The double feature is cinema appreciation at its most basic. The mere act of pairing two films together – whether the bond be subject matter, central theme, a certain actor or filmmaker, or something outside-the-box conceptual – causes them to take on a different sort of life. A new relationship is formed with the viewer. You pay attention to new aspects and journey down unfamiliar avenues when you view films through Double Feature Goggles. Even when the linking bond is comically tenuous, the double feature magic is there. And I’m the kind of guy who derives just as much pleasure from creating a double feature as I do from watching one. Aside from amusing myself, hopefully I can give some people ideas for their next movie night.

The Double Feature: Fantasia (1940) and Allegro Non Troppo (1976).

The Connection: An anthology of classical music’s greatest hits interpreted through hand-drawn animation, interconnected with live-action sequences of an orchestra and a host to introduce the pieces.

Film 1: In 1897 French composer Paul Dukas wrote his most famous work, the short symphonic piece The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, which was based on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1797 poem of the same name. In 1937, Walt Disney partnered with the famous conductor Leopold Stokowski for a short animated adaptation of Dukas and Goethe’s works. The project had a very specific goal — Mickey Mouse’s comeback. Mickey had carried Disney (the man and company) to the top of the animation world, but lately Mickey had begun losing his luster. Donald Duck and Goofy had eclipsed Mickey in popularity a while ago. Disney could at least live with that. But by the mid-30’s Mickey was showing up in opinion polls behind characters (gasp!) created by other companies. That can’t have surprised very many people. Mickey is boring. But Mickey was Disney’s flagship character. Walt Disney saw the dwindling of Mickey as an abstract dwindling of the company itself. Mickey needed a boost in the arm, and The Sorcerer’s Apprentice was just the thing. The only problem was the budget on the lavish short swelled to such a large number that Disney realized he could never hope to make his money back selling it as pre-show entertainment. This sent his mind wandering back to something Stokowski had suggested during their first meeting…

Making an entire feature film comprised of short segments based on great classical music. Disney then turned to Deems Taylor, a composer and popular critic (who ended up serving as the Master of Ceremonies in the live-action segments of the film), and together with Stokowski and several members of the Disney animation department, set to work on what was originally less intriguingly titled The Concert Feature.

Looking at Walt Disney’s filmography now, it is rather amazing that Fantasia was only his third feature film — made concurrently with his second film, Pinocchio (both premiered in 1940). Though contextually it makes a lot of sense, as the project reeks of ambitious naivete. No one had thought Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs would work, but it had. Disney must have felt unstoppable. It is this sort of genius in a vacuum that leads great artists/entertainers to make what generally seems like a totally insane move from the outside. It is the same sort of ego-sheltered situation that led Jim Henson to follow up his second feature film, The Great Muppet Caper, with The Dark Crystal. Unfortunately Disney’s grandiose idea (which included adding new segments every few years and continuously releasing a new version of the film, with only the Mickey segment staying in place) went down the same road that most films made in these circumstances do — a great fringe artistic work that is poorly received by the public and loses money. Though, to be fair, part of its failure was due to WWII cutting off foreign markets and the fact that Disney’s engineers essentially invented surround sound (called Fantasound) for the film, which had to be installed into any theater showing the film. Fantasia didn’t actually turn a profit until the film was re-released in the 60’s and advertised towards the drug-using generation as “the ultimate trip.” Saddest though is that Disney himself viewed the film as a horrible mistake. Which, financially I suppose it was, but as a man from the future looking back of the breadth of Disney’s amazing career I think Fantasia remains one of his most monumental achievements, and quite possibly the purest artistic example of the power of animation ever made. It is a shame Disney wasn’t able to create new segments for the film over the years. Although the spottiness of Fantasia 2000 may indicate that the original film was lightning in a bottle, and best left alone after all.

