BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

STUDIO: Warner Bros.

MSRP: $19.98

RATED: NR

RUNNING TIME: 73/71 Minutes

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• Commentary on each film

• Trailers

Cat People

If

Universal horror kept kids happy in the early ’40s, RKO and Val Lewton provided

sophisticated adult escapism. Despite titles that promised exotic and gruesome

images, their horror was pure class. Of Lewton’s productions for the studio, Cat

People is his first and best, and the sequel is a darkly idiosyncratic,

if less successful family drama.

The Flick

Lewton’s

first film is an unparalleled success. Later, The Seventh Victim would

demonstrate the producer’s facility with an intricate story. Cat

People, on the other hand, is a picture of elegance and simplicity. It

combines the uncertainty of urban romance with perfectly crafted shocks to

create a brand new, shadowy horror that blew Universal’s stuff off the screen.

.jpg)

"I really hope she doesn’t expect me to live up to that."

The

gorgeous Irena is, as they say, a minx. She’s a Serbian immigrant who sketches

for the fashion industry. She stalks the city zoo, contemplating the large cats

and a diabolical fate she both fears and longs for. Irena is descended from a

group of people once driven out of their village for witchcraft and evil. She

likes the dark; it’s friendly. Actress Simone Simon’s alluring, accented lisp

lends a girlish appeal; dark eyes and worldly presence give Irena an unearthly

gravity.

Oliver

meets Irena at the zoo and tumbles like a picked lock. Easy to see why; he

leads a dull life as a design engineer at a shipbuilding firm. He’s only got

Alice to look at. She’s the sort of New York girl that knows where to get a

great martini or superb bisque, but Oliver’s more interested in the mysterious

type.

.jpg)

"That’s a cigarette and this is vodka…the good old days are great!"

Irena is

definitely that. Their courtship is brief, but marriage isn’t what Oliver

expected. Irena is haunted by tales of her supernatural past. She fears

intimacy could unleash evil she fears lurks within. Consummation isn’t on the

menu. Ready with a shoulder to cry on is Alice. Soon enough nature takes its

course and Irena is given reason to let jealous evil reign.

With Cat

People, Val Lewton and director Jaques Tournier create fear out of the

mundane. The script, by future Lewton regular DeWitt Bodeen, drew a layered

story out of a corny title. There are no real monsters; the film mocks genre

icons like the silver bullet. Armed with no budget and standing sets, Lewton

and co. laid out a romantic triangle full of jealousy, fear and a subdued,

predatory sexuality. Nothing could have been further from the horror a ’40s

audience expected to see, and the film stands out even today as unique and

groundbreaking.

Lacking

money for effects, Tournier and Lewton relied on sound and suggestive lighting

to shock. Most memorable is Alice’s nighttime swim in a hotel pool, where she’s

menaced by horrors that would have been laughably cheap had Tournier shot them

head-on. Roy Webb’s dexterous score always drives the picture forward, but

there the soundtrack features only naturalistic effects and Alice’s screams.

The choice flew in the face of established technique, and the scene is a

landmark.

.jpg)

"Dammit."

Flowing

through the setpieces is a trio of characters that embraces familiar foibles,

weaknesses and hopes. How could anyone not sympathize with Oliver, once he’s in

the thick of his problems? In response, Alice’s behavior is complex; as a

friend and would-be lover she’s far more real than almost any genre lead. While Simone Simon is an iconic anti-heroine,

Kent Smith and Jane Randolph deliver oddly naturalistic turns as Oliver and

Alice. Cat People never shortchanges its people in favor of made-up

monsters, and the cast uniformly delivers some of the best b-picture acting

you’re likely to see.

Though it

relies on romantic overtones, Cat People is shaded with sexual

unfulfillment and fetishism. Visions of death prevail and Irena’s outfits and

apartment imply a deep acceptance, even enjoyment of her fears. As Joseph Breen

still held American film content in his repressive iron fist, the content is

remarkable. Today Arrested Development is getting away with murder. Fifty years

ago it was Lewton and Cat People.

Yet those

dark aspects don’t overwhelm the sensitivity that is Lewton’s key contribution.

No matter how bizarre Irena’s behavior, or how moodily the picture was lit,

Lewton’s script revisions ensured that characters expressed real concerns

through dialogue as credible as anything in an A-list picture. In some ways

more so — even cameo support players project a dignity and individualism that

flaunts mid-century standards.

.jpg)

I’m jealous of this, since I only dream in Hanna-Barbera.

The film

is also the introduction of Dr. Lewis Judd, Irena’s psychiatrist and a

character that turns up in Lewton’s other best film, The Seventh Victim. Tom

Conway plays the utmost urbane intellectual, the perfect counterpoint for the

film’s current of mysticism and fear.

Judd

represents Lewton’s best instincts as a guiding creator. He’s a predatory,

selfish man with private motivations, but not without the ability to recognize

genuine need in others. Whether he decides to capitalize on that need or to

offer genuine help is a matter of whim, and that makes him entirely whole. In

his two films Judd becomes one of the best supporting characters of ’40s

cinema.

I do wish

his introduction didn’t feature filler dialogue about psychiatry and childhood.

Tournier seems to feel the same; Judd’s entrance is the only dead spot in the

film. It’s staged with all the ingenuity of an Ed Wood production. You can

almost feel Tournier’s desperation to be done with the psychobabble.

The face of a man about to sleep alone on his wedding night.

Who can

blame him when there’s great stuff to chew on, like Alice’s walk home through

Central Park? As in the pool scene, the park walk used nothing but suggestion

and clever editing to create a fiercely oppressive air. You’ve seen it in a

thousand horror films since, including almost every effort from Lewton.

Cat People was a triumph, and it nearly

erased the stigma that Orson Welles had drawn over RKO. It made the careers of

most of the technical artists involved with the film, and began Lewton’s

classic run of modern psychological horror. Nine years later, Val Lewton would

be dead of heart failure.

Curse of the Cat People

Less than

two years after Lewton saved RKO, the studio threw out another absurd title and

demanded a sequel. Lewton accepted, but seemingly with even less enthusiasm for

the title than in the past. The script he commissioned was accordingly even

farther from a stock horror film than the original. It’s far from his best, and

not at all the sequel you’d expect. But Lewton never delivered the expected,

and moments of Curse

have their own beguiling charm.

The Flick

Oliver

and Alice return, and they’ve got a daughter. Amy is a dreamy, isolated little

girl. She invents fantasy playmates and is distanced from