David Slade does not talk, he holds forth. The press at the New York junket for his directorial debut, Hard Candy, was almost superfluous, since I think Slade would have gone on to make this same points to a room that was empty except for some recording devices. I can tell you already that there will be no dead air on the Hard Candy DVD commentary.

David Slade does not talk, he holds forth. The press at the New York junket for his directorial debut, Hard Candy, was almost superfluous, since I think Slade would have gone on to make this same points to a room that was empty except for some recording devices. I can tell you already that there will be no dead air on the Hard Candy DVD commentary.

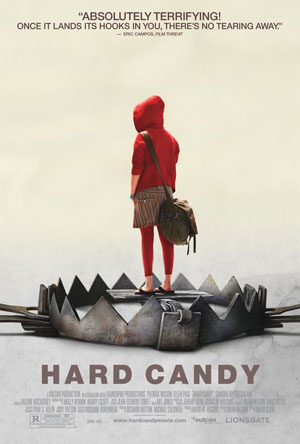

Hard Candy is a tense, emotionally disturbing film – it’s a psychological thriller in creepy overdrive. It’s a small piece, essentially a two-hander set in one location. The fact that it works so well is a testament to the skills and talents of the actors and the director whose steady eye creates the tension and dread that’s so palpable throughout. And it’s a film that sets up tough moral questions – a 32-year old man (Patrick Kohlver) meets a 14-year old girl (ELlen Page, Shadowcat in the upcoming X3) online and brings her home, only to find the tables turned and the girl all too ready to torture him for his creepy ways.

Hard Candy opens this weekend. Look for more Hard Candy coverage – including an interview with star Ellen Page and an exclusive clip – later this week.

Q: How did you find Ellen Page?

Slade: We saw three hundred girls who read. They did two very disparate scenes in the film. There were a few that were good, and a few that have gone on to become famous, but nobody really understood the role completely. The casting director showed us this tape of [Ellen] and she was just phenomenal. Her acting was above and beyond all the adults she was around, and she was much younger then. She was sent the script and she really loved it; she was really passionate about it. What she did is that she read for us up in Canada, on videotape. But what they didn’t tell us is that she just finished this film, Mouth to Mouth, which is very good and coming out later this year, and she had shaved her for the role.

With it being such a delicate subject matter there was a certain amount of nervousness for our producers, because she looked quite young. And she looked like a boy, because she had no hair at the time. So she did it again with this wig on, and she still gave this phenomenal performance. We talked to her on the phone and we were even more convinced. The main producer, David Higgins, whose initial concept this was, whose kind of seed of an idea was given to Brian Nelson and I, flew Ellen to LA so that she could be in the room with the financiers. We talked through the scenes, she went to rehearse them and came in and knocked everybody away. It was one of those situations where I said so much about this girl that I couldn’t say anything when she came in, but she did it all on her own. In fact one of the things that was said by one of our financiers was – because I wanted them to understand how intelligent Ellen is. I wanted them to know that as well, which is a very important part of not only performing but of being the person, being ready for any eventuality. More important for going through this role and getting out the other side of it, and living life afterwards unchanged, which is a huge moral part of when you’re casting. So one of the people said, “What person in history does this character remind you of?” And she said, “Joan of Arc.” And she got the role. And that’s the story of how we found Ellen and took her from Canada and come down. And of course she’s gone on to greatness.

Q: Were you ever concerned that you would lose audience members by having this young girl do these horrible things?

Slade: Never. The piece as written is largely about responsibility. That’s the text. It was a piece about taking responsibility for your actions, if you want to sum it up in a line. Not about all the other things that come with it, but more here you have a man who is clearly guilty from the word go – he’s taken a 14 year old girl home. Guilty. Then you go through this process of examining each and every one of the moral lines that we all have set by society. We examine, each of them. And we challenge them, each of them. There was never a concern because I knew we weren’t going to shoot this film in a way that’s exploitational. This thing was storyboarded almost six months before it was shot. It was done very meticulously as a piece of filmmaking craft. There was never a concern that we would be lewd or that we would be inappropriate, ever. We don’t show images that are lewd or inappropriate. But once the audience gets to a stage where they are comfortable we make them uncomfortable.

When you’re doing a piece about responsibility, you have to be responsible, and I feel responsible. I’m trying to look from someone else’s shoes at why you would feel uncomfortable about this. Ellen was 17 when we shot, playing 14 – she was very mature, very confident in her abilities. We had a week of rehearsals and we blocked everything out and we really felt on solid ground. I am trying to address the question and think what it might be, but I can’t think of anything. We felt on morally steady ground.

Q: It’s by far the best looking digital film I’ve seen.

Slade: It’s not a digital movie. That’s why! We went through an extensive digital post process, but we shot on film. Some website somewhere published something like this and it’s come back a few times.

No, we shot film. Let me address that: this is a film made for under a million dollars. I can tell you for a fact that it was because lost our bond company and our financiers had to come in with the bond money. We came in under budget and didn’t actually have to spend it. So I know we were x amount under a million dollars. Often when you hear that a movie cost a million dollars that means the studio picked it up in a certain state and finished it off – actually we delivered was a negative that was ready to make theatrical prints from. We really had under a million dollar budget.