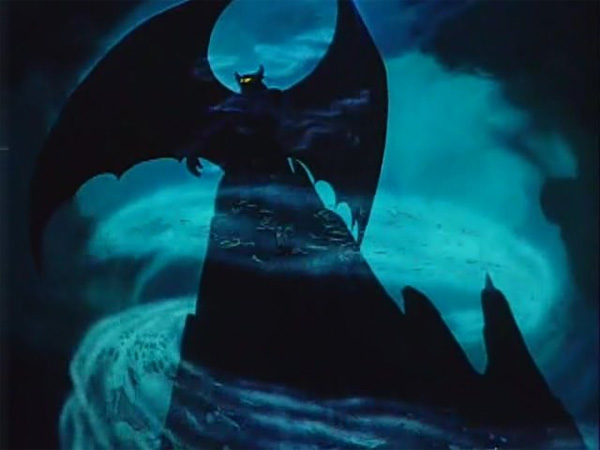

Disney opens boldly. After Deems Taylor stiffly introduces Fantasia to us, the film’s first segment is Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor which has the most blatantly unorthodox animation in the entire film. Unlike the rest of the animated segments, Toccata doesn’t attempt to tell a story or even have characters, but simply utilizes abstract shapes and patterns. One might suspect that some original audience member worried about what they’d gotten themselves into (“This isn’t Snow White!”). But from there the film becomes a surprisingly rich mix of tones. There is the silliness of hippos doing ballet in Ponchielli’s Dance of the Hours contrasted with the steely seriousness of dinosaur life and their disturbing extinction in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. We have the sugary cuteness of frolicking technicolor baby unicorns in Beethoven’s The Pastoral Symphony and the dancing mushrooms in “The Chinese Dance” excerpt of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite (one of Disney’s most adorable creations), and we also have the gothic nightmare of demons and spirits cavorting at the feet of their monstrous winged master in Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain — which aside from being fucking badass, also features possibly the best piece of character animation to ever come out of Disney’s classic period; Vladimir “Bill” Tytla’s rendering of Satan (or Chernabog). Even if the entire rest of Fantasia were awful, it would be entirely worthy of existence purely for the Bald Mountain segment.

Film 2: “Allegro ma non troppo” is a musical instruction that means “play fast but not too fast.” Removing the “ma” creates a pun here basically meaning “not so fast.” Italian animator Bruno Bozzetto’s film was (and still is) advertised as a parody of Fantasia, but that is somewhat misleading and only partially true. The black and white live-action segments are certainly an obvious parody. For one thing, here our Presenter (Maurizio Micheli) receives a phone call from “Hollywood, California,” during his introduction, informing him that another film using Allegro‘s concept was made years ago. And instead of Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra, we have a surly and abusive Orchestra Master (Nestor Garay) conducting an orchestra of chattering old ladies. He also conducts an Animator (Maurizio Nichetti) who is forced to draw the animated segments live on stage, but is increasingly distracted by a growing love for a young cleaning woman ((Marialuisa Giovannini) who is tiding up the theater. It is all quite silly. But that is were the parody stops.

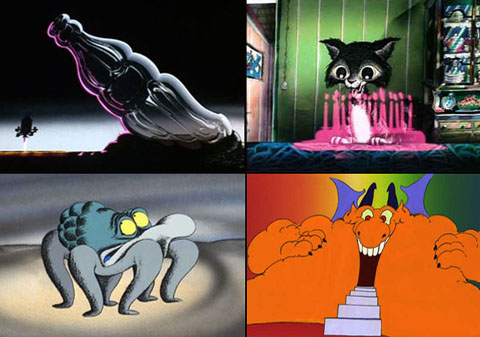

Being called a parody does some disservice to Bozzetto’s work. While Disney’s film may have inspired Bozzetto to create something a bit different and more adult in the style of Fantasia (and let’s remember that Disney Studios wasn’t churning out particularly great films during this period), the animated sequences in Allegro are no mere goof. While some of the segments are silly trifles lasting no more a couple minutes – like a Vivaldi’s concerto featuring a bee trying to eat a meal that is continually interrupted by two humans making out during a picnic – Bozzetto also gives us moments of heartbreaking beauty, like Sibelius’s Valse triste featuring a cat wandering amongst the ruins of an apartment building, sadly remembering all the occupants who used to live there and feed it. Allegro also has two brief moments in Stravinsky’s The Firebird (a musical piece that was rendered very differently in Fantasia 2000; that film’s best segment actually) that seem to have respectively inspired both Bill Plimpton’s How To Kiss and The Simpsons‘s Itchy and Scratchy.

