Blue Beetle is dead, long live the Blue Beetle!

By Graig

Ted Kord was like a beloved uncled to me. A goofy beloved uncle who’d stop by from time to time, make me smile and be on his way. Ted knew how to make me smile… he knew how to make everyone smile. Though he acted the buffoon, he didn’t joke his way into a highly successful high-tech enterprise, you know. He was a virtual genius who just happened to have a sense of humor and a sense of adventure and a sense of justice. It’s not just anyone they let into the Justice League you know.

Ted Kord was like a beloved uncled to me. A goofy beloved uncle who’d stop by from time to time, make me smile and be on his way. Ted knew how to make me smile… he knew how to make everyone smile. Though he acted the buffoon, he didn’t joke his way into a highly successful high-tech enterprise, you know. He was a virtual genius who just happened to have a sense of humor and a sense of adventure and a sense of justice. It’s not just anyone they let into the Justice League you know.

Stupid Max Lord shot him in the face. And it was nothing like when Vinnie Vega shot Marvin in the face in Pulp Fiction. Nope, there was no bump. Ol’ uncle Ted figured out Max’s demented secret on his own (because he was smart, see), and his payment was a bullet through the eyeball. Ted’s dead, baby. Ted’s dead.

So then what’s up with this Blue Beetle everyone’s talking about? If not Ted, then who? Well, if you missed Infinite Crisis and Day of Vengeance and all that stuff (and a big “oh well, didn’t miss much” if you did) don’t worry, because our friends Keith and John (you can call them Mr. Giffen and Mr. Rogers) have laid it all out for you here in the first issue of the new, Kordless Blue Beetle series.

Taking place almost immediately after the now incredibly late finale of Infinite Crisis, we find the new Blue Beetle in a tussle with a freaked out Guy Gardner. This Blue Beetle looks very little like the old Blue Beetle, since he’s all techno-armoured and stuff. In flashback we meet Jaime and his school chums Brenda and Paco. As they’re horsing around, Jaime finds a stone scarab in the dirt. A little while later, when Jaime’s asleep the scarab comes alive and embeds itself on Jaime’s spine. Jamie awakens with a start to hear himself speaking a language he can’t identify, and more bizarre things begin to happen in his life, leading to a few months later a rather puzzling encounter with a certain bowl-cut redheaded Green Lantern.

Yeah, this kid isn’t Ted. I get that, but Misters Giffen and Rogers have rapidly established a new reluctant teenaged superhero (in the Spider-man vein), a fun supporting cast in both friends and family (the brother-sister dynamic is spot-on), and a damn cool new interpretation of an old character. Cully Hamner, finally back on a regular series for the first time in what seems like forever, has designed a really, really, really neat looking Blue Beetle. He’s taken elements of the old costume and teched them up times ten, without being bulky and gaudy. Even with the giant scarab backpack somehow it doesn’t look goofy, it just looks amazing. And when we get a sampling of the Beetle’s new powers I was both wowed and intrigued. I need an action figure, STAT!

I’m witnessing something special here, a tightly written, accessable, well illustrated, cleverly designed, intelligently characterized and, above all, fun comic book. There’s not enough books like these, but I’m glad there’s this one. I’m glad there’s a Blue Beetle.

RATING:

First Look: Charlie Huston and David Finch Plan on White After Labor Day with “Moon Knight”

By Russell Paulette

There are some characters that you know you like before you know anything about them—it’s a look, a costume design, a character name. Something about them, at first flush, just strikes you in the right way, and Moon Knight has always been that sort of character for me. Sure, I picked up the Essential Moon Knight trade paperback the other week, but there it sits on the top of my teetering to-read pile, threatening to wash over me in a four-color landslide. So, I figured next week’s relaunched series, with novelist Charlie Huston and superstar artist David “New Avengers did wonders for my bank balance” Finch at the helm, was as good a time as any to familiarize myself with this latest iteration.

