Back again with another roundtable format of The Chewer Column. I’m already knee-deep in the next installment which will deal a bit more substantially with the whole Comic Book Film craze of this passing decade, and then possibly have one that focuses on the cinema of Michael Mann. So stay tuned for those.

Back again with another roundtable format of The Chewer Column. I’m already knee-deep in the next installment which will deal a bit more substantially with the whole Comic Book Film craze of this passing decade, and then possibly have one that focuses on the cinema of Michael Mann. So stay tuned for those.

There’s a wealth of stuff to go through here and since I don’t have much else to say, I’m just going to shut up and let the article speak for itself. But please note, since this is an in-depth examination of a set of films, SPOILERS WILL BE ALL OVER THIS THING. So tread lightly.

Enjoy, folks!

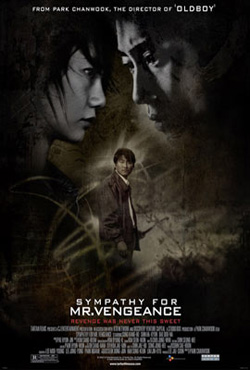

Vengeance: A Walk in the Chan-wook Park

By Nathan Wishart, Giles Edwards, Steve Atencio, Charlie Brigden, Spike Marshall, and Michael Shaver

George: Alright, gents… it’s on. I’m probably gonna sit this one out since I haven’t had the chance to catch either Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance or Sympathy for Lady Vengeance (shit, I barely caught Oldboy about a week ago), but I probably will interject with a lame joke here or there. But just to start, here’s a stupidly simple question that’ll hopefully snowball into a meaty discussion: Which film in Park’s "Vengeance Trilogy" did you enjoy the most?

George: Alright, gents… it’s on. I’m probably gonna sit this one out since I haven’t had the chance to catch either Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance or Sympathy for Lady Vengeance (shit, I barely caught Oldboy about a week ago), but I probably will interject with a lame joke here or there. But just to start, here’s a stupidly simple question that’ll hopefully snowball into a meaty discussion: Which film in Park’s "Vengeance Trilogy" did you enjoy the most?

Steve Atencio: I’m still not sure about my answer. There are pieces from all films that I really like. I was thinking about Mr. V and I felt sorry for those poor people. Everything that happened was because of an accident. Lives can be destroyed in a matter of minutes because of an accident. It’s a simple concept, but he carried it through, showing how many things can be related. It’s like a Seinfeld episode. The characters keep screwing up and screwing each other up and in the end they’re all fucked. That’s a simplified way of looking at it, but there it is.

I really like all three films, and I really like how Park can get such great performances out of his actors, even in the small roles that they may have. I even listen to the soundtracks a lot, such great music.

Michael Shaver: I’ve only seen two of his films, Mr. V and Oldboy, but I have to say that I liked Oldboy the best. I’m not entirely sure why. Maybe it’s because it’s the first film of his that I’ve seen or maybe it’s the energy that it had. I thought that Mr. V had the better ending, though.

Steve Atencio: For me the ending was out there. I think I was as in disbelief as the character getting stabbed. He didn’t believe the girl’s warning, and now here he was getting killed over it. I guess he deserved it, but it was still screwed. Everybody paid in that film; no one came out unscathed.

Nathan Wishart: After seeing all three, it felt like an evolution to me. The first one started off cold and distant. I’ve heard complaints that you couldn’t relate to the characters. That wasn’t the point. You were supposed to sit there in shock while you watched one person’s mistake snowball into something that was really a tragedy of errors. Oldboy has a more interesting plot but the motivations at the end from Lee Won-Jin seem silly.

Lady Vengeance is like the final mix. He’s added the visuals of Oldboy with the colder tone of SFMV. I liked that Park played around with the narrative, it was almost the first two films were like a guy’s idea of revenge but the third film is more of a female’s idea of revenge. It’s no less bloody but there are emotional issues that are far more complex. Add in the mother/daughter relationship and it takes on a different level. The revenge by the parents is also another interesting addition. It won’t bring their kids back but they go ahead and hack Choi Min-Shik to pieces anyway.  Charlie Brigden: In terms of enjoyment, Oldboy for sure. As great as the other two films are, Oldboy is as instantly powerful as Taxi Driver or Fight Club, and it absolutely knocked me on my ass. Those visuals combined with that amazing score really make it, and I kind of see it as a landmark film, especially in terms of Asian movies making it into the western mainstream. SFMV is the one I haven’t seen in a while, but Lady Vengeance was so different from what I thought it would be. I guess from the title, I was expecting a Kill Bill-esque rampage, but the final product left me broken, in a good way. If we’re talking enjoyment, Oldboy is the one, but I think SFLV is the best of the trilogy.

