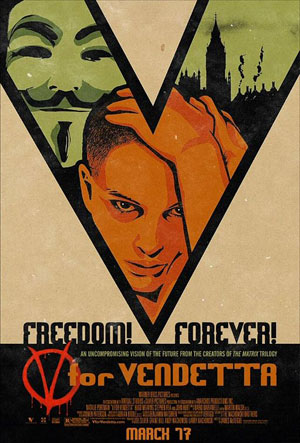

It’s no surprise that Alan Moore wasn’t available for the V For Vendetta press day in New York City – even if he approved of the film, or kept his name on the credits, he doesn’t much leave his local area these days. But David Lloyd, the comic’s co-creator and artist, was on hand to support what turned out to be one of the strongest comic book to movie adaptations of all time.

It’s no surprise that Alan Moore wasn’t available for the V For Vendetta press day in New York City – even if he approved of the film, or kept his name on the credits, he doesn’t much leave his local area these days. But David Lloyd, the comic’s co-creator and artist, was on hand to support what turned out to be one of the strongest comic book to movie adaptations of all time.

He wasn’t alone. I’m not a huge fan of the “Let’s throw all the talent in a room at once” approach to movie junketing, and that was what we got that day. Thankfully, the folks from V were on point, and for once my room wasn’t filled with journalists asking lame-ass Teen Vogue questions. And considering that Natalie Portman, a magnet to tabloid types, was there, that’s saying a lot.

Joining Natalie and David were producer Joel Silver and director James McTeigue. V marks McTeigue’s directorial debut, although he’s been assistant director on many films, including The Matrix films and the Star Wars prequels. If you don’t know who Joel Silver is, you may be reading the wrong website.

Q: David, did you have any idea, back when you were doing this in the ’80s that this project would have this extended life?

Lloyd: No, we didn’t know what our success was going to be. It just caught the public’s imagination, initially with comic fans. We actually constructed it for people who don’t normally read comics so we were getting a lot of people who didn’t read comics reading it. And then when DC bought it ’88, and it was collected as a graphic novel—it just kept on going. It became one of those two textbook graphic novels that everyone knows about— Watchmen is the other one. I’m glad that it’s been made into a film, and a very good one that keeps the whole spirit and integrity of the original. I’m happy to be here to talk about it.

Q: Did you have any collaboration with the film?

Lloyd: No. I was sent the script before the production began, and made a few comments about it , but I was lucky that I was sent the script for the project and was asked for my opinion of it. The first one that was sent to me was not really that good but anyway… [laughs]. This one was great, and it turned into a great film.

Q: Natalie, when you got this part, did you read the comics as well as the script?

Portman: Yeah, when I was offered the part, I was given the graphic novel, and that was a great resource to have because it’s practically a storyboard for the movie. It’s kind of amazing.

Q: Were there parts that you wish could have made it into the movie?

Portman: I think that some of the sub-plots were excised so that it could have a smoother narrative, and obviously the parts that weren’t in the script we luckily had in the graphic novel to give us a more of an imagination of the details of that world that you just can’t put into a film because you don’t want the audience to be sitting there going through pain for having to sit there so long.

Q: This film raises questions about what’s a freedom fighter versus what’s a terrorist, as well as when violence against the state both allowable and necessary. Natalie, you did a lot of research before undertaking the role, specifically about Menachim Begin. What did did you learn from that research?

Portman: That book in particular was very helpful with details of what one’s thought process may be like in an imprisonment situation that would eventually lead you to a place where violence was an acceptable means to convey your political beliefs.

There was also a book I read, which we all ended up reading, called Cloud Atlas, that was pretty formative to my ideas about violence because it has this story of the Moriori tribe in it. They were this non- violent New Zealand tribe that thought that if you committed violent acts your soul will be tainted, and you would become an outcast in their society. So the Europeans came and now they no longer exist [laughs]. The problem with non-violence is if you have violent neighbors, you cease to exist which is sort of like violence to yourself.

That helped me to understand violence, because that self-defensive violence is one that I can understand as a human being, but that can be extended to such a large thing. If you think that you would defend your family from a threat, or you’re a president, and your country’s your family, what if the threat is perceived rather than real? All of these things posed questions that you could talk about for a lifetime, and never really come to solid conclusions.

Q: Joel, are films like The Matrix trilogy a carrot that’s held out in front of you? Is it a question of "Can we do this again? Can we make lightning strike twice?"

Silver: I think with all movies you want to make something special. I’m in the commercial movie business, and I try to make movies that are effective and successful. Usually they’re very costly, and this one was a fraction of the cost of The Matrix movies. You have to do whatever you can to bring the audience to the theater, so the question becomes what will bring them in? I made a movie this year that I loved, and that nobody went to see called Kiss, Kiss, Bang, Bang, and I enjoyed it. It was a little picture but I tried it, and my reward for making good movies is seeing people come and see them. That’s the idea, and I hope that this movie will do that.