There are some characters that you know you like before you know anything about them—it’s a look, a costume design, a character name. Something about them, at first flush, just strikes you in the right way, and Moon Knight has always been that sort of character for me. Sure, I picked up the Essential Moon Knight trade paperback the other week, but there it sits on the top of my teetering to-read pile, threatening to wash over me in a four-color landslide. So, I figured next week’s relaunched series, with novelist Charlie Huston and superstar artist David “New Avengers did wonders for my bank balance” Finch at the helm, was as good a time as any to familiarize myself with this latest iteration.

Immediately, Huston sets the tone and swagger of the book and its title character with some deft storytelling. We know that this guy is one of the street-level heroes and he loves the work—all the dirty work, the fisticuffs with thugs while the big guns go off and save the universe. We learn of his place in the scheme of things, his former role as an Avenger, his pilot buddy, Frenchie, as well as his unusual methods of worship, which center on the Egyptian god, Konshu. Huston delivers all of this in a terse narration–a stripped down, bare-knuckled, hard-boiled voice that’s overlayed over a standard hero-kicks-ass pre-credit set-piece. The issue turns in the middle, revealing a haunted Marc Spector, Moon Knight’s alter-ego, staring out the empty end of a bottle while wheelchair bound, desolate. As Huston transitions to this scene, he delivers staccato cuts of flashbacks, giving us a taste the sins that wore this hero down. Quick, dirty, but doing the job to establish his narrative, Huston mainly delivers groundwork here, setting us in the right psychological and narrative frame-of-reference for whatever he has in store.

On point here, though, is David Finch’s artwork. Though still suffering from many of the faults that have plagued him much of his career—his tendency to over-render textures, and an occasional framing blunder that leads to blunted storytelling—this artwork shows a sharpness and panache that we haven’t seen from Finch in quite awhile. He’s mastering his own style, one that’s developed far from the Silvestri/Top Cow mold that he broke onto the scene with. His storytelling, too, has been improved by his time at Marvel, showing a confidence in letting moments happen, and holding the audience with large areas of black, blank space. It’s not perfect, but it’s definitely improving, and for the better.

A more-than-decent introduction, these two creators seem like they’re arriving at this book with a shared enthusiasm that shines through each page. Huston’s scripting is lean, taut and precise in a way that’s often surprising from crossover writers (insert your least favorite here), and he seems to have an intuitive sense of when to step back and let the artist propel the narrative–which, for his part, Finch is ably meeting expectation. Where the issue lacks, perhaps, is in its narrative drive—it’s merely a simple set-up and that’s all. There was a psychological tooth to the first issue, but no sense of purpose or direction. An interesting character piece, but one that, when you come down to it, consists of two scenes, one that’s all action, the other, all character. Not a bad read, by any stretch, but one that leaves you hoping the plot kicks into high gear, and soon.

RATING:

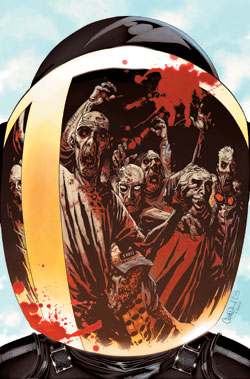

A Return to Form for Kirkman (Part I: “Walking Dead” Edition)

By Mark Wheaton

“I was never out there. I was never in danger, hunted, terrorized by those things. I was in here before they came to life and started killing people…and I was in here after. So yeah – it’s a new world, but God help me, I like this world better.”

“I was never out there. I was never in danger, hunted, terrorized by those things. I was in here before they came to life and started killing people…and I was in here after. So yeah – it’s a new world, but God help me, I like this world better.”

Just as the limited edition hardcover collection of Walking Dead hit the comic shops last year, the monthly run of the post-Apocalyptic series began to falter. As Kirkman impressed a new wave of fans with the darkly comic Marvel Zombies, his other zombie book became more and more of a soap opera exploring character relationships and locking down who would make up the survivors – the now self-described “walking dead” – going forward.