Charlie Brigden: In terms of enjoyment, Oldboy for sure. As great as the other two films are, Oldboy is as instantly powerful as Taxi Driver or Fight Club, and it absolutely knocked me on my ass. Those visuals combined with that amazing score really make it, and I kind of see it as a landmark film, especially in terms of Asian movies making it into the western mainstream. SFMV is the one I haven’t seen in a while, but Lady Vengeance was so different from what I thought it would be. I guess from the title, I was expecting a Kill Bill-esque rampage, but the final product left me broken, in a good way. If we’re talking enjoyment, Oldboy is the one, but I think SFLV is the best of the trilogy.

Nathan Wishart: Does anyone feel the themes of revenge and how it destroys people’s live are handled in a complex manner or just not well at all?

Charlie Brigden: I don’t know if "complex" is the word I’d use, but he definitely uses it in a way to raise discussion. I think what’s interesting is the way the revenge is presented in terms of relation to the characters. Oldboy is almost a big tragic comic book, and while Oh-Daesu’s plight is fucked up, you never feel like it’s directed at you, whereas SFLV takes it to the limit and asks you, ‘what would you do in that position?’

Especially using such a topic as child killing. The way it’s presented, with those harrowing videos, really does a good job of how I’d imagine it to be, not that I ever could really know unless it happened to me. The emotion versus the logical thinking, and how with those images, the emotion just completely takes over, and that ‘do I or don’t I?’ emotional dilemma is brilliantly presented in the film with the parents.

Nathan Wishart: I agree on the dilemma the parents face when they’re presented with the option of killing the man who destroyed their lives. I guess one theme Oldboy did raise is what happens when you’re revenge is complete: Where do you go from there? Do you feel satisfied? Do you still feel empty? It’s the same question that’s raised in Lady Vengeance only Geum-Ja manages to find redemption at the end in the form of her daughter. I also think Choi Min-Shik’s very thinly characterized villain was meant to be more of a symbol than an outright character. I think Park was saying there are some people who are just evil and there’s no explaining it whereas in the previous two installments there was always a motive.

Charlie Brigden: I agree that Choi is a symbol, but I don’t see him at all as being an explanation for people just being evil. I think that’s too simple a term for someone like Park to be involved with, although in case I’ve misread your intention, I think that he is a good example of showing someone without any kind of real motive, though I think the term "evil" is a bit too fairy tale, or Republican if you like.

Giles Edwards: In all honesty, SFMV is probably the one I’ll end up watching (or importantly wanting to watch) the least and Oldboy the most with LV somewhere in the middle – which is a sadly predictable and self-labeling answer. I’m sure many MB posters will be whipping out Comic Book Guy jpgs with happy abandon. But let me expand on that by saying that for me that’s purely based on a reaction of the aesthetics of the three, not a reflection of the quality of the pictures, of which I have a hard time wrenching them from the whole trilogy. On that level at least, Oldboy is the most "enjoyable". Certainly LV and MV are much more grueling affairs, impactful in so many more ways that I almost don’t want to dillute the power of them.

Giles Edwards: In all honesty, SFMV is probably the one I’ll end up watching (or importantly wanting to watch) the least and Oldboy the most with LV somewhere in the middle – which is a sadly predictable and self-labeling answer. I’m sure many MB posters will be whipping out Comic Book Guy jpgs with happy abandon. But let me expand on that by saying that for me that’s purely based on a reaction of the aesthetics of the three, not a reflection of the quality of the pictures, of which I have a hard time wrenching them from the whole trilogy. On that level at least, Oldboy is the most "enjoyable". Certainly LV and MV are much more grueling affairs, impactful in so many more ways that I almost don’t want to dillute the power of them.