Double Feature Goggles: Allegro Non Troppo is not quite the masterwork that Fantasia is. It never reaches the heights of sheer awe of Bald Mountain, and has more lesser moments. But it nonetheless stands strong as a fantastic work of animation. Allegro had significantly less money and animators to work with, so Bozzetto had to be clever — using abstract or expressionistic backgrounds, where Disney used lush and detailed backgrounds, and using cartoony exaggerated character designs where Disney often sought anatomical realism. Allegro works wonderfully as an antidote to Fantasia. While Fantasia gets plenty silly in parts, it is still a Disney film. Allegro has a youthful subversiveness to it, and not just in the live-action segments; Fantasia certainly doesn’t have a creature made entirely out of boobs anywhere in it. Though, oddly enough, Allegro‘s edgy hipness now feels significantly more dated in 2011 than Fantasia does. The pervasiveness that Disney Studios has had for the past 70 years, and their ability to fairly faithfully adhere to the basic animation style established back in the 40’s, makes most of their older films feel timeless rather than old.

Though Fantasia easily wins the battle of pure animation with Allegro, the Italian film is a better movie. Fantasia has always had a bad rap for being boring. Which, impartially, it is. But that’s the fault of live-action segments that have the agonizingly anemic tone of a NPR program. And despite the fact that the song selection and the ordering of the segments fulfill a very vague thematic arc, the truth is that Fantasia doesn’t really work when viewed as one would a regular narrative feature film or even a regular anthology film. It is a great film, yet it isn’t really a film at all. While certain segments are comfortably digestible to an average filmgoer in a standalone setting, as a beginning-to-end experience Fantasia is probably most appealing to those who truly appreciate animation as an art form. It is masturbatory; animation for its own sake, in a sense. While Allegro‘s animated segments don’t exactly add up to anything more than Fantasia‘s, the live-action segments have a through line, an evolving subplot, and a climax. And aside from providing looney comedy distractions, the live-action segments tend to feed directly into the animated segments, often thematically. Some of the live-action segments even feature animation themselves, such as a scene where the Animator creates a little man on a piece of paper that then moves about the room in a style reminiscent of Sesame Street‘s “Amazing Little Super Guy” shorts. Comparatively, I don’t think I’ve ever watched all the live-action segments in Fantasia since getting it on home video and gaining the awesome power to fast-forward, or even better — chapter skip.

Though all this wackiness in Allegro does have the downside of sometimes sending us into serious segments in an improper state of mind, and giving an air of triviality to the entire proceedings. As bland as Fantasia‘s Master of Ceremonies sections may be, they at least provide something of a palate cleanser.

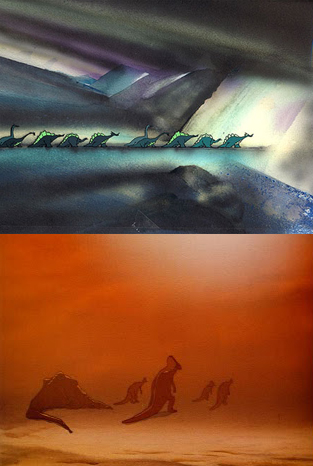

The only animated segment in Allegro that seems to directly contest Fantasia is Ravel’s Bolero, which isn’t so much a parody of Fantasia‘s Rite of Spring as it is another interpretation of the same idea — showing the evolution and extinction of the dinosaurs. Fantasia‘s segment is substantially longer than Allegro‘s, beginning with the formation of the universe and Earth’s evolution from a fiery volcanic wasteland (featuring some truly astounding FX animation) before we actually get to life. Allegro skips all this, whimsically, by having a soda-pop bottle fall from space, from which leaks an ooze that turns into life. Then both feature creatures emerging, eating each other, and evolving. Fantasia uses Stravinsky dynamic and often somber piece to give this progression of life a quiet ominous tone. Allegro uses Ravel’s jaunty march to, well, give things a jaunty feeling. Here evolution is a relentless strange and unstoppable advance, with the soda-pop ooze morphing into a series of bizarre creatures that eat each other and continue evolving until we finally get dinosaurs. Fantasia‘s segment becomes intense and a bit terrifying (for kids), when an unfortunate stegosaurus loses a knock-down fight with a T-Rex. And then rather unsettling when Earth dries up and the dinosaurs are sent marching through an arid desert, dropping like flies from thirst. As Ravel’s Bolero is unwaveringly jaunty, as is Allegro‘s segment. There are no moments of intensity, just strange abstract fun. Both pieces work equally well on their own terms, because they are both going for something wildly different. And the same can be said for the films themselves.

Previous Double Features

The Commitments/The Blues Brothers | The Set-Up/High Noon

The Plague Dogs/Secret of NIMH | The Old Dark House/Dolls

The Fury/Firestarter | Alligator/Q

Where the Buffalo Roam/Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

Mad Love/Body Parts | The Fall/Adventures of Baron Munchausen