Q: Did you have any trepidation about how far to go in terms of effects, because this movie is really minimal on special effects.

Silver: We follow the graphic novel that David and Alan created: the intention was to tell this story. It’s been in the works a long time— we acquired this in the late ’80s. Some things happen very quickly—a script gets made—and some things take a long time to get to the screen. It has action elements that allow us have an action movie masquerading as something else. It’s a smarter movie than most; I’ve made a lot of stupid action movies before, and I’m proud of those films, but along the way we discovered people want to see something that has a little more there, that has a little more going on. This movie could work if you don’t want to focus in on any of the material, and just wanted to enjoy the explosions and the knife fights, but there’s a lot more there. That’s what we tried to do, and I think we succeeded.

Q: Natalie, did working opposite Hugo Weaving while he was wearing the mask the entire time pose any new challenges for you as an actor?

Portman: Hugo is such an amazing actor that just by his physical and vocal expressions you could tell exactly who he was; I think as an audience you can feel that. There’s also sort of engagement that takes place because you’re always wondering what’s going on behind it. You’re asking yourself, "Is he crying now? Is he smiling?" You’re trying to get into his mind in a way to the point where you almost become V.

There’s this incredible engagement that’s even more exciting than normally. I think that with the action stuff you were talking about earlier it earns its action scenes. It has a compelling story so you actually care about what’s going on in the action scenes. It’s not

gratuitous, and the action scenes are a great reward to that story because they’re pretty stylized, and are stuff that you’ve never seen before. It’s like a sweet taste.

Q: Were you guys having a healthy debate on politics throughout the making of the film?

McTeigue: Yes and no. I think that once you have the script in your hand, you realize what the politics of the piece are. We still passed around books that we felt were relevant, but the script was there. It wasn’t a day-to-day argument, it was more a peaceful thing.

Portman: I think you also can’t be too "what is this about" all the time. You have to focus on the story and the characters and not a larger meaning because once you make it specific you can draw internal conclusions from that.

Q: James, going back to Hugo – he wasn’t the first actor to be cast as V. What were some of the challenges of bringing him into the production, and bringing him up to speed? I guess you guys had already begun shooting, so what was it like to have somebody else in that mask?

McTeigue: With Hugo, in the conversation I had with him on the phone before he came over, I told him, "If you’re going to come over, there’s one thing I ask: make peace with the mask." He said, "That’s not going to be a problem." So he came over, and he slotted straight in, and he is an amazing actor like Natalie was saying before, and he really got it. He really knew what the mask could do, and I think that followed in his thespian tradition. He knew how to work with a mask. Even though when he was playing across Natalie he was looking at a stomach because the range of vision was so…

Portman: Yeah, my stomach. [laughs]

McTeigue: He had such a great sense about it, and Natalie and me and Hugo, we just trusted each other to say if things weren’t working, but he got it really quickly.

Q: What was that mask made of?

McTeigue: It’s made from fiberglass but it’s from a clay mold. We took great care making sure that the mask had a human quality to it. It was so beautifully drawn in the graphic novel, but David cheats a little bit: he makes him smile in some panels, and frowning in others. It wasn’t so much heavy, it was hot, and confining. Like I was saying before, where he was looking was rather limited.

Q: How long could he wear it at a time?

McTeigue: He’s a trooper. He’s also a sweater [laughs]. Sometimes he’d keep it on for multiple takes depending on where we were.

Q: So you didn’t try it on at all, Natalie?

Portman: With Hugo’s sweat in there (laughs)? I think the make-up artist’s main job was to wipe the beads of sweat off the mask’s beard.

Lloyd: How’d you fix it on his head? I have no idea how you did that.

McTeigue: It had two elastic ties that goes on the top of his head as well as underneath the wig.

Q: Comic book fans are known for being puritanical. Are you afraid they’re going to come after you, James, for any changes you’ve made or you, David, for letting them be changed?

McTeigue: I think that’s a question for David [laughs].

Lloyd: There’s a bit of history behind it, because Alan sort of disapproves of things, I was in a position to go to the comics community to say, "Look, this really good. Trust me." A lot of people had heard on the internet Alan’s problems with things—he didn’t like

the script et cetera, et cetera—and I was saying to everybody, "Look: it’s not a perfect book-to-screen adaptation but it’s a great adaptation. The spirit, the integrity, the message is all there from the original. It’s very imaginatively changed. It’s got great symbolism attached to it."

