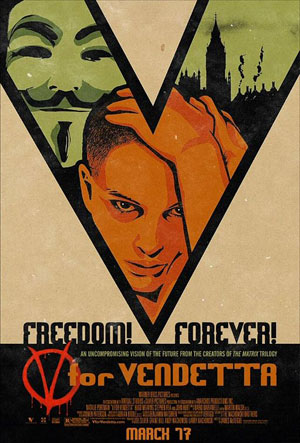

Let’s get this out of the way right up front – I think that the film version of V For Vendetta is better than the original comic. Seriously.

Let’s get this out of the way right up front – I think that the film version of V For Vendetta is better than the original comic. Seriously.

The hardcore fans will say that the film ruins the comic, removing tons of subplots and backstory, but I would say that the film streamlines the comic, bringing ideas to the front and center, and doing what great art should do – commenting on the world we live in. The original comic (and I will be damned if I call this thing a graphic novel) was mostly published in installments of a few pages each, creating a story that rambles and meanders, spending time with characters who are completely extraneous and sometimes traveling down narrative dead ends. James McTeigue’s version of V, as written by the Wachowski Bros, clears a lot of the dead wood and gets straight to the heart of the story while never betraying it for cheap and easy action scenes.

In ten years we’ll probably still be arguing on the CHUD boards about how much involvement the Wachowskis had with this film. My take is that it’s a genuine McTeigue film, heavily influenced by his work with the Bros on the Matrix films, and possibly featuring a final fight scene directed by them (I would almost bet money on it, in fact). In a lot of ways I wish the Wachowskis had directed this film – in a world where the horrible Matrix sequels don’t exist this movie would be the final proof of their genius, cementing the themes that make them auteurs, everything from secret societies and initiations to the fluidity of identity to the battle against fascism. It’s exhilarating to see how talented filmmakers can take the work of another and adapt it into something that respects the original and yet bears their personal imprint.

The film moves the comic’s timeline up (it has to – the comic is set in our recent past, which was the future when it was published), and changes some of the backstory to one that makes more sense today. Instead of a nuclear war that somehow leaves Britain unscathed, there’s a slow tightening of a fascist grip, sparked by public panic over a bioterror attack that kills hundreds of thousands. When Moore and Lloyd were creating V, nuclear war wasn’t just a fear – it was seen as an almost eventual certainty. Now a global nuclear conflict feels almost quaint, but a massive bioterror attack feels like this weekend’s headlines.

The film also smooths out some of the comic’s silliness. In the comic the fascist leader of England is in love with a computer. A radio show is broadcast daily that purports to be the voice of that computer. V drives a man mad by screwing with his doll collection. Some of this stuff doesn’t even work on the page – seeing the leader mooning over a computer monitor is endlessly ridiculous, so thank God that was removed.

What isn’t changed is the central enigmatic figure of V himself, the masked terrorist who is looking to bring down the fascist state and return power to the people. Actually, he might be even more enigmatic in the film – the Wachowskis and McTeigue dispense with some of the character’s history (without ever contradicting it – fans of the original work can know that the key moments still exist, between the frames), making him a touch more shadowy. It’s a brave thing to do – we never see his face and never learn that much about him, even though he’s one of the co-leads. But it’s right, as is the casting of Hugo Weaving, a late addition whose voice carries the character’s cold intellect and whose sheer physical presence defines his grace.

Natalie Portman is fantastic as Evey, the girl who V rescues early on and teaches about the way the world was, and about what freedom is. It’s possibly Portman’s toughest role since The Professional, as she must be broken down and remade during the course of the film’s running time – Evey’s journey from TV station intern to potential freedom fighter is the path that takes the audience along to the point that we understand that every now and again maybe you really have to fuck things up.

And that’s exciting. Too often the message is just the opposite, that violence is a tactic best relegated to our Founding Fathers. It’s the debate about when it’s acceptable to use violence that’s at the heart of the film – V spends most of the movie getting his revenge on the concentration camp guards and scientists who experimented on him decades ago, and the question of the morality of these actions hangs over the movie. They come to a head at the end, when the difference between violence in service of revenge and violence in service of revolution is made clear.

And what an end it is – there’s pyrotechnics galore, but the really thrilling moment is when the people of London rise, wearing the outfit of V, and take to the streets. The movie uses this as a perfect metaphor – they come together under the banner of an idea (in this case V), a crowd of individuals merged as one. Then at the end they triumphantly remove the masks, never giving away their identity. It’s the single best screen representation of what it is really like to be part of a giant protest or movement, the way that you are still an individual while also being part of a bigger, almost sentient organism.

Some people have complained that the Norsefire regime of the film is a straw man, that the debate over whether it is right to use violence against Norsefire is no debate at all – it’s obvious. On some level, sure, that’s true. The film needs to get to the point, though, and by setting the story in an England that is very familiar even to American audiences, the parallels to the modern world are much more obvious – some levels of nuance are lost, but it’s not catastrophic.

I don’t usually use reviews to answer other reviews, but here I feel compelled to do so. In his excellent review of this film, Collider’s Mr Beaks (pound for pound the best writer on the internet, and don’t let his slim frame fool you), feels that the movie overreaches by creating a worst case scenario world, one that probably would never come to pass. That’s reasonable, although I can’t see complaining about it – popular movies tend to work in the realm of the extreme. Where he loses me, though, is this claim: “If there’s one freedom no one’s willing to relinquish in this multimedia age, it’s the freedom of choice.” It’s that loss of freedom of choice that strikes me as the most realistic thing in the film’s future. It’s important to note that there’s a reference to a TV show having ratings at one point – there’s choice in V’s future, but it’s false choice, since everything is, in the end, controlled by the government and its censors.

How different is that from today? Sure, it’s not government censors who control our options, but we’re presented with illusory choices – two political parties that are more alike than they are different; massive radio networks that spread across the country, choking out local sounds; channel upon channel of the same basic crap on our cable; a handful of corporations that create and distribute almost every piece of media we consume. We like to think that there’s choice out there, but at the end of the day the best that you can say is that you voted for Kodos, not Kang.

What makes V a fantastic film is its complete watchability. It’s a movie without many action scenes, and it’s filled with speeches and exposition, yet there’s not a boring stretch. Is it a great film? I don’t know – we’ll see where it stands in five or ten years. But it is a great film for now – not just politically but artistically, a shining example that our entertainment doesn’t need to be geared to the short bus crowd to be successful.