Whether that’s because of the wringer that CWP puts his characters through in the Sympathy pictures (though let’s face it, Oldboy is hardly The Band Wagon) or perhaps – and this is my gut feeling – Oldboy is more of a stylistic attack on the viewer – appropriate, given its manga origins. Mimicking the emotive experience Oh-Desu’s gone through, it’s about perception and the gaze and voyeurism and necessarily puts the viewer (and their empathy) in a less precarious position than the Sympathy pictures – who’s titles at once declare the pity needed from the audience, but also something that the filmmaker perhaps has for them, knowing what he’s putting them through. The more formal style of SFMV, and the less baroque nature of LV after Oldboy‘s madcap antics, suggest to me at least that, perhaps because so many of his characters in these two pictures are less "guilty" than those in Oldboy, that the audience’s empathy is heightened and CWP is able to play on that jeopardy far more brutally and intrinsically than the more relatively cartoonish Oldboy. It’s almost as if the sheer and palpable joy of technical filmmaking inherent in Oldboy‘s structural and narrative trickery renders it a more "rewatchble" experience. Though the raw pain which the characters go through is laid as bare on the screen in Oldboy as is it in MV and some parts of LV, those latter two pictures push that human (and thus empathisable) quality to the forefront, confrontationally, purposefully. CWP’s undeniable mastery of the language of cinema is audacious and breathtaking when given full reign, but his more "flashy" affairs (Oldboy, parts of LV and stretching back to JSA) inevitably lack the blunt, absurd realism of MV. While that doesn’t make MV more fun to watch, I’d argue it gives it a slight edge in quality, objectively speaking.

That Oldboy is about a fully grown man not a woman or child (Mido aside, and she’s technically an adult) may have a lot to do with the assessment of the pieces and the re-watch – I wonder how famously vocal exponent of female-peril Brian De Palma ranks these pictures.

That Oldboy is about a fully grown man not a woman or child (Mido aside, and she’s technically an adult) may have a lot to do with the assessment of the pieces and the re-watch – I wonder how famously vocal exponent of female-peril Brian De Palma ranks these pictures.

I like the observation about Seinfeld and the almost comic inevitability of the sequence of events that spirals out of control. And of course I guess Seinfeld itself springs from good dramatic tragedy (there’s some theory, that I subscribe to, that all good sitcom is merely tragedy with a slightly different slant and less realistically-impactful outcome). As does Film Noir, which universe I think all these film’s reside firmly inside of – which is perhaps another discussion. And if Oldboy is the gimmicky brilliance of Dark Passage, is LV is the quiet majesty of Mildred Pierce and SFMV is the catastrophic misanthropy Out of the Past. Dark Passage or Mildred Pierce I’ll watch most, but I can’t deny the overriding status of the latter as king. And so it is with the Vengeance trilogy.

George: Giles makes me feel intellectually inadequate.

Charlie Brigden: I feel like Forrest Gump.

George: At least my cock’s still huge.

Nathan Wishart: It makes sense that you’d watch MV the least. That film is like an endurance test, when it’s over you’re finally glad you got through it. The film noir comparisons are an excellent point though. I haven’t seen either Mildred Pierce or Out of the Past so I can’t make the comparison, but I have seen Dark Passage and I do agree that DP shares a lot more in common with Oldboy than I previously had thought.

I think lack of motive is probably a better explanation for Choi Min-Shik’s character. I said "evil" because of his seeming lack of anything approaching "good" when one of the parents asks him how he could do something like that, he responds, ‘there’s no such thing as a perfect human being.’

I find it interesting that Geum-Ja planned her revenge for 15 years, but when it came down to actually killing another human being, she couldn’t do it. She shot him in the feet though. I like to think think all three films are about the full range of emotions that come with committing an act of revenge. SFMV is just fury, Oldboy is contemplation and Lady Vengeance is redemption. I don’t know how off the mark I am with those but I find it interesting nonetheless.

I find it interesting that Geum-Ja planned her revenge for 15 years, but when it came down to actually killing another human being, she couldn’t do it. She shot him in the feet though. I like to think think all three films are about the full range of emotions that come with committing an act of revenge. SFMV is just fury, Oldboy is contemplation and Lady Vengeance is redemption. I don’t know how off the mark I am with those but I find it interesting nonetheless.