And one of the things I mentioned to people was the thing that struck me about it was that it’s like a political cartoon in a newspaper. The adaptation uses much broader sweeps than we did. In the graphic novel, we had lots of space, but in the film they had to use much broader sweeps. The symbolism is used much more effectively, and it’s great. All the people I know who’ve read the original graphic novel, and were big admirers of it that I spoke that told me that they were really worried about it, and uncertain, a lot of those that have seen the film through various screenings that have been arranged, they all said that they’re really happy with it. I think that’ll be the long-term effect once everyone gets a chance to see it: all the hardened fans will see that it still retains the major portion of the book. I think it’s great, and I’m happy to support it.

Q: Natalie, did you have any desire to talk to Alan or were you just happy to go with what you had before you on the page?

Portman: I’m a huge fan of the graphic novel, and I think all of us—while I can only speak for myself, but I have the feeling that all of us—made this with the greatest respect for the graphic novel. If he didn’t want to be involved in the project, you gotta respect that; I’m not going to force him to do that. The greatest gift that he and David gave us is the graphic novel. There’s so much in there to draw from.

Q: Joel, what kind of things were you looking for in a heroine? Was this a drawn-out audition where Natalie had to prove herself?

Silver: Well not…

Portman: Yes it was, don’t lie, Joel [laughs]!

Silver: She really was our first choice. The Wachowski Brothers are big fans of a director by the name of Tom Tykwer who they met along the way, and they like very much. Natalie had done a short autobiographical piece with him…

Portman: Not autobiographical about me, autobiographical about him [laughs].

Silver: They saw it, and they were blown away by it.

They wanted to know that she was committed to doing this, not just shave her head but also understand the character and know what it’s about, and go through the arduous task of creating this girl because she’s on-screen for practically all of the movie. And she went to San Francisco just to see Larry or James, and they loved her. Why wouldn’t they? We know how great she is and we love her dearly.

Portman: Thank you.

Silver: But she got it. She understood what the movie is about, and what we were trying to do. When you make a movie like this, she becomes your partner, and she’s a fantastic partner.

Q: Natalie, can you talk about meeting those guys? What did they ask of you in those interviews?

Portman: I read the scene at the kitchen sink, and the scene where I realize that I have to stay in the Shadow Gallery. They made me fly to San Francisco from Israel, where I was going to school, which was very friendly of them [laughs], so I went in like "grrr," but they were so great. I know James from before; we worked together on Episode II so it was great seeing him again. Larry was an amazing person to get to know: he’s so smart, and interesting, and passionate about filmmaking. So we had a great talk about the material and I tried to make them think I was sweet and cute [laughs].

Q: What were the classes in Israel?

Portman: I went for a semester of grad school last year and I brushed up on my Hebrew, and some Arabic. I took classes on Islam, and the history of Israel, and the anthropology of violence which was very informative for this film.

Q: Joel, there’s a perception about the last two Matrix films about how they underperformed. Then there’s the negative press that the Wachowskis have received recently in the last year or so. Does that affect how they’re dealing with things in Hollywood and how they’re dealing with things with you? Does it affect their future projects?

Silver: You have to realize that The Matrix movies returned $3 billion in revenue to Warner Brothers; I don’t know how you can figure out a way that that’s not a successful venture. There’s no way. If you look at it, it’s the most successful adult-based—because it’s R-rated—series of its time. I don’t think anyone can achieve what it achieved. We deal with the situation that people have their own opinion, which I think they do, and a lot of the times their work is complex, and they don’t really take time to explain what they’re doing. They just present it as it is, and sometimes that makes people uncomfortable that they don’t understand where they’re going.

Look, they’re brilliant filmmakers. They are brilliant filmmakers. They didn’t direct this movie, James directed this movie. They were very supportive—I mean, they wrote the script based on David and Alan’s work—and were available for James to help him through the process, and they produced the movie with me. We’ve been together for ten, twelve years or so; we’ve been doing this for a long time. I love working with them. They’re very great artists, and their art tends to be commercial. I hope that people will be drawn to this movie because I think it’s a great film, and I think people enjoy it, and it’s got a lot to say.

They’re the kind of filmmakers that can do whatever they want. They tend to be provocative in the movies they choose to make — Bound was provocative; it was a little movie but it was extremely provocative. Assassins would’ve been a great film too that they wrote if it hadn’t been blown off course by the people that were making the movie, and I think that they have lots of interests and a lot of passions. They’re two very different guys, but they work together very well. I’m encouraging them to go back to work again…

Q: That was my next question – when are they going to direct again?

