A man wakes up one morning on the D train in Coney Island with no idea who he is. He’s wearing shorts and has a backpack containing a vial of liquid. In his pocket is a phone number he doesn’t recognize and when called, the woman on the other end doesn’t know him.

A man wakes up one morning on the D train in Coney Island with no idea who he is. He’s wearing shorts and has a backpack containing a vial of liquid. In his pocket is a phone number he doesn’t recognize and when called, the woman on the other end doesn’t know him.

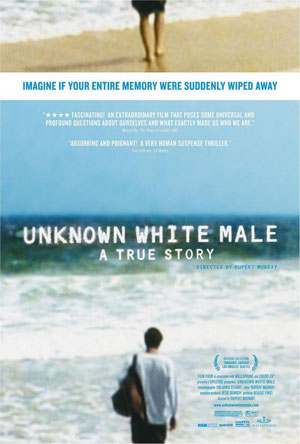

That’s the beginning of Doug Bruce’s story. Suddenly, and without explanation, he forgot everything in his life. Unknown White Male is the story of his struggle with this bizarre case of amnesia, sort of a non-fiction Memento.

In the days after his amnesia, Doug began recording himself getting used to his newly rediscovered life. A few months later, an old friend from before the amnesia, Rupert Murray (pictured above – other images are Doug), asked to make a documentary about him and his condition. It’s the kind of story that’s almost too incredible to be true (and some people have claimed that it isn’t, insisting that Unknown White Male is the new Blair Witch Project) and that makes you examine the deepest aspects of what it means to be you.

Director Rupert Murray was kind enough to spend some time on the phone with me last week talking about Doug, the film, the eventual DVD release, and the controversy over Unknown White Male‘s veracity. The film is playing in Los Angeles and New York starting this Friday – see it to decide for yourself.

Q: There are some people who are naysayers about the film, saying that it’s all too convenient and in the post-James Frey, A Million Little Pieces world, we shouldn’t be so quick to believe everything that’s on display here. Do you want to respond to that?

Murray: I don’t know. The film is completely true, is my response. It’s strange that I find myself in this situation, that the release of the film is coinciding with this phenomena. The thing about Doug’s condition, with amnesia, and particularly in his case, is that there’s no proof it actually exists. It’s an action that goes on inside his head; it’s his perspective. You can’t physically or conclusively prove that that is what he’s experiencing. The only thing I can say is that the only people who don’t believe it are the people who didn’t know Doug before his accident. Anyone who knew Doug before his accident and looked him in the eyes knew straight off that there’s no way he could fake that.

Q: Do you think it matters if Doug’s amnesia is a physical thing or a psychological thing?

Q: Do you think it matters if Doug’s amnesia is a physical thing or a psychological thing?

Murray: I don’t think it does make a difference. Quite early on the doctors drew a blank as to what caused it. He had various symptoms, he had a small bleed upon his pituitary gland, he had a slight slowing down of his left temporal lobe, he had some bumps on his head, but they couldn’t conclusively link any one of those elements to his amnesia. Quite quickly he decided, as he wasn’t getting any conclusive answers from the doctors that he would leave that behind and concentrate on his future, to embrace the world ahead of him rather than dwell on a possible cause. It was costing him lots of money as well.

Q: What’s interesting to see is how the amnesia affects him. He understands what a hospital is, he can speak idiomatic English, but he’s rediscovering food, he’s rediscovering the Rolling Stones.

Murray: Of all the case studies that I have read I have never found one quite like Doug’s condition. I’d never heard of someone forgetting what food tastes like. What it is is that he completely forgot any personal experience that he had. But a lot of previous experiences, especially the repetitive ones, were transferred to his procedural and semantic memory. That manifested itself in things like if your mother tells you how to hold your knife and fork properly, he wouldn’t remember any one particular episode of that happening, but he would know how to hold his knife and fork properly. His procedural memory was intact. That’s why he sounded very similar to the previous person. He had the idiosyncratic language of someone who had his upbringing and his background.

Q: How is Doug today?

Murray: He’s very well, actually. He hasn’t had any memory return, although he occasionally thinks that he hears something or sees something or smells something familiar, but he can’t tell whether it’s something he’s experienced after his accident. He’s doing extremely well, he’s in a great relationship and he’s very happy with his life.

Q: In the film Doug seems to come to the conclusion that he doesn’t want to remember anything because the new person that he is is someone that he likes. Does he still feel that way?