That’s all well and good, but three issues ago when a helicopter appeared pulling a few of the group away from the action-stunting prison, a much-welcome return to zombie-kicking action appeared to be on the horizon. With the words:

“DOWN ON YOUR STOMACHS—NOW!! WE DON”T WANT TO SHOOT YOU BY ACCIDENT!”

– followed by a barrage of gunfire that decimates a group of “biters,” that prophecy comes to fruition.

Rick, Glenn and Michonne go out to discover what happened to the crashed helicopter and find that any survivors had already been carted off by what appear to be other survivors. They follow the trail to nearby Woodbury where they meet the militarist residents who have created their own Land of the Dead-esque fortress against the zombies. Though it looks fine on the outside, Rick knows enough to immediately lie and say they’re the only ones traveling together.

Unfortunately for our heroes, the “governor” of the four blocks of reclaimed territory turns out to be a bad guy (but only in the final panel, cliffhanger reveal). Maybe. The governor and his boys run a “Planet Hulk”-style gladiatorial combat arena that pits slave-collared zombies against strangers (speaking of Land of the Dead…). Rick, Glenn and Michonne fit the “strangers” label, so you can figure what issue #28 will entail.

Like 100 Bullets, Walking Dead is getting to the point where waiting until trade paperback might be an easier way to follow character development instead of constantly going back a few books every month to remind the reader of the serpentine relationships that are going on with the survivors. That said, the plot of #27 makes it look like Dead is moving back into exploring the world outside of the prison (even talking about ‘what happened’ for a couple of sentences when the governor mentions the failure of the National Guard to contain the zombies during the initial outbreak), which was always the strength of the comic.

Hopefully, the current run of Walking Dead will prove to be the start of another great arc.

RATING:

A Return to Form for Kirkman (Part II: “Invincible” Edition)

By Mark Wheaton

“Holy smokes – you’re back and you’ve gone just a bit gay.”

“Holy smokes – you’re back and you’ve gone just a bit gay.”

Mark returning to Earth is a good thing. The look on his mother’s face when she sees him for the first time in over a month is pretty great, but that’s nothing compared to her reaction when she hears Mark’s new little brother speak his first word in her house: “Brother.”

Though Mark/Invincible’s recent adventures in deep space have made for an entertaining arc, he left so many things undone back on Earth – his mother’s crumbling into alcoholism, his new relationship with Amber which may or may not be a really bad idea, his budding rebellion from Pentagon-control, etc. – that the next few issues may well be pretty fascinating.

Invincible works best when it takes the conventions of the superhero genre and turns them on their collective heads, relating the experiences of this young kid coming into his own – a’la Peter Parker – as the superhero son of the most powerful Superman knock-off in comics, who he subsequently learns is a villain. While visiting other planets expands the comic’s universe to cosmic levels, the grounding in school-day reality is one of the title’s strengths. So, when Mark headed off-world for a few issues, it took away from the very reality the comic’s first couple of years strove to establish, like Homer Simpson now missing endless days of work at the nuclear plant for the sake of expanding into surreal Simpsons adventures.

But change is afoot. Throughout the first thirty issues, Mark’s relationship with his Global Defense Agency minder Cecil Stedman has been relatively friendly – a surrogate father who hasn’t turned him wrong. But now, like Nick Fury’s relationship with the title character of Ultimate Spider-Man, Mark is starting to see the differences between himself and Cecil more clearly and his national responsibilities aren’t as appealing to him as they once were. Obviously, this matter will soon come to a head.

Like Walking Dead #27, Invincible #30 has writer Robert Kirkman laying the groundwork for the rest of the year with what could potentially be some seismic changes to the title’s world, though hopefully some of the humor of Invincible’s first twenty-nine issues may return as well.

On a side note, the preview of the Nextwave-esque Capes at the end of the issue was hilarious.