Giles Edwards: It’s all about emotions, or reactions to action taken, yes. Precisely. On a base level, the trilogy revolves around the futility of revenge. But that’s only the jumping off point (and one that’s been made many times before). What the vengeance trilogy becomes about is the transgressive route that vengenace takes. In none of the pictures is the revenge the straight and noble arrow the protagonists think. That’s the very basic, formal expectation we would expect a revenge picture from Seven Men From Now to Death Wish to take.

But then there’s what happens after that vengeance is embarked upon, and sometimes found. Perhaps not so much in MV – though certainly the clusterfuck of circumstance saws down the goalposts with alarmingly random consistency – but in both Oldboy and LV it’s not our protagonist who ultimately has the drive for vengeance.

I’ve posted before about the now fairly accepted analysis path that Oldboy takes: that the final incestuous-Dae-su twist isn’t just there for twist’s sake, but that it’s the crux – if not the ultimate point – of the piece. The great reveal isn’t the qustion of his imprisonment — that the rumour Dae-su spread was essentially innocuous is irrelevant. Woo-jin even says as much:

"The question isn’t ‘why did I imprison Dae-su’. It’s ‘why did I release Dae-su’"

And the grand reveal isn’t even the answer to that question — that he has ensured Dae-su be sleeping with his daughter by the time the 5 July and the anniversary of Woo-jin’s sister’s death comes around.

And the grand reveal isn’t even the answer to that question — that he has ensured Dae-su be sleeping with his daughter by the time the 5 July and the anniversary of Woo-jin’s sister’s death comes around.

No, the grand reveal is that we have been watching a revenge picture where we have assumed it is Dae-su who is the man on the quest for vengeance. When all along it has been Woo-jin who has be seeking his revenge. That’s the brilliance of it. That Woo-jin goes to such diabolical lengths to secure vengenace on what was an innocuous comment by a youthful Dae-su makes the whole story even more desperately tragic and depraved. I don’t see who anyone could find anything unintentionally hilarious about it. It’s utterly poetic and embraces the themes of duality that the monster/Dae-su hypnotic split at the end symbolises — which is actually a diabolical choice in itself: admit the truth to your daughter and live with the consequences with only the pyrrhic notion of having done the right thing to comfort you, or willingly, consciously before the hypnosis, submit to blissful ignorance in a depraved relationship for the rest of your life.

In LV, CWP takes this further I think, in that we KNOW, at least a fairly short time into the picture, that it’s not really the vengance of Guem-Ja that we will be following, but her desire – we find out – for vengeance on behalf of those parents who were wronged. Again, it’s not who we expect that’s getting revenge and the crux of the piece thus rests on WHY it’s not that expected person. So then these films come to be about the culpability of guilt, but more importantly the culpability of revenge. Who should take vengeance, and when, and why? That’s interesting.

That vengeance is a self-defeating proposition is a fairly obvious tool in cinema by now. But in suberverting how that is represented, by making the about why that is so, and whether that dilemma matters to the characters, or whether it should matter, Park makes these pictures so much more thematically rewarding and discursive. That it’s as much about the crime that has been committed on BOTH sides (Oh Dae-su is technically innocent of any crime; the parents Guam-ja helps think they’re entitled to dish out murder – is either position truthful? Is either position untruthful?) is yet another reason these pictures are important. Sure, it’s something arthouse cinema has been doing for a long while, but pushing it into the relative maintream, and specifically a certain genre of cinema, is why I mark CWP’s work out.

Perhaps only Michael Haneke’s Hidden has provoked as many questions as it has answered in the same way as CWP’s pictures (especially the latter two) in this trilogy. Indeed, Hidden (far more complex and transgressive by the way – good as CWP is he’s still bound to genre somewhat) and Oldboy would make for a compelling double bill now that I think about it.

Nathan Wishart: Michael Haneke immediately came to mind when I was thinking of SFMV.

One of the parents asks himself the question, ‘Will this bring our children back?’ right before they wade into Choi Min-Shik with abandon, so I guess the overwhelming desire for revenge ultimately overcame them.

Going back to SFMV, I remember a review stating that the characters actions were beyond their control which I think is false. It only took one major decision by Ryu to set the whole domino effect in motion, but that was hardly out of his control. He just couldn’t wait any longer, which is understandable, but the decision still lied with him and him only.