Murray: He’s never said that he desperately wants all of his memory back, but I think that there are lots of elements of his previous life that he’d like to remember, like the memory of his mother and having grown up in Africa as a child. But in a strange way, he’s learned so much about the previous person that – you know, a lot of my memories of what I was like as a child and what I did as a child, do I actually remember them or did I form memories of things that people told me I did? I have this incredible memory of me watching the landing on the Moon with my grandmother. I can see myself sitting there watching it with her. Freud says that if you see the memory from not your own perspective, it’s much more likely to not be true because you didn’t experience it like that. My family told me for many years that I watched the landing on the Moon with my grandmum, and I formed this image in my mind, which is not true. I think that Doug has learned about lots of things from his past. He’s become a person that’s not a million miles away from the previous person, so in a sense he’s got his memory back in that he knows a general timeline of his past. I don’t feel that there’s any kind of void there.

Q: Could you have made this movie if Doug hadn’t been documenting his own condition early on?

Murray: I could have made it but it wouldn’t have had anything like the impact. I joined the film quite late – it was eight months into his amnesia before I summoned up the courage to contact him. You really need to be of that time. Also, I didn’t realize that he had these home movies when I started to make it. The footage of him going to meet his father and his sister for the first time. It was incredible.

for the first time. It was incredible.

Q: When you’re making a film like this, how do you know when to stop making the film? Doug doesn’t get his memory back.

Murray: When you run out of money!

We felt that we had reached an end to the story. It was nearly two years after it happened, he had gotten his life together, was in love with Norrell and was moving on. The fact that he was beginning to get interested in his past, that felt like an ending to us.

Q: How much say did Doug have in what you do or don’t show?

Murray: The basic thing is that he was just a fantastic contributor. There was no part of his life that was off limits. I wanted to make it very much in collaboration with him because it’s such a personal thing. It’s about a very large percentage of his life – he’s only two and a half years old. I wanted to get as close to Doug’s experience as possible, to reflect it as truthfully as I could. I knew that if I did that people would be much more like to experience, vicariously, some of the revelations that his amnesia brought about, which is what happened to me. I think he could have made editorial decisions when he saw the rough cut. If he had objected to any material, I would have taken it out if it would have been detrimental to any relationships he had at that time with any people. But luckily I didn’t need to do that.

Q: Someone said that after watching the film they felt that amnesia is the ultimate self help tool. Do you believe that – has amnesia made Doug a better person?

Murray: I think it’s kind of helped. In a way what’s probably made him a better person is the fact that this experience has been character building. He battled his way through this experience and he’s come out on top, and he’s controlled it, he’s worked with it, and he’s made the best of it. That’s a credit to who he is as a person. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

Q: The whole thing speaks to the base of the nature versus nurture debate – you take someone away from their nurture completely and see what kind of person they become.

Murray: It won’t give you any answers, but I don’t think there are any answers to that debate because there are so many variables. But it’s fascinating to think about it in light of Doug’s situation.

Q: I think one of the reason some people have asked if the film was a hoax or not is because the story is just so compelling. Have people tried to option Doug’s story for a narrative film?

Murray: There’s been quite a lot of interest. We’re in talks with people, but we haven’t made any decisions yet.

Q: Is he considering writing a book or anything?

Murray: He isn’t at the moment. The thing with people believing it’s a hoax is that it’s a compliment where they think it’s too good to be true.

Q: What’s next for you? This film must be changing your options.

Murray: It is. I’m not entirely sure – I’ve got loads of ideas, but I’ve been really concentrating on releasing this film because it’s been such a departure for me and I wanted to give it all my attention. When I get back to England I’m going to look at lots of different ideas.

Q: A lot of my readers are probably never going to get to see this in the theater, because it’s a smaller film and a documentary, and won’t play on that many screens. What are the plans for the DVD release?

Murray: I’m afraid I don’t have the date, but I’m thinking about the DVD at the moment. The audience reactions to the film have been – it’s been the most memorable experience of my life, with people coming up to me afterwards saying how much it moved them, and how much it inspired them, and how much it made them question things about their own life. The Q& A sessions are very long always, and everyone stays and wants to know everything, so what I’m going to do is that I’m going to replicate those Q&A sessions and the issues that arise and address them on the DVD. There are lots of medical, philosophical and spiritual aspects that I want to include as well.

Q: It’s the philosophical stuff that I think ends up being the most fascinating. It allows us to look at a lot of existential questions in a different way – just what the meaning of who we are, our identity, is.

Q: It’s the philosophical stuff that I think ends up being the most fascinating. It allows us to look at a lot of existential questions in a different way – just what the meaning of who we are, our identity, is.

Murray: That was one of the interesting aspects for me. It wasn’t something that I initially thought of. The way that the film developed, the narrative of the film, is that as I began questioning things deeper I didn’t know how to phrase my questions, or what kind of questions I should be asking. I turned to leading experts, who were brilliant. There are no answers – the film doesn’t provide any answers, but it’s a fascinating place to ask these questions.

Q: I think it’s the very best date documentary I have ever seen. You take a date to this and there’s endless conversation that comes out of it.

Murray: Brilliant! I never heard of it called that before. That’s fantastic.