BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK

HERE!

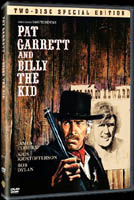

STUDIO: Warner Brothers

MSRP: $26.98

RATED: NR

RUNNING TIME: 115 Minutes (2005 Cut)

/ 122 Minutes (1988 Cut)

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• Commentary by Nick Redman, David Weddle, Paul Seydor and Garner Simmons

• Two cuts of the film

• Deconstructing Pat and Billy

• One Foot in the Groove: Remembering Sam Peckinpah and Other Things

• One For The Money and Sam’s Song

• Trailers

(This is

part of the brilliant new Sam Peckinpah box set. Get to the other

reviews and the artwork evaluation here, or just go buy

the set from Amazon!)

People

who knew Peckinpah call this movie the beginning of the end. For a couple years his movies had

been hit and miss at the box office — Cable Hogue and Junior Bonner died, while

Straw

Dogs and The Getaway found success. He complained that he was castigated

for using violence, but that whenever he left it out, nobody watched the film.

Always a drinker, Peckinpah had gone further into the bottle by 1973, when the

chance to direct Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid came along.

One of

the first scripts Peckinpah wrote was based on the tale, so the offer seemed

like perfect timing. Turns out the timing wasn’t so good after all; MGM was

trying to get that big hotel opened in Vegas, and to keep cash on the books MGM

chief James Aubrey forced a bunch of films to the screen. Pat Garrett was among

them, and it was born way too early.

The film

turned into a battleground between Peckinpah and Aubrey and was almost

destroyed in the struggle. But it’s not as severe a casualty as The

Magnificent Ambersons, and there’s a remarkable film in here still.

The Flick

New

Mexico, 1881. One-time outlaw Pat Garrett (James Coburn) has taken a job as

Sheriff, working for land and cattle interests in Lincoln. He’s been hired to

bring in the outlaw Billy the Kid (Kris Kristofferson), his old friend and

spiritual son. Garrett doesn’t want anything to do with the cattle barons, but

he sees the times changing and doesn’t feel like he’s got much choice.

Producer

Gordon Carroll has described the movie as a chase film where "a man who

doesn’t want to run is being pursued by a man who doesn’t want to catch

him." I can’t do it any better. Garrett, for his part, spends as much time as possible wandering New Mexico, putting off the end and giving the Kid a chance

to bugger off. Billy doesn’t believe that anything is really changing. He goads Garrett towards the confrontation, eventually rushing towards it himself

knowing full well how it will end.

Even near the end, the Terror of the Snake Street had the power to intimidate.

Their

movements are like a dance. These one-time companions circle around each other

until there are no more moves to make. Most of their friends become casualties

of the performance, sacrificed to save one or the other, put down along with

every myth of the west. Slowly and deliberately Peckinpah tears down any heroic notion that you’ve seen under a cowboy hat. What’s left is a grim sketch

of civilization, a social order that hangs by a thread made of money. These are the good old

days that Pike remembers in The Wild Bunch, and they’re violent and dirty, as

were the days before.

Despite

the grime, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is also Peckinpah at his most poetic;

the major sequences are arranged more like Cantos than plot points. Each episode

sketches a specific confrontation which adds to the sense of desolation and

inevitability as Garrett and Billy draw closer to one another.

It’s a

nihilistic piece of verse. In Peckinpah’s eyes the law means nothing; it’s a

totally relativistic state of affairs determined by people with money and land.

Law isn’t good and evil, and it’s not something that’s part of a man. Billy has

been law once before, and Garrett’s current status as law is only a kind of

manipulation and provocation.

.jpg)

The only law is young love.

The only thing that matters is loyalty and friendship between men. But

the demands of law and civilization call upon men to sell out those ideals in

order to survive. It’s an almost unbearable way to look at the world; only a

camera eye ironically attuned towards beauty softens the blow. The film is as

grimy, if not more so, than any of Peckinpah’s westerns, but the work of cinematographer

John Coquillon can suddenly become strikingly gorgeous.

Coburn is

phenomenal as Garrett. His face doesn’t look this weary even now, and he uses

it to reveal a tide of impulses that are always at war behind his eyes. Coburn

never loses control, but you can almost see Garrett walking on the brink of

throwing everything away.

The

baby-faced Kristofferson, meanwhile, makes Billy into an inscrutable figure.

He’s charismatic and amoral, the sort of sociopath who’ll genuinely smile as he shoots you in the back. Kristofferson doesn’t play the Kid for any

sympathy, and Peckinpah never offers it.

.jpg)

"You sure this isn’t the one I was pissin’ in last night?"

Then

there’s Bob Dylan, making his debut as a newspaperman turned killer named

Alias. I still feel a twinge of resentment when I see him in this movie; there

are guys like L.Q. Jones and Harry Dean Stanton dressing the background while

Dylan slides through the fore. Stanton would have been marvelous as Alias, and

Dylan is often just…weird. He’s not lost, but only because Dylan has his own

unique presence.