Going back to SFMV, I remember a review stating that the characters actions were beyond their control which I think is false. It only took one major decision by Ryu to set the whole domino effect in motion, but that was hardly out of his control. He just couldn’t wait any longer, which is understandable, but the decision still lied with him and him only.

It’s in direct contrast to the main characters of Oldboy as Oh Dae-Su has no direct control over his destiny, it was decided by Woo-Jin from the moment Oh Dae-Su left the orphanage. LV is along the same lines as SFMV; her character chooses a path due to her circumstances and ends up paying for it, only there’s redemption for her in end.

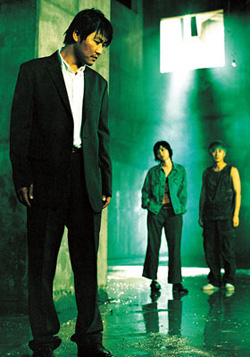

Spike Marshall: The ending to Mr. V is a hard one to pin down. I think it’s wonderful because it completely defies the cold blooded, near cynical nature of the film, but I can see where a lot of people would be put off by the conceit. It seems like a weak get out clause, but it serves to show that each action has a potential ramification and to have Chairman’s Park’s torture not be punished wouldn’t ring true.

I honestly think that Mr. V is the best of the trio in terms of narrative. I cared a lot more for Ryo and Park than I did for Lee Woo Jin and Oh Dae Su. However, I think its visual style, while beautiful, looks like almost every other modern Korean drama: grainy, rainy and reflective. Oldboy, on a purely visual, auditory and pure characterisation level, is a much more interesting film.

Giles Edwards: Okay, another track: Park’s use of music is astonishingly assured and emotive. I’m talking more the latter two here – as the first is more powerful for what you DON’T see and hear (the lead is deaf after all). Baroque music accompanying baroque style, but it’s so much more than that. The classical music Park chooses is itself composed of, to purloin Mr. Tuffnell’s quaint phrase, "simple lines intertwining", yet creates a dizzingly complex whole. It seems the perfect match for Park’s sensibilties.

Steve Atencio: The music is something that has stuck with me. Park seems to know so well when to use it or not use it, and then to use themes that play so well with what he’s showing us onscreen. I don’t know if it’s Park that is making these creative decisions, or if it’s the composer that should get the credit, but the music seems to play so well with what’s onscreen.

I think I can agree with you guys about the merits of each film. Oldboy was a leap forward in style from SFMV, and he changed the look a little again in SFLV. I really liked the looks he gave Guem Ja, especially the black raincoat. With her standing in the background in the final scenes, it zipped up all the way, it reminded me of an executioner, which I guess she was.

I think SFLV hit me the hardest mainly because I have kids. The fear of one of my kids meeting a man like that, a sociopath, is probably the greatest fear I carry around with me. The thought of your kid suffering in a situation like that would make a parent feel so helpless. I can understand the parents and their plight. If put in the same situation, I don’t know what path I would walk.

I think SFLV hit me the hardest mainly because I have kids. The fear of one of my kids meeting a man like that, a sociopath, is probably the greatest fear I carry around with me. The thought of your kid suffering in a situation like that would make a parent feel so helpless. I can understand the parents and their plight. If put in the same situation, I don’t know what path I would walk.

Giles Edwards: I can’t imagine him not having a larger hand than most in many of the creative decisions going on. As a director he has such an imprimatur across the series, that his guiding hand – along with his selecting of some truly talented collaborators – is surely the key to the rewards therein. He’s a naturally gifted artist that much is obvious. I know, however – and this is pretty charming – that he does nothing without running ideas passed his wife, who he claims is his best and most trusted critic. This is something I think is fascinating, given the female point of view (or lack of in some cases) his pictures possess.

Steve Atencio: That’s a cool little fact. I guess what they say about a woman behind every successful man holds true here.

Spike Marshall: This may be utterly wrong but I think it says on the Oldboy DVD that Park was actually heavily involved in the scoring process. Which would make sense because I don’t think I have a heard a soundtrack that so perfectly fits a film like Oldboy‘s in a long while.

The fact he receives input from his wife probably explains one of the reasons I like his work so much as well. At times Asian cinema can seem pretty misogonistic whether by choice (pick any major Mizoguchi movie) or just because the director has no idea how to use women properly. I’d say out of the current crop of high profile Asian directors, only Park and Takashi Miike seem to give women a serious role in their films.