Silver: I’m trying, I’m always trying, all of us are: Warner Brothers, myself, their agents. But they’re guys that work when they want to work. On Reloaded and Revolutions they shot for 270 days straight. I don’t care who you are: making movies for 270 days straight is an impossible feat. The other guy that did it with him was him [McTeigue]. But it was an impossible feat and they got through with it. They wanted to take time off, and this has been their time off, this movie, which they didn’t direct, so they didn’t have to be there at 5 in the morning, James did. They were always there when somebody needed them, they flew out to Berlin or the UK where we were working. I hope that they come back to work soon, and I’m encouraging them to do so.

Q: Joel, you mentioned the great Kiss, Kiss, Bang, Bang; you loved it but nobody responded. The more you do this, do you learn more? Is there some great truth that you learned or do you never know about putting stuff out there and how people will respond?

Silver: I don’t have a clue [laughs]. I try to put out what people want to see, and what I want to see, and I hope people agree with me. There’s so many things at work: climate and timing are so important to a movie, what’s going on around it, and what’s opening the same week it opens are important issues that have to be addressed. The stars have to align to make a movie work. People will say that it’s a miracle to make a movie made at all in our business. Forget about getting it made, and having it be good, and then in turn a hit. That’s impossible, but you keep at it. I just finished up a couple of pictures, like this one movie with Hillary Swank called The Reaping which will open in the summer, and another picture with Nicole Kidman called The visiting which will come out next year, and this other picture with Jodie Foster and Terrence Howard—I have all the strong, muscular, female-led movies coming up. I’m positive about the movies, and I think this one is really good, and very effective, and very strong, and I’m proud of the whole group here, and the movie we made, and I think people will respond to it.

Q: James, you’ve had such a longer career as an assistant-director working at the front lines; did that completely prepare you for your first experience as a full-time director, or were there things that surprised you?

McTeigue: Like Joel said, you can’t shoot a 270 day shoot and not learn something. It really sort of freed up the creative part of it because I innately know the machinations of how filmmaking works. A lot about making a film is trusting people so I really could feel that the people behind me could do the things I was trusting them to do. That was a great thing to have behind me. I can’t imagine what it must be like if you’re a screenwriter, and all of a sudden they say, "Ok, here’s your first film," and you’re on-set with 150 people, and up until then you’ve been writing in a garage alone somewhere. I’ve done a lot of larger films, and a lot of smaller, independent films and they all sort of help you in the mix to do it yourself.

Q: Natalie, you’ve now worked in two films where you’re on the rebel side: what insights do you have as to what rebels are all about?

Portman: What rebels are all bout? I don’t know, I guess the main thing I though about was what would it take for me to become violent, and I thought about it, and I thought, "to defend my family," and you realize how that can be extended on such a large scale if you think your religion’s your family, or that your whole country’s your family, and if the threat you’re perceiving is just perceived or if it’s real, and how that can turn into wars, which is something that I think all of us have had the feeling of "Why can’t they just talk it out" [laughs]? It’s naïve certainly, but it’s in imagining how violence starts that the whole thing starts.

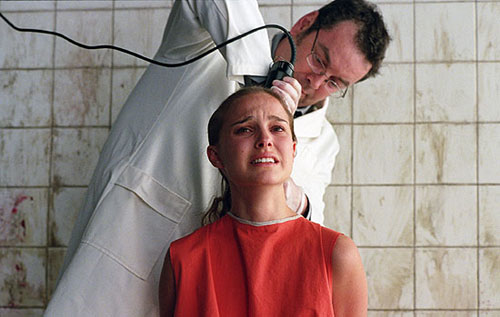

Q: Did you know going in that you’d have to get your head shaved?

Portman: Mm-hmm.

Q: Did you have any trepidation about that?

Portman: No, it was always something I’ve wanted to do. Making a dramatic change that isn’t reversible is always a worthy experience, and that sort of gave me the courage to do it. And obviously for the character, it’s a very traumatic experience because of how it’s forced upon her, and in such a violent way, it’s committed upon her.

Q: It must be tough doing it on camera, where you can’t do another take.

Portman: That’s the biggest stress of it. For the rest of the movie, if we make a mistake, we can always do it over, but not this scene. So they had several cameras on it, they had practiced with several razors, and the crew even volunteered to get their heads shaved, and made sure everything was working. I just tried to focus and do my best in my one

chance.

[POSSIBLE SPOILERS IN THIS FINAL QUESTION]

Q: Evey has to make a choice in the film about the use of violence. Does that say something about how violence is necessary part of growth?

Portman: I think that her decision and the audience’s judgment of it are totally separate. She obviously finds it necessary to commit that act, and I think the great thing about this movie is that it leaves that question up to the audience. Obviously we feel that the cause is just, but the means used are open to interpretation, and obviously throughout history violence has been pretty effective means of creating revolution, but it’s also obviously not been the only way, or anyone’s ideal way.