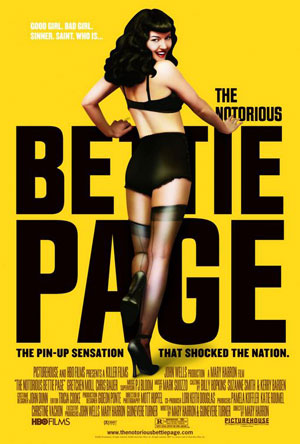

The Notorious Bettie Page isn’t a bad film, I just don’t understand why it exists. It’s a biopic that focuses on a time of the subject’s life mostly devoid of interesting conflict and it’s an examination of sexual subgroup that seems to have no actual interest in that subgroup. Perhaps most strange of all is that The Notorious Bettie Page is the latest entry in the “politically conscious” genre yet it seems to have no actual consciousness when it comes to politics.

The Notorious Bettie Page isn’t a bad film, I just don’t understand why it exists. It’s a biopic that focuses on a time of the subject’s life mostly devoid of interesting conflict and it’s an examination of sexual subgroup that seems to have no actual interest in that subgroup. Perhaps most strange of all is that The Notorious Bettie Page is the latest entry in the “politically conscious” genre yet it seems to have no actual consciousness when it comes to politics.

Bettie Page is easily the most famous fetish model of all time – she all but defined a look that still exists to this day. Walk into most salons and ask for a Bettie Page hairdo and they’ll know what you’re talking about. Page’s specialty was bondage, mostly the lighter stuff. After a couple of years of prominence, or what passed for prominence in the fetish modeling scene of the 50s, including a Playboy shoot, Page disappeared. Her cult grew stronger, and exploded with the advent of the internet, when people could easily see even the rarest of Bettie’s pictures.

Why was she so popular? Don’t ask Mary Harron, the director of – she doesn’t seem interested in this aspect of Page. She seems barely interested in the world of fetish fans at all. The movie simply explains that these people exist, but no one ever really gives a thought as to why, to what needs these pictures were fulfilling for these men in that quintessentially repressed time. On some level I can deal with this omission – the movie seems to argue that Page didn’t really care, so why should we – but I was endlessly frustrated with how the film glossed over her popularity. One of the toughest things a biopic of a cult figure must do is explain to the audience why this person is worth paying attention to; when the movie is about a model the problem is doubled. Page’s appeal was based on her looks, and short of finding a clone, Harron couldn’t possibly just replicate that onscreen as easily as The Notorious Bettie PageWalk the Line allowed us to hear Johnny Cash’s songs. So rather than figure out how to address the issue, Harron seems to avoid it.

There’s some hint as to why the photographers liked her. Page is innocent in a non-naïve way, and she seems to have fun in the photo sessions. We don’t get a chance to see what many other photo sessions are like, though, so there aren’t a lot of points of comparison, except what we bring into the theater with us.

But where the movie drops the ball is in how it weirdly focuses on a section of Page’s life when not that much was going on. She was raised religious, and the first part of the first act of the film bring us through some of the traumas that may have made her the person she became – sexual abuse at the hands of her father, physical abuse at the hands of her first husband, a gang rape – but this stuff is over pretty quickly. We’re soon in New York City with Bettie, getting in on the modeling game and slowly becoming successful. And then the movie ends. Well, first she returns to the church in the film’s final minutes, but it’s incredibly unsatisfying, dramatically. Here’s this life book-ended in religion and filled in the middle with sin – why not examine this more? It’s there, in passing, but like so many of the other things that make Bettie interesting, it’s glossed over.

I think that a major mistake the film makes is to accept Bettie’s feelings on things. It seems as though Bettie doesn’t think about the strange dichotomy of her life, so the film doesn’t either. In this case the unexamined life is not worth biopicing – I appreciate the desire to keep the story from Bettie’s point of view, but the movie is already book-ended with a Senate hearing on pornography that Bettie was called for but never testified at. That hearing could have been our in to the wider world of porn and bondage, and perhaps offered an interesting counterpoint to the almost insanely rosy view of the subject the rest of the movie has.

As someone who rabidly defends free speech and who believes porn is essentially harmless (on the consumer, in reasonable doses) it’s weird to write that, but the truth is that part of our cinematic interest in porn is the exploitational angle. Harron’s films approach their subjects without judgment; while this worked in I Shot Andy Warhol and American Psycho, here it comes up slack. There’s a scene in the film where Bettie’s second husband discovers she’s doing bondage pics in addition to normal cheesecake stuff and he’s horrified. I couldn’t blame him; I kept wanting to tell the movie that it was dabbling in a seedy, weird world. The movie kept ignoring this.

Gretchen Mol is Bettie Page, and while the performance isn’t bad, it is bland. Harron needed to find an actress who could get across something heavier than sheer vacancy, and that’s often beyond Mol. The script intimates that Bettie’s smarter than she lets on, but the performance indicates quite the opposite. For those of you who are truly depraved and keeping score, yes Mol does get some full-frontal nudity in, but I am guessing she wore a merkin. Surely this should be my Rotten Tomatoes pull quote.

Much more interesting are the supporting pornographers – Lili Taylor is exceptional as Paula Klaw, the woman who, along with her brother Irving, ran a mail order fetish photo business. These people are fascinating, as is Jared Harris as John Willie, the bizarre and besotted photographer. These are characters, but they come in and out of the film too quickly. David Straitharn also makes an appearance, playing Estes Kefauver in the wraparound Senate hearing sections. Movie nerds may know Kefauver best for harassing the mob in the Godfather Part II. Straitharn’s appearance frankly feels more like deleted scenes from Good Night, and Good Luck were spliced into the film.

The Notorious Bettie Page lacks any real depth, and ends up glossing over the life of its subject. It’s very possible that the subject just doesn’t deserve a biopic, that quite possibly Bettie Page’s impact on the popular culture is more interesting than how she made that impact.