Nathan Wishart: That fact about him running ideas past his wife is interesting and adds another layer to the films. Seeing the way the infamous sex scene between Oh Dae-Su and Mido was shot, I’m more inclined to believe his wife had some definite input there. I liked that they actually made it look realistic from Mido’s point of view; it was painful for her but she endured until the pain turned into pleasure. That’s something you don’t find in films often.

The music though has been great throughout. The minimalism of MV to the mix of classical and modern sounds in Oldboy to the baroque sounds of LV, it’s just an amazingly rich series of scores and worthy of every award imaginable. The use of Vivaldi’s ‘Winter’ is chilling in Oldboy and Vivaldi again in LV, although in a more playful way.

Giles Edwards: I guess the most obvious other element to discuss, that perhaps springs from the nugget about his wife, is the moral thrust of the trilogy.

They’re obviously all very grounded in an intensely personal worldview (of the characters, of Park, or at least of Park’s projection when writing about "his" Seoul), nominally eschewing – and sometimes outright ridiculing – religion, government and societal constraints. Yet on the surface these pictures seem to spring from very traditional moral frameworks. They obviously jump off from those points to start far more thorny dialogues within each film. That’s something I really like and something I suspect would be diluted with any kind of western remake, for instance. They don’t moralise, but they provoke moral debate. That’s great. You can imagine the either straight faced or ersatz-ironic version of MV and LV with their Old Testament eye-for-an-eye dilemma. You can also imagine the soft-peddled resolution of those stories. And obviously Oldboy‘s final ethical bombshell – tell your daughter and live with the pain or purposefully bury the incest within yourself and carry on to let her be none the wiser, YOU DECIDE! – is a showstopper of a debate itself.

You can imagine the either straight faced or ersatz-ironic version of MV and LV with their Old Testament eye-for-an-eye dilemma. You can also imagine the soft-peddled resolution of those stories. And obviously Oldboy‘s final ethical bombshell – tell your daughter and live with the pain or purposefully bury the incest within yourself and carry on to let her be none the wiser, YOU DECIDE! – is a showstopper of a debate itself.

As I say, I really love that there’s no real resolution to these events. There’s an ending to each story but never really any closure. Even when Guem-Ja walks away from the classroom at the end of LV, she’s still getting her vengeance and letting the parents "do unto another". Which suggests her moral culpability (in any real world). There’s sense of sad resignation which she displays that suggests it’s a struggle for her. And the audience, too, have obviously and bluntly been primed for this bitchin’ payback. So when Park so slyly denies Guem-Ja and both the viewer of the film and the voyeur of the film – a big distinction in Park’s pictures I think, testament to the levels of engagement he invites (allows?) in his audiences – of a view of the violence, that’s a real point made well. It reminds me of the opening of Alejandro Amenabar’s Thesis when the audience is primed to see the body on the train tracks, but it pulled back at the last second. There and here, I think we’re all manipulated into wanting to see that violence. Not "dog-headed man getting shot" fantasy violence, but dreadful retribution. The reaction we can see in ourselves when we don’t is a fascinating position for a filmmaker to take. Park’s not the first, of course, but he does it so very well.

And I know one regular poster on our message boards (a great, intelligent guy) who flat out hates that kind of moral manipulation that Park indulges in. And he’s no prude. But that kind of reaction from genre fans is kind of fascinating and provocative to me.

George: If he means DOOM!, I’m packing and moving to Siam.

Spike Marshall: It’s the strength of the film that whenever I hear Vivaldi my mind always snaps back to Oh Dae Su’s attempt at amateur dentistry. It is such a chilling scene and I think the reason is because, up until that point, the film has been almost playful. I’m not saying that forced imprisonment is exactly laugh a minute, but Oh Dae Su’s commentary, his grin when the jumper meets car, and his confrontation with the gang of youth doesn’t really prepare the audience for someone getting their teeth ripped out by a hammer.

Nathan Wishart: I don’t usually cringe but whenever I watch that scene with the hammer and the guy’s teeth, I look away. Just painstakingly vicious.