The reason we were able to do this was the passion of all involved. The cinematography, every single department, which I had known since I had done over the years – not many but over the years I have done selective music videos and commercials. Let me qualify that and say I’ve never met a choreographer – I work with bands, larger more obscure than you’ve ever heard of. I think the most famous person I ever worked with was Tori Amos. I have been lucky to do videos that enhance my filmmaking abilities. I have always been hand to mouth through that industry. And I did a few commercials here that have paid for things. They always had great scripts – I could get a bit of money but they had great scripts. One of the things that happen very quickly is that people go, ‘Oh he’s a video director!’ and think it’s all style and no substance. I was very aware of that going into this film, that the style of the film had to be a very specific vocabulary with very specific rules that weren’t there to be stylistic but were there to stem from character.

Q: Can you talk about your decision to use a lot of very tight close ups in the film?

Slade: I believe there is a DNA to the filmmaking of suspense or horror, which is different from that of an action film or a comedy. If you understand those things, they force you to make those choices. Those choices are made for you. If you are adept with your craft, and you understand your camera and the lens size and what that will do and you understand the emotion you want to create coming into a scene, it comes to you.

A lot of this film was about one or two things: isolating the focus so that the audience can’t see more than we show you, which gives a sense of claustrophobia but also focuses you, because you can’t look at anything else. You have to listen to the very complex information. I would like to talk a bit about Brian Nelson tangentially, because it’s relevant. Brian Nelson, the writer, one of the things he does fantastically is put really complex arguments into really simple words. But they’re really complex arguments, so if you’re seeing six things at once, you’re not going to hear those arguments. A lot of times I said, we’re just going to stay here so we just hear what the person has to say. It’s very important at this time that we see nothing more than the performance. So isolating the field of view was part of that. Also the language of suspense and withholding information necessitated those choices – a shallow depth of field where you don’t know what could possibly be… once you get rolling with those choices you can then get to a point where the audience gets complacent with this, where they don’t think they’re going to see anything, so I’ll show them something nasty, because that way they’ll go back on edge again. Or OK, we’ve all seen the point of view shot used in horror films – I’ll give you three, four points of view so that you don’t know where the hell anyone is. So that you’re completely disorientated.

I spent ten years learning my craft to the point of which I can work my own thought processes on set, but where it’s also meticulously designed. To the point where a year in advance I told the financiers that there’s hardly going to be any wide shots in the film – that’s the only way we can do this. And they said, OK, fine, and a year later of course when we’re cutting they said, ‘Where are all the wide shots?!’ There aren’t any. ‘But there must be some more!’ No, I told you a year ago. ‘But that was a year ago!’

Q: I want to follow up on the digital aspect – your palette is very carefully constructed, and this is the only movie where I’ve seen a digital colorist in the opening credits.

Slade: One of the anxieties as a director is that you’ve got two people in a house for a whole movie, so you design into it a texture. Now one of the things that was a ‘Should I do this or should I not’ came down to the performances of the actors. If the performances of the actors were not convincing I think you would see those colors really clearly as colors. Now I believe most people watch this film and feel those colors rather than see them because the performances are so strong. The degree as to how expressionistic I could be as a director was determined by how realistic they were as actors – meaning the more convincing they were, the more transparent the form between the viewer and the performances were, so you could do more. You could do much more and you could go much further, and in so doing enhance emotionally what’s happening on screen.

We designed specifically a digital color process, which is titled in the opening credits. So much of the atmosphere of this film comes from the color and sound design – sound is something else that is used exclusively.

Q: Do you think people will have a hard time figuring out who to root for?

Slade: You take into the cinema, I think, very much what you walk away with. Although the characters in the film may preach, it was very much written not to preach to you. It was a film which was not designed to take a point of view. Which is not to say that we’re morally bulletproof. Of course we’re not, and nothing is. There is a preferred reading of this material, but we were very careful not to be preachy in this film. Hailey, the character, is a 14 year old girl, and at 14 her view of the world is very black and white. This is part of her character, she is not someone who has filled in the levels of grey. Therefore the decisions she makes is very hard and concrete. She is filled with the hormones and the passions of someone of that age, and therefore she’s empowered by that, making these clear, solid decisions. Yes, she may have moments of anxiety where things don’t go to plan, but like the urban myth where the mother can lift the car off the child, she has that kind of power because her friend was killed. She is going to do what she believes is right because she’s 14 – not because of any moral stigma or anything that’s dictating this, but because she’s 14 and why the hell not.

The questions that should be leveled clearly are at the character of Jeff, who is 32. What becomes interesting is where the audience begins to side with Jeff. I’ve heard there have been screenings where the audiences have a response that makes it very clear that they’ve sided with Jeff. You’re like, OK, wait until you get to the end of this, you’re going to have some questions about yourself. As I did when I read the script, which is why I wanted to make this film. When you get to the end of this film if you’re a man you end up having to ask yourself questions. The film is about getting people to ask those questions more than it was about – you know, we did this two years ago before all the recent press that is quite timely that has to do with the text, not the subtext, of the film came about.

Q: This is a very talky, house-bound film. Your next movie, the adaptation of 30 Days of Night, is that going to be a big change up? Will it be more action oriented? And are you trying to replicate the artwork of Ben Templesmith?

Slade: Brian Nelson’s writing the script, so that means we have a very original take on the genre. Indeed I don’t believe there’s much of the genre left in what we’ve written. Still, it’s very faithful to Steve Niles’ writing and the town and the aesthetic. We hope at this point – we don’t start shooting until this summer – that we’re going to be very close to Ben Templesmith’s artwork. We’re going to maintain a level of realism.

Q: Are you going to shoot in Alaska?

Slade: We’re going to shoot sections in Alaska and sections in New Zealand.