The strangest thing about Steven Soderbergh’s Bubble isn’t that it was shot on a shoestring budget with non-actors in all the roles, or that it’s being released essentially simultaneously in theaters, on cable and on DVD. It’s that what begins as a meditation on the lives of small town people suddenly veers into a murder mystery.

The strangest thing about Steven Soderbergh’s Bubble isn’t that it was shot on a shoestring budget with non-actors in all the roles, or that it’s being released essentially simultaneously in theaters, on cable and on DVD. It’s that what begins as a meditation on the lives of small town people suddenly veers into a murder mystery.

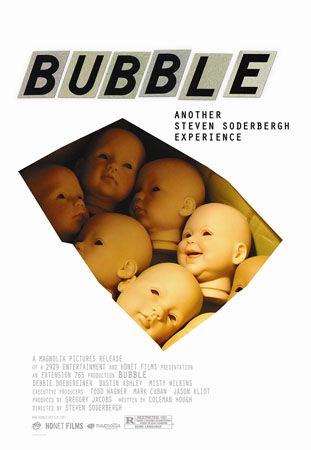

It’s a very sudden shift – for more than half of its running time, Bubble is very quiet and seemingly without much narrative. Martha is a lonely middle aged woman who lives with her elderly father. She works at a doll factory, hand assembling the dolls, and her best (and possibly only) friend is young Kyle, a shy kid who is probably college age. She drives him to work, and to his night job at a shovel factory, and it’s pretty obvious that she is in some way in love with Kyle.

They have their little life set up, and it’s all sent off kilter by Rose, a single mother and newcomer to the doll factory who may not be all she seems. Martha’s worried that the new girl is bad news, and takes an instant disliking to her, especially once she and Kyle go on a date. Meanwhile, Rose’s ex is stalking her, claiming she stole money from him. It all culminates in a murder and police investigation.

I think I liked Bubble best before it turned into Law & Order: West Virginia Unit. Soderbergh had found a tenuous beauty in the blasted landscape of a small town in dire economic straits. He had also found a truthful grace in the lives of these people, the kind of people who never make it into the movies. I felt like the movie was on a pleasant drone level, like a good Sonic Youth or Velvet Underground song (to namecheck two bands the people in Bubble would probably never listen to), where getting to the chorus isn’t really the goal.

Even so, you have to admire the audacity of introducing a procedural aspect to the film. The first half asks the cast to essentially play themselves, having small conversations and telling stories from their lives. It’s when a familiar narrative kicks in that Soderbergh is really challenging these people, and by extension himself. For the most part it’s a success, bolstered by the goodwill we have for the characters from the first part. Still, this is where the non-professionalism shines through – when you ask a non-actor to respond in shock to news that someone is dead, you’re probably going to get a very bad imitation of the very bad performances that pass for acting in major films and on television.

The whole thing is scored with a gorgeous and haunting acoustic guitar performance by Guided By Voices’ Robert Pollard. The spareness is a perfect complement to the skeletal world Soderbergh is partially creating and partially documenting.

Full Frontal is one of my least favorite Soderbergh films – it’s a low budget “experiment” crammed with celebrities, and it’s full of reflexively self-fellating Hollywood nonsense. Bubble is 180 degrees away from that. To me it’s a fascinating look at the blurry lines of reality and fiction (Soderbergh breaks away from his neo-realist take on small town life with a couple of shots of stylized religious ecstasy, and any good murder investigation will have someone lying somewhere in there) that sits on that very blurry line itself. Hollywood is essentially false, so finding falsity there is like finding broccoli in the vegetable aisle. But Bubble looks at small town life and death with both utter honesty and possibly the complete artifice of an outsider’s point of view, with the truth of non-actors using their own lives to construct characters meeting the pretend play of the second half of the film.

For some people Bubble will be an exercise in tedium, but it’s a film whose pacing while deliberate is completely correct. It’s short, clocking in at 72 minutes, and Soderbergh makes them all count. What he does with Bubble is take a concept that could have been the art house version of a sideshow and turns it into something exciting and real. He has five more films like this coming from Magnolia Pictures and 2929 Productions; at least two more will be made like this one. I can’t wait for them.