Giles Edwards: Contrast that scene with a similarly constructed one (it’s ALL in the razor-sharp editing) in LV when the chair is pulled away from the child hanging in a noose and we cut to the father of that child falling off his chair in front of the TV screen. That’s what people are talkig about when they speak of Park’s rigid control and sure-hand over his pictures.

Spike Marshall: I think what Giles

says is really interesting in that Park does manage to goad his

audience into wanting acts of violence to be carried out.

A great example is Sympathy for Mr. Vengenace.

Ryo’s act of vengeance is hideously brutal and serves no purpose other

than to take out his frustrations. His sister didn’t die because of the

organ sellers, but he takes the view that they are to blame and manages

to get the audience on his side during the attack.

While this is in itself fairly routine, it’s the sense of horror

after the attack that I think is incredible. Park takes the time to

give the organ sellers a hint of personality, whereas they were ciphers

up until this point, only when their fate has been sealed.

And I think that contrast which Giles also mentions is probably one of the biggest themes in the Vengeance trilogy. Ryo and Park’s near primal reaction to the death of their significant other are wonderful displays of not only raw emotion but calculated symmetry on the director’s part. Both men don’t have the capability to properley grieve and as such they both do the most seemingly logical thing. Ryo buries his sister and takes out the people ‘responsible’ for her death, and Park embarks on his path of vengeance and tries to find a substitute to fill the void.

Nathan Wishart: The contrasts are more visible in the last two films, I agree, and MV is a really just a descent into hell for two men for which there was no return. The only temporary respite was when Park found that young boy and took him to the hospital to be taken care of.

If you were to boil down the moral thrust of the three films, you could probably sum it up as ‘revenge is bad mmmkay’, but that’s only the surface gloss of what Park is trying to put across with these films.

With SFMV, you have three main characters who become trapped in a spiraling web of violence because of one person’s mistake. You have two men at opposite ends of the social order; Park is the president of a large electronics company and then you have Ryu, a deaf mute, who works the night shift at a local factory. The scene where one of Park’s ex-employees cuts himself in front of his daughter, Park gives us an indication of the economic climate at the time. I think the film also provides a descent for Park as he ends up seeing how bad things really are when he finds that ex-employee and his family dead inside a cramped building. His saving of that kid is like a small redemption for Park, but it’s only temporary.

In Oldboy, Chan-Wook takes a simpler look at the idea of vengeance, more specifically how one small thing could have such a catastrophic effect on someone’s life. Lee Woo-Jin is clearly a diabolical villain and his reason for enacting such a revenge makes it all seem so petty, but to Lee, it was a series of events that destroyed his life. Again, it was the act, however innocent that provided the catalyst. To Oh Dae-Su, the comment was innocuous, but to Lee, the domino effect culminating in his sister’s death solidified his vengeance forever. It makes me wonder if he could’ve achieved all that wealth without the desire for vengeance spurring him on.

In Oldboy, Chan-Wook takes a simpler look at the idea of vengeance, more specifically how one small thing could have such a catastrophic effect on someone’s life. Lee Woo-Jin is clearly a diabolical villain and his reason for enacting such a revenge makes it all seem so petty, but to Lee, it was a series of events that destroyed his life. Again, it was the act, however innocent that provided the catalyst. To Oh Dae-Su, the comment was innocuous, but to Lee, the domino effect culminating in his sister’s death solidified his vengeance forever. It makes me wonder if he could’ve achieved all that wealth without the desire for vengeance spurring him on.

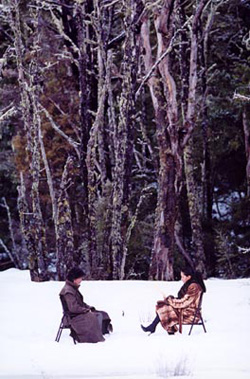

Finally, in Lady Vengeance, the scenario is slightly altered, Geum-Ja is not an innocent this time, her redemption comes from knowing she helped Mr. Baek and her decision to have the parents act out her vengeance for her doesn’t really bring any kind of relief to her soul, it just makes her feel emptier. I found it interesting at the end where the parents are sitting around the table and sharing a moment, that I don’t think any of them truly understand before one of them mentions how it’s snowing outside, and they all head outside and continue on with their lives, almost like they’ve had the last 20 minutes erased from the memories completely. The scene of them waiting in line for their turn was a classic example of Park mixing black humor and pathos.