Alias

soon enough has Billy’s ear, and he’s the gunfighter’s chronicler (his ballad about Billy is

on the soundtrack) but also goads his subject into action. It’s probably happenstance rather than intent that links Dylan’s real work so strongly to his onscreen character, but that little dose of meta does add to his effect. Peckinpah evidently resented the heavy use of

Dylan’s music on the score, which probably sounded a lot more strange then than

now, when a loud musical overlay might be present in any given film.

.jpg)

"I know I got somethin’ womanly in here somewheres…"

Though

the songs at times are given too much dramatic weight to pull, there are

moments of salvation. Dylan’s ballad about Billy is tinged with irony.

"They say Pat Garrett has got your number," it goes. That’s the truth

turned around; Billy’s got Pat’s number, and he knows it so well it might as

well be tattooed on his arm. ‘Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door’ almost sounds fresh

when it becomes the backdrop to the death of Slim Pickens, playing a sheriff callously

sacrificed by Garrett for what amounts to nothing.

That

death is one of the most heartbreaking scenes in the film, and in any western.

It’s the crystallization of the movie’s notion that all this killing is nothing

but arbitrary, senseless waste. It’s hinted at earlier in the movie when Billy

tells a story about a killing instigated when a man’s boots were stepped on.

But the theme comes home cold when you watch Pickens die. Peckinpah’s offered

that viewpoint before, but nowhere is it as rending as you’ll see here.

When I

sit back and look at the film as a whole, it’s the spitting image of a flawed

masterpiece. The tone is laconic and meandering, but Peckinpah is more vicious

than ever; this is the film where his skills as a popular filmmaker best

colluded with his own dismal view of the 20th century.

8.6 out of 10

The Look

Both

versions of the film look great, but the 2005 cut seems to have received an

extra level of polish; some of the scratches and minor damage that mars the

1988 version have been removed. In all, the image is clear and extraordinarily

dense. Maybe I’m crazy, but I see resonances of this movie all over the place

— Han Solo’s costume looks just like Billy’s, and Coburn’s face, ruddy and

shadowed as it is here, looks like it was the basis for Bernie Wrightson’s art

in the early ’70s. A reach? Probably, but the film is beautiful regardless.

9 out of 10

The Noise

Much like

the image, the sound is all clear and very effective. Dylan’s music has a

really full, rich sound, and the effects, especially gunshots, aren’t given too

much of an exciting action movie zing.

9 out of 10

The Goodies

Ok, so

what’s all this nonsense about the 2005 cut and 1988 preview cut each of which gets a disc in this set? When

originally released, the movie was something like a massacre. After showing a

160 minute rough edit, Peckinpah and his editors were given only a month to turn

in a real preview cut. 124 minutes were delivered; typically there would be

time after that delivery to refine the edit.

That

opportunity and the film as a whole were taken away from him, and MGM cut the

movie for release in a way that emphasized action and little else. The prologue

was missing as were several other segments — almost 20 minutes.

.jpg)

At Brokeback Mountain’s busiest saloon…

The 1988

Preview Cut was an attempt to recreate what Peckinpah previewed before the film

was taken from him. Aside from an interlude between Garrett and his wife, this

cut is identical to the 124-minute preview from ’73; this one runs 122 minutes. It’s thought of as the

last cut that had his stamp on it, though even that is an exaggeration. It’s far superior to the theatrical release.

The 2005

cut was made by Seydor and with input from Peckinpah’s editors and the other

biographers, and is an attempt to create something that Peckinpah might have

done had he been given the opportunity to refine the Preview Cut. Though seven

minutes shorter than the 1988, it feels more detailed, and Garrett’s tense conversation

with his wife has been reinstated. The removed footage is almost entirely from

scenes that are still in the film, and the cuts by and large make the scenes

more sharp.

In an

ideal presentation, this would be like Criterion’s Brazil set, and we’d have

the theatrical cut in this box alongside the other two. I prefer the 2005 cut,

but really appreciate Warner Brothers including the 1988 in full so that we’ve

got a much more whole picture of the movie and what was done to it.

.jpg)

Fine! When the time comes, I’ll do Blade 3!

Both

versions of the film feature a commentary track with the same quartet from the

rest of the set. Listening to these tracks made me want to watch the original

theatrical version even more, as it’s referred to endlessly. With so much more

time to talk, things get more digressive, but there’s also a lot of joking and

speculation, which can be fun from guys who have such detailed knowledge of the

man and movies.

Deconstructing Pat and Billy features interviews with Paul

Seydor and Katy Haber, Peckinpah’s assistant and companion through most of the

’70s. It’s a great condensation of the troubles Peckinpah faced, and his

intentions for the film.

One Foot in the Groove:

Remembering Sam Peckinpah and Other Things is a nice sit-down with Kris Kristofferson and

friend Donnie Fritts, who had small parts in this film, Alfredo Garcia and Convoy.

It’s as broad and digressive as the Stella Stevens piece on the Cable Hogue

disc, but it’s a little more entertaining with two people talking. One For The Money and Sam’s Song are a

pair of tunes performed by Kristofferson and Fritts.

9 out of 10

Overall: 8.9 out of 10