RATING:

Star-Spangled Fun: The Captain America 65th Anniversary Special

By Jeb D.

When this title was first announced, I was expecting some kind of decades-spanning reprint collection, with maybe a bit of new material (along the lines of Marvel’s recent “Giant-Size” titles). After learning it would be a single oversize Ed Brubaker story, I assumed it would be something quietly reflective of Cap’s career (like Brubaker’s Cap House of M story). What I hadn’t expected was a cracking good WW2-era Captain America adventure, guest starring Nick Fury and his Howling Commandoes (‘bout time!), and dovetailing nicely into Brubaker’s current run on Cap.

When this title was first announced, I was expecting some kind of decades-spanning reprint collection, with maybe a bit of new material (along the lines of Marvel’s recent “Giant-Size” titles). After learning it would be a single oversize Ed Brubaker story, I assumed it would be something quietly reflective of Cap’s career (like Brubaker’s Cap House of M story). What I hadn’t expected was a cracking good WW2-era Captain America adventure, guest starring Nick Fury and his Howling Commandoes (‘bout time!), and dovetailing nicely into Brubaker’s current run on Cap.

It’s 1944, and Cap, Bucky, and the Howlers are behind enemy lines, making contact with the Resistance. Their mission will take them across Nazi-infested fields, into an appropriately creepy mad-scientist’s castle, toward a showdown with Cap’s greatest foe and one of his fiendish creations, with stops along the way for intrigue, humor, romance, and action aplenty.

That Brubaker just gets Cap, and clearly loves Bucky, has been clear for the past year or so in the regular Captain America title, and they both get great character moments here (Bucky’s are particularly bittersweet). What was less predictable was how good the book would look without Brubaker’s regular art partners Steve Epting, Michael Lark, and Mike Perkins (though Perkins contributes the two-page coda). But this wartime tale has a different feel than Cap’s modern adventures, and the look of the book is appropriately classic, with two terrific artists each handling half of the story.

Those, like me, who miss Human Target, will be delighted to see Javier Pulido’s work here: the vibe is very much like a 60’s vintage war comic. The other half is illustrated by Marcos Martin, best known for his work in the Bat-universe. Here, he complements Pulido perfectly (you may have to look twice to spot the transition), and gets to cut loose with the big Kirby-esque action finale.

While it’s Captain America’s role as a “man out of time” that makes him such a compelling contemporary character, it’s always fun to revisit the days when his purpose in life was simply delivering a sock in the jaw to Fascism.

RATING:

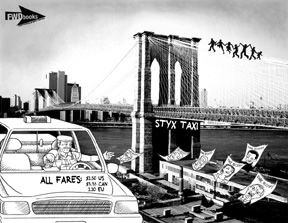

Goldman Brothers Retcon Charon in “Styx Taxi”

By Russell Paulette

Differentiation is important in this industry, particularly in your high-concept hook. Styx Taxi, an offering from indy publisher Fwd Books, certainly has that hook. Written by newcomer, Steven Goldman, the hook revolves around the idea that those who ferry the souls of the dead are taxi drivers sent by an operator who offers a once in an afterlifetime opportunity: to give the recently deceased two hours to do whatever they please before passing beyond the veil. A kind of last-chance at redemption, resolution, et cetera. In his first two one-shots, Goldman outlines the concept, and then ruminates and offers variations on a theme.

Differentiation is important in this industry, particularly in your high-concept hook. Styx Taxi, an offering from indy publisher Fwd Books, certainly has that hook. Written by newcomer, Steven Goldman, the hook revolves around the idea that those who ferry the souls of the dead are taxi drivers sent by an operator who offers a once in an afterlifetime opportunity: to give the recently deceased two hours to do whatever they please before passing beyond the veil. A kind of last-chance at redemption, resolution, et cetera. In his first two one-shots, Goldman outlines the concept, and then ruminates and offers variations on a theme.