So, in each film, there’s a catalyst, a decision which propels the characters down a road where they have to decide if it’s worth it. In SFMV, Park doesn’t hesitate at all and he ends up dying at the end. Lee makes a choice to dedicate his life to ruining Oh Dae-Su’s but ends up taking his own life when he realizes how empty it all is. The tragedy is Lee got his revenge but Oh-Dae Su didn’t. And finally, Geum-Ja made a decision to help Mr. Baek kidnap a young child and ends up being framed as a result. Her revenge never really came, and instead, her vengeance was acted through the parents. I don’t know if that’s because she didn’t have the balls to do it herself, but that decision means she’s still trying to come to terms with her part in helping Mr. Baek and, as you said, it’s left unresolved save for her daughter who could possibly provide her with the only real sense of redemption.

Giles Edwards: Interesting notion that though these events are a catalyst for destruction, with that destruction is also some perverse construction that would not have been possible without tragedy – for Lee it’s of wealth and success, for Geum-Ja it’s a family unit.

I don’t know how far you can read that – it’s an impulsive "theory" – and MV doesn’t indicate any lasting triumphs compelled by the series of mishaps. But it’s within the twisted logic of Park’s universe, certainly, for that to be a propulsvie force. It has to get the absolute worst it can be for good to rear its head. And things can only be good once they’ve been exposed to (or radiated with) the bad. The ultimate yin and yang, if you will.

I don’t know how far you can read that – it’s an impulsive "theory" – and MV doesn’t indicate any lasting triumphs compelled by the series of mishaps. But it’s within the twisted logic of Park’s universe, certainly, for that to be a propulsvie force. It has to get the absolute worst it can be for good to rear its head. And things can only be good once they’ve been exposed to (or radiated with) the bad. The ultimate yin and yang, if you will.

One last thing I was thinking about, coming on the heels of the female perspective and contrast discussion: the sex scenes in Park’s films seem, as much as the violence, to ride the line between almost coy and yet caustic, rather in line with the whole poetic/brutish dichomtomy that Park lends to seemingly everything about the trilogy. His use of contrasts here is evident in the way the 3 major sexual scenes of the trilogy range from playfully spiteful/impish in MV to emotionally violent in Oldboy to actually quite stunningly off hand and callous in LV, as Choi quite matter of factly slavers over his dinner, his wife’s general ass area, then back to dinner again.

Thoughts?

Nathan Wishart: Yeah, I’ve noticed this as well. In each film, there’s been one major sex scene with the exception of LV which doesn’t contain any sex scenes with Lee Young-Ae but does contain disturbing sexual acts from other characters.

MV had one interesting sex scene where Ryu and his girlfriend have sex while doing sign language which I thought was quite novel. The one major sexual act between Oh Dae-Su and Mido is handled with tenderness and a willingness to explore it from a female point of view instead of the usual male point of view. Mido originally finds it painful but eventually the pain subsides.

MV had one interesting sex scene where Ryu and his girlfriend have sex while doing sign language which I thought was quite novel. The one major sexual act between Oh Dae-Su and Mido is handled with tenderness and a willingness to explore it from a female point of view instead of the usual male point of view. Mido originally finds it painful but eventually the pain subsides.

LV contains the most disturbing sexual acts such as the one you mentioned plus cunnilingus in a women’s prison. It’s this view of sex from Park that’s most interesting, almost like he can’t decide whether sex should be a painful or pleasurable experience.

Giles Edwards: I mean, I don’t even know what’s really going on in that scene in the kitchen with Mr. Baek, but it’s pretty disturbing.

Nathan Wishart: Agreed, but it’s just there to serve the point that he’s a bastard, plain and simple. There’s nothing redeeming about his character.

I guess to wrap this up this little roundtable, as I stated in the beginning, each film is an evolution of Park’s style from the sparse, unflinching SFMV to the glossy, visual Oldboy and finally to SFLV which feels like a culmination of both styles and the themes that have run through all three.

George: Well, that was ridiculously enlightening, gentlemen. I better get to watching SFMV and SFLV right away. Thank you all again!

Got an idea for a Chewer Column article or op-ed piece? Let me know! Comments, praise, mudslinging, and all that good stuff are welcomed too. Just email me at george@chud.com with CHEWER COLUMN in the subject line.