I’m an unabashed fan of 19th century New York City, and part of what I love about that time period is the unabashed corruption of the “machine” system of politics used by people like the infamous Boss Tweed. The levels of fraud, intimidation and actual violence used to guarantee continued incumbency for preferred candidates makes Florida 2000 look like the zenith of democracy. But as much fun as that stuff is to read about, there’s the comfortable cushion of history that makes it all less serious. Then along comes a movie like Street Fight, which is filled with the kinds of tactics that made Tammany Hall, but the election it’s documenting was in 2002.

I’m an unabashed fan of 19th century New York City, and part of what I love about that time period is the unabashed corruption of the “machine” system of politics used by people like the infamous Boss Tweed. The levels of fraud, intimidation and actual violence used to guarantee continued incumbency for preferred candidates makes Florida 2000 look like the zenith of democracy. But as much fun as that stuff is to read about, there’s the comfortable cushion of history that makes it all less serious. Then along comes a movie like Street Fight, which is filled with the kinds of tactics that made Tammany Hall, but the election it’s documenting was in 2002.

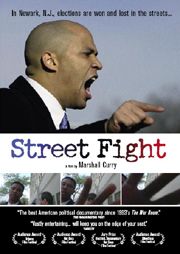

The documentary follows the Newark, New Jersey mayoral race in that year, pitting new jack Cory Booker against Sharpe James, seeking his sixth term in office. The film is unabashedly biased – Booker is a saint, while James is a corrupt, possibly insane asshole. To be fair, that bias comes about because the James campaign instantly – and violently – shuts out director Marshall Curry. To also be fair, the bias comes because it honestly seems like the James campaign is evil. The things they do, the lies they tell, during the course of the election will leave you stupefied.

Stupefictation quickly turns to outrage. It’s hard to imagine that things the Sharpe James campaign does – breaking into Booker’s office, detaining supporters as possible terrorists, illegally removing campaign signs, using the city police force to strong arm local businesses into not supporting Booker, claiming that Booker isn’t black (he’s light skinned but his parents, who were involved in the civil rights movement, would be surprised to learn he’s white) – happened in New Jersey’s biggest city just four years ago. It’s astonishing to see Sharpe James freak out on reporters on TV, blatantly ignore federal court rulings and bald faced lie every single chance he gets, and get away with it.

At first I loved Street Fight because it was showing me rough and tumble politics that happened outside of Q ratings and massive media buys, the kind of old-fashioned politics where going door to door is actually important (the Sharpe James campaign brings in a media consultant who says that in all the elections he’s worked on he’s never seen one so old-fashioned. He also marvels at how generally evil and ignorant the Sharpe James campaign is), but after a while the movie started making me depressed. I don’t know the real differences in policy between Cory Booker and Sharpe James (besides the fact that James, who presides over a very poor city is one of the best paid mayors in the country), but I do know that Booker is an idealistic young man who is crushed – as we watch – by the brutal intensity of his opponent’s dirty tricks. It’s a capsule example of what is wrong (and, by the way, really always has been wrong) with electoral politics in this country, where it isn’t the strong who survive but only the most underhanded and devious.

Director Curry does an admirable job of letting the images and the Sharpe campaign speak for themselves. The race ends up being fascinating on many levels, not just because of the rampant corruption and dishonesty – it ends up being an argument about race in the “post-civil rights” era, where a black man whose family worked to get him into Yale can be accused on not being black. What is the message being sent to the kids in Newark? It certainly isn’t “stay in school.” It’s interesting to consider these two opponents as if they were in a Hollywood film, as well – Booker is a light-skinned, Vin Diesel looking Ivy Leaguer while Sharpe James is a darker skinned man who has been part of the political life of Newark since the 1960s. The good guy/bad guy cues are spread all over the place on this one.

Sometimes politics is a bloodsport, and Curry captures that here. Street Fight isn’t going to restore your faith in our desperately broken electoral system, but Cory Booker – and the last moments of the movie – may help you harbor that little flame of hope.

Street Fight is nominated for a Best Documentary award at this year’s Oscars. It opens in New York this weekend.