls back and shows us the immense glory of the Australian landscape. The Proposition has some of the darkest, nastiest shots I have seen in a while, but it also has some of the most beautiful. It’s a pretty wonderful visual contradiction.

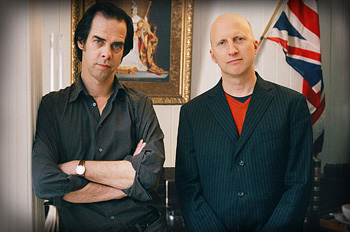

I talked to Hillcoat on the phone last week. The irony was that he was in New York and I was in LA – most of my phoners are vice versa. Hillcoat was a little beat, since it was 5pm New York time and he had been selling his movie all day. He managed to find some energy for me, though.

Q: One of the interesting things about approaching The Proposition as an American is that on a levels it looks and plays like an American Western. At the same time it’s very specifically Australian. Can you talk about what the modern Australian connection is to that particular part of your history?

Hillcoat: The one big difference is that we celebrate incompetence – Ned Kelly and Gallipoli. They ended in disaster. We have this tradition of supporting underdogs and the anti-hero while in America the tradition is much more celebrating victory and good against evil. Of course there’s the notable exception of – well, there was The Searchers – but certainly the anti-Westerns of the 70s had more complex views of the American West.

We’ve even come under criticism, and I think this sums up the difference between the two cultures – one of the criticisms that comes from America is that the script is fundamentally flawed because you can’t work out who is the good guy and who is the bad guy. I think it’s telling of the cultural difference.

Q: And it’s also telling of the culture’s approach to nation building, which is what the movie’s about, isn’t it? Hillcoat: And empire building. When Australians saw this film it had quite an impact because they hadn’t seen this part of their history told in this way. For them it was quite refreshing because it didn’t pull punches and it was matter of fact in terms of how harsh and brutal and racist all those things were. Australia tends to have a great deal of nostalgia about things as well, and burying their heads in sand. That’s sort of answering the second half, how do Australians view it.

Hillcoat: And empire building. When Australians saw this film it had quite an impact because they hadn’t seen this part of their history told in this way. For them it was quite refreshing because it didn’t pull punches and it was matter of fact in terms of how harsh and brutal and racist all those things were. Australia tends to have a great deal of nostalgia about things as well, and burying their heads in sand. That’s sort of answering the second half, how do Australians view it.

And there are parallels of nation building, where America is very much in that mode of empire and who the good guys are and who the bad guys are. I think that maybe that will strike a chord. But now I’m digressing.

Q: What is The Proposition saying about that? Is it saying that we need to kill our outlaws to move forward?

Hillcoat: Ooh. I wouldn’t say that. The thing is that I don’t think there’s a real sense of victory and progress. Certainly while Guy [Pearce] puts an end to something that he feels forced or impelled to do in a moral or ethical way, he’s also morally compromised by that action. I think that’s the important difference. When it comes to violence there is no clear cut winners and losers. The message I was hoping it kind of has is that the endless cycles of violence, how do you deal with that? And the futility of violence, how it keeps opening new wounds, and having old wounds that haven’t healed. The way that when it comes to these dilemmas, no one comes out unscathed. If this movie was shot in this country there would have been a much clearer sense of redemption and a stronger notion that everything’s fine and that he’s done the right thing and that it’s all going to move forward in an easy way.

Q: When you’re making a film about the futility of violence and you’re showing so much violence, how do you keep from crossing the line and making it thrilling? It’s so easy to glamorize violence in film.

Hillcoat: It comes down to restraint. Ironically there’s more attention paid to the violence in this film than in an average Hollywood film which makes it a thrilling rollercoaster ride. We very much explore the consequences of the violence so that you see the physical, psychological and moral aftermath of that violence, instead of the comic book thing which is increasingly popular in mainstream cinema.

Most of the big violent events in this story are offscreen. It was a conscious decision to not use any slow motion, to have it very quick and confusing and surprising and shocking. A sudden disorientating eruption. I’ve analyzed in great detail how violence affects people in the media, how we view violence. I think the key is actually pulling away. If you want to really analyze it, when Charlie’s speared you pull away from the event, big and wide. Conventionally, dramatically, you would approach that very differently. I’ve unfortunately witnessed real violence, and it’s so fast and disorientating, and that’s something I wanted to convey.

witnessed real violence, and it’s so fast and disorientating, and that’s something I wanted to convey.

But there’s something so seductive. There’s the contradiction that Peckinpah explored – there is a thrill and an attraction to violence that’s also repulsive and repellant and disturbing. I didn’t want to go down that path because it’s been done so brilliantly by other filmmakers like Peckinpah. Apocalypse Now, the great power of that film is that it shows the seduction of destruction and war as opposed to the anti-war message.

I wanted to do it in a matter of fact way. Film is so seductive and powerful that you can easily get carried away and seduced. It’s all about restraint.

Q: It’s been a while between projects for you.

Hillcoat: I’ve had a hard time in this business. I’ve made three films in roughly seven years apart each one.

Q: I imagine that with The Proposition things will get easier. It was a big hit for you back home.

Hillcoat: It certainly hit a nerve with audiences and critics, which will make life easier. The great thing is that I’m confident I’ll be able to make more films. Q: Do you have another film lined up?

Q: Do you have another film lined up?

Hillcoat: Nick’s written me another one. We’re hopefully going in autumn on that.

Q: And what’s that about?

Hillcoat: It’s contemporary. It’s very different. It was written for Ray Winstone. I’m terrible with pitches and descriptions, but it’s a very personal and emotional little film. I’m also looking to do something here. I’m basically looking to work more regularly, to make more movies.