This review contains minor, unavoidable spoilers.

This review contains minor, unavoidable spoilers.

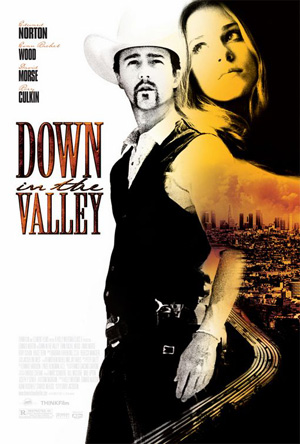

Los Angeles is a weird place, and if you don’t know that firsthand, the movies are always willing to tell you. Hollywood loves turning out movies about itself and its immediate environs, and it’s rare when one of those are really of interest to anyone outside that community. The ones that work the best are those that find something LA has in common with the rest of the country as opposed to something that makes it bizarre, weird or wacky. Down in the Valley is one of those films; while it’s very specifically about Los Angeles’ tacky San Fernando Valley, the themes of the mythology of personal reinvention and a muddled connection with history feel very American. Also, Edward Norton plays another crazy person.

Crazy maybe isn’t the right word. Self-deluded works pretty well – Norton plays a young man who has created a complete persona around himself. He’s a cowboy, an aw-shucks ranch hand from the Badlands. He wears cowboy hats and boots and takes his new girlfriend line dancing. But he’s not what he seems to be, and he’s not from as far away as he claims. Harlan is the quintessential Norton character – two people living in the same body. In this case one is filled with nostalgia for a fantasy past he has never actually experienced and the other is a dangerously on the edge loser. Norton’s done the role before, in Primal Fear and Fight Club, and Down in the Valley is a further refining of the concept. The reveal here is less stunning than in the two previous films, but the artistry Norton brings to it is just as impressive. No other modern actor has the ability to be two competing characters at once; when he’s drawling as Cowboy Harlan, Norton still shows us that other hidden Harlan.

It’s Cowboy Harlan that Evan Rachel Wood’s Tobe falls in love with. They have a meet cute at a gas station, where he’s working. She offers to take him to the beach with her friends and they fall in love. Tobe’s dad, a corrections officer played by the great David Morse, isn’t sure he likes this cowpoke dating his daughter (and who can blame him? Norton is in his mid-30s while Tobe’s character is established as being in high school. I have to assume that Norton is playing 15 years younger, but there’s no specific indication of it. I kept waiting for Morse to even mention the fact that Harlan has a decade on his daughter, but he never does. It’s a distraction). He becomes even unhappier when Harlan starts taking an interest (non-sexual) in Tobe’s adopted younger brother, who has some never defined emotional problems.

The relationship between Tobe and Harlan is the center of the film for the first act or two, but the real relationship ends up being between Harlan and the young Lonnie, played by Rory Culkin. What is it about Lonnie that attracts Harlan? Writer/director David Jacobson keeps the exact details of Harlan’s past unclear, although at one point he does deliver a speech about foster care that indicates he’s been through the system. How much can we take what Harlan says at face value, though? It’s one of the delicious dilemmas the film offers us.

It also offers us shifting sympathies, something rare in film today. You begin the movie strongly disliking Morse’s character, but by the end it’s hard not to side with him. Along the way your feelings about Harlan are all over the map; in a lot of ways he reminds me of Travis Bickle (surely a comparison I’m meant to draw, as Harlan has some very Travis-like scenes in front of a mirror), where you’re never sure how much you’re supposed to like this guy. Harlan’s a toxic event in cowboy boots, but it’s hard to deny his bizarre sincerity. Even when he’s outright lying you wonder if he doesn’t believe everything he’s saying. And is a lie still a lie when the liar believes it?

Tobe’s the Valley of today, while Harlan’s the romanticized vision of the Valley – or really less specifically, the West – of the past. It’s easy to drive around parts of Los Angeles and see the desert scrubland as it must have been a hundred years ago, before the East Coast Jewish movie moguls fled out West to avoid Edison’s motion picture copyrights (and their faith ends up being very important to this film, as a key to Harlan’s relationship with his past and the past of the city). But over each hill is a strip mall filled with more and more hamburger chains. Of course the phenomenon isn’t just in LA – you can go anywhere in America and often feel like you’ve never left home because of the mass homogenization. This is what Harlan’s trying to opt out of, and who can blame him for that?

But the opt out is doomed. Is it because of Harlan’s own personal demons? Partially. But the film’s third act, which at times turns into a long chase scene populated only by symbolism, argues the inevitable victory of pre-fab homes on anonymous suburban streets. On some levels I think I may find more truth in Harlan’s search for another way than Jacobson does – the character finds succor on a movie set where a period Western is being filmed, and Jacobson makes him a ridiculous figure, easily awed by artifice.

Jacobson’s come a long way since his last film, Dahmer. Down in the Valley is, in very many ways, a wonderful throwback to 70s era filmmaking, especially in the way Jacobson allows the film to slowly build. He’s not worried about the ADD viewing habit of the Tobes in the audience, and he often fills his frame with the languorous, early afternoon feel of the scrublands. The film is as expansive as the landscape, but never dull. The actors bring naturalistic vitality to their roles, especially Evan Rachel Wood, who makes the transition from tween to adult without missing a step, and that’s not even taking into account her hot sex scenes with Norton. And while Wood and Norton get the showy, big parts, Culkin brings touching vulnerability to his scenes, many of which don’t give him many lines, and Morse is a phenomenon as the angry, confused father.

Down in the Valley is a rich, engaging movie that’s slightly let down by some of its third act shenanigans. It’s an exciting film, especially in a year that offers soggy, idiotic big picture spectacle for as far as the eye can see. It’s always nice to see Norton come back to the screen to show us what he can do, and to remind us that he’s a serious contender for the title of our greatest modern actor, and now I’ll be looking forward to what Jacobson gets going next. With this film he’s announced himself as a major talent with something to say.