The first of the one-shots, a 2003 tale subtitled “Pastrami for the Dead,” reads like a pilot for a television show. In it, Goldman outlines the process these taxi drivers go through with the recently deceased, telling small human-interest vignettes under the aegis of a competition between three different drivers—it seems the winning taxi driver is offered twelve hours on earth once more before they, too, are shuffled off this plane of existence. We’re mostly with Mike, the gruff newbie who goes by the nickname “Charon,” but Goldman divides his time with Mike’s competitors, Circe and Dom. Interweaving the three drivers and their various charges, Goldman manages to tell a nicely plotted tale of redemption and heartache, all while offering slices of genuine, heart-felt grief. The artwork, by Jeremy Arambulo, is well-rendered, and the storytelling decent, but unfortunately lacks a polish that would make it exceptional.

By contrast, the second one-shot, 2004’s “A Little Twilight Music,” is a photo-negative of the first. Where the earlier offering is a series of vignettes told within a larger narrative structure, Goldman chooses to make this one-shot an anthology of three tales loosely collected around a theme—you guessed it, music. The first story, “Sing Along,” scripted by Goldman with art by Dan Goldman, is a fever dream of rides given by Mike, all interconnected by lyrics from an unseen singer. The narrative is dicey and difficult to follow, and the art by the other Goldman holds an interesting stylistic conceit of looking heavily photo-referenced while retaining an illustrative quality. Ultimately, it doesn’t hold together much, except as an exercise in tone and artistic style. The third story, “Encore for my Babies,” also by Goldman and artist Rami Efal, has a much stronger narrative—a street jazz musician’s death causes her to visit fellow street performers to deliver a message of hope and peace—and is notable for Efal’s artwork, which is a combination of mid-80s Bill Sienkiewicz and modern day Kent Williams. The dreamlike quality of the artwork fits the diffuse nature of the script, but the combination of the two leads to some muddled and confusing storytelling moments. The middle story, “A Coda Vita,” is scripted by Elizabeth Genco and features some loose, naturalistic artwork from Leland Purvis, of Vox fame. This story is the strongest of the two, as it keeps its point of view narratively secure with the Mike character, and follows his innocent obsession with a classical violin busker who dies in front of him. Making a decision that breaks the rules, Mike takes this girl on her trip, and is shortly reprimanded.

By contrast, the second one-shot, 2004’s “A Little Twilight Music,” is a photo-negative of the first. Where the earlier offering is a series of vignettes told within a larger narrative structure, Goldman chooses to make this one-shot an anthology of three tales loosely collected around a theme—you guessed it, music. The first story, “Sing Along,” scripted by Goldman with art by Dan Goldman, is a fever dream of rides given by Mike, all interconnected by lyrics from an unseen singer. The narrative is dicey and difficult to follow, and the art by the other Goldman holds an interesting stylistic conceit of looking heavily photo-referenced while retaining an illustrative quality. Ultimately, it doesn’t hold together much, except as an exercise in tone and artistic style. The third story, “Encore for my Babies,” also by Goldman and artist Rami Efal, has a much stronger narrative—a street jazz musician’s death causes her to visit fellow street performers to deliver a message of hope and peace—and is notable for Efal’s artwork, which is a combination of mid-80s Bill Sienkiewicz and modern day Kent Williams. The dreamlike quality of the artwork fits the diffuse nature of the script, but the combination of the two leads to some muddled and confusing storytelling moments. The middle story, “A Coda Vita,” is scripted by Elizabeth Genco and features some loose, naturalistic artwork from Leland Purvis, of Vox fame. This story is the strongest of the two, as it keeps its point of view narratively secure with the Mike character, and follows his innocent obsession with a classical violin busker who dies in front of him. Making a decision that breaks the rules, Mike takes this girl on her trip, and is shortly reprimanded.

Overall, the talent on display in these one-shots is impressive. The narrative strengths of the first issue are weakened by underwhelming art, and a schizophrenic tone that could be helped with some more time and space devoted to the taxi drivers. Goldman does a able job giving the audience a sketch of each recently deceased, but the sketches still feel loose, and the danger with the hook comes with familiarity with the routine. Once we get it, the repetition starts to get old. As if anticipating this, the second one-shot features the experimental impulses of Goldman, which don’t work quite as well—particularly coupled with some more impressive, albiet experimental, artwork than the first go-round. The strongest piece in the follow-up is the one that followed Goldman’s lead from the first one-shot, so some sort of middle ground would be a more successful approach. That said, both one-shots display a talented group of creators, all of whom are passionate about the concept and message of the book, and, as such, deserve your attention.

RATING:

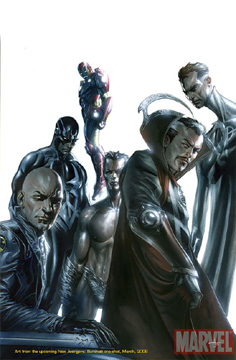

Ready or not, here comes the Civil War– New Avengers Illuminati Special Sets the Stage

By Jeb D.

Giant company crossover events are a fact of life in the superhero biz: sales figures routinely demonstrate that monthly books shed readers on a fairly consistent basis, and that regular shakeups of the status quo are needed to keep readers buying. These events are sometimes fun, occasionally interesting, usually forgettable. Marvel’s latest entry is the upcoming Civil War series from Mark Millar and Steve McNiven, and this one-shot lays the foundation for it.

Giant company crossover events are a fact of life in the superhero biz: sales figures routinely demonstrate that monthly books shed readers on a fairly consistent basis, and that regular shakeups of the status quo are needed to keep readers buying. These events are sometimes fun, occasionally interesting, usually forgettable. Marvel’s latest entry is the upcoming Civil War series from Mark Millar and Steve McNiven, and this one-shot lays the foundation for it.

In the aftermath of the Kree-Skrull War (now set at some unspecified time in the Marvel past), which saw Earth caught in the middle of a deadly interplanetary conflict, Iron Man (Tony Stark) collects an assembly of some of Marvel’s most powerful heroes: Reed Richards, Dr. Strange, Professor Xavier, Black Bolt, Prince Namor the Sub-Mariner, and Prince T’Challa, the Black Panther. His idea: to protect Earth against future threats by joining forces: The Avengers, Fantastic Four, the X-Men—all Earth’s super-powered protectors, operating under the direction of this group. The book’s title suggests a cabal behind the scenes, manipulating (and retconning) the fate of the Marvel Universe, only it doesn’t quite work out as Stark hoped. Resistance from Namor, and a scathing dressing-down from T’Challa, leaves the group less a force for change than the kind of well-meaning “Dilbert”-style committee that often does more harm than good; turns out the “Illuminati” tag is an ironic one.

The balance of the story tracks some of the group’s later interventions (one of which results in the current “Planet Hulk” storyline), some disagreements, the near-collapse of the entire idea (culminating in an absolutely vicious Namor-Iron Man showdown), and finally the first step toward the Civil War, when Stark reveals the new Superhero Registration Act, and asks his team to get behind it. Their reaction sets the stage for the crossover series due to begin early next month.

Though Millar is writing the actual Civil War series, Brian Bendis was a good choice for this introductory volume: not only will his New Avengers feature prominently in the series, but his dialog lays out the various pros and cons with some real snap, and he actually performs the unusual feat of making some of Marvel’s usually pompous characters talk like actual contemporary human beings. In particular, he’s got Namor’s arrogance down perfectly.

It’s also interesting to see such a different look from the Bendis/Alex Maleev team just months after their departure from Daredevil. There’s less of the photo-reference and grittiness that defined Matt Murdock’s world. In fact, the lighter tone reminds me of nothing so much as a classic Don Heck Avengers book. And the Namor-Iron Man throwdown is probably the best action sequence I’ve seen from Maleev since Superman-Predator.

The book concludes with a seven-page preview of Civil War that demonstrates two things: first, that Millar’s got an interesting basic premise to work with, and second, that McNiven’s ready to take his place as one of the major talents in the spandex world. Even those not inclined to big crossovers are going to have to sample this for the artwork alone.

Illuminati’s not an essential read: it’s clear from the preview that even those planning to get onboard Civil War won’t need this to explain where that story comes from. But as an examination of the questions of personal responsibility that underlie it, it’s a worthwhile one.

RATING:

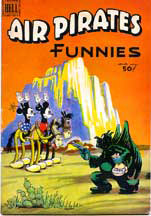

Sometimes A Cigar Is Just A Cigar: Air Pirates Funnies

By Elgin Carver

It seems safe to presume that if you read these reviews, you must enjoy comics. It does not follow that all readers have been around long enough to know about some important and/or interesting works lost in the haze of the past, and that reviews of some of these older books may be of benefit and interest. In that spirit this review will be about two of the more interesting Underground comics from more than 30 years ago, both in content and in accompanying history.

It seems safe to presume that if you read these reviews, you must enjoy comics. It does not follow that all readers have been around long enough to know about some important and/or interesting works lost in the haze of the past, and that reviews of some of these older books may be of benefit and interest. In that spirit this review will be about two of the more interesting Underground comics from more than 30 years ago, both in content and in accompanying history.

In the 1960s the fabric of American culture began to unravel. The relevant offshoot of that phenomenon was the Underground comic movement. Robert Crumb, among a few others, began to draw comics, reproduce them in as cheap a manner as possible, and sell them on the streets of places like San Francisco. Making enough money to scrape by on, they increased the quality of printing (slightly) and a distribution process, of sorts, was developed. The content of these comics differed radically from that of "normal" comics. Extreme violence, glorification of drug use, and the most graphic sex imaginable were the hallmarks of this type of book, and so their sales points were unusual – usually only head shops ( stores dedicated to the counterculture) and porno shops. Almost always printed in runs of less than 20,000 copies, and often half that, and despite the fact that almost all were printed in black and white, the cover cost was many times that of the drug store comics.

Dan O’Neill, Ted Richards, Gary Hallgren, and Bobby London joined together and published the first issue of Air Pirates in 1971. Obviously intended as a parody of both Dell Comics and older established comic characters, this issue was comprised of one page stories and short stories by each of the artists. Bobby London was clearly inspired by Krazy Kat and his Dirty Duck pages are as artistically mature a beginning for an artist as can be imagined. Witty and sparkling, he was able to expand the character in the pages of National Lampoon in later years, and even drew the Popeye comic strip at one point. Dan O’Neill’s mouse is a dead on Micky Mouse, only obsessed with sex and drugs. These stories are not for children. Some would even say they are not for adults. The Walt Disney Corporation for one, as it brought suit against Air Pirates Funnies, but only after O’Neill had a friend place copies on the conference table where Disney Corporation heads were meeting.

Much of the printing of the second issue was seized by the authorities as part of this legal action. It reflected the contents of the first, but with more work by Gary Hallgren with The Tortise and The Hare (later to have its own title) a retelling of that classic story done in an excellent, if twisted, Dell comic style, and Zeke Wolf story by Ted Richards that is clearly inspired by Disney’s Three Little Pigs.

The story of the law suit and its aftermath is long and fascinating, too much for this forum and already well documented in The Pirates and the Mouse: Disney’s War Against the Counterculture by Bob Levin (Fantagraphics Books) which is highly recommended.

Underground comics brought about a change in thinking about what comics generally could be and led to the work we enjoy today in mainstream titles. Among the best and most famous of that whole movement were The Air Pirates. The two issues should be in every serious fan’s collection. They can still be found at on-line auctions, but care should be taken in bidding as an inflated sense of value sometimes take over.

RATING:

Rucka and Samnee Detox and Debrief in “Queen and Country”

By Russell Paulette

Sometimes, a bad memory can be a plus. Having been a fan of Greg Rucka’s spy opus Queen and Country since its inception, I’ve marveled at the book’s complex interweaving of office politics and international conspiracy, and have followed the travails of its female lead, Tara Chace, as she deals with the psychological impact of what it means to kill for one’s country. This includes following the plot threads out of the realm of comics and into Rucka’s 2004 novel, A Gentleman’s Game, and then back into the ongoing series with this past week’s issue. The latest issue, # 29, marks a new storyline which picks up threads from prior issues and the aforementioned novel, then funnels the characters and events into Rucka’s 2005 novel, Private Wars, before returning to a new # 1 this coming fall. If all of that sounds confusing, don’t panic—the beauty of this issue is that it’s a perfect jumping on point, not only offering all the pertinent information you need to follow Tara Chace’s life, but also featuring the crisp linework of up-and-coming artist, Chris Samnee.

Sometimes, a bad memory can be a plus. Having been a fan of Greg Rucka’s spy opus Queen and Country since its inception, I’ve marveled at the book’s complex interweaving of office politics and international conspiracy, and have followed the travails of its female lead, Tara Chace, as she deals with the psychological impact of what it means to kill for one’s country. This includes following the plot threads out of the realm of comics and into Rucka’s 2004 novel, A Gentleman’s Game, and then back into the ongoing series with this past week’s issue. The latest issue, # 29, marks a new storyline which picks up threads from prior issues and the aforementioned novel, then funnels the characters and events into Rucka’s 2005 novel, Private Wars, before returning to a new # 1 this coming fall. If all of that sounds confusing, don’t panic—the beauty of this issue is that it’s a perfect jumping on point, not only offering all the pertinent information you need to follow Tara Chace’s life, but also featuring the crisp linework of up-and-coming artist, Chris Samnee.

Rucka’s script deftly brings new readers into the fold, while also catching up longtime fans on the events of the novel. Essentially, Tara’s last mission ended tragically, and due to her disobeying direct orders which led to that tragic end, the higher ups want her benched. Particularly because she’s showing symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, while actively in denial about it. Paul Crocker, her irascible, hard-ass boss with-a-heart-of-gold is insisting on getting her back in the field—partly due to pressure he’s getting to arrange his office to please his superiors, while pissing him off; but also because, as he reveals, it’s for Tara’s own good. By putting her back in the field, it validates her and Crocker also knows it’s will probably kickstart her out of her depression. On the other hand, it could cause irreparable damage–but not as badly as benching her. So the story follows out Tara’s coping, or lack thereof, and Crocker’s politicking to get her back into the field for both their own good. It’s an interesting dichotomy Rucka presents, and one that offers no easy answers, while giving the audience a lot to chew on.

Samnee’s linework is sharp, clear and distinct. His storytelling solid, with no distracting stylistic ticks or flourishes to get in the way. Instead, employing much of the same keeping-it-simple, stupid methodology from last year’s Capote in Kansas, Samnee depicts Chace’s world in a realistic, straightforward way. The characters are distinctive, individually expressive and capably rendered. If anything, his artwork is so plain it almost lacks a signature that would differentiate it from the work of, say, half-a-dozen other Oni artists. Instead, Samnee relies on his ability to capture facial gestures and subtle acting to stand apart from the crowd.

Overall, it’s a good introduction to the series, and a great re-introduction for longtime readers. This is one of the best books on the market, particularly because it remains driven to a singular goal: exploring all the psychological, moral, and physical ramifications that come with international espionage. From the divergent points of view of the field operative, and of the administrator, Rucka carefully constructs his world and builds each character as distinct, singular and memorable, and does so in a way that still gives us the excitement and drama one would expect from the premise. There’s no excuse not to give the series a shot with this issue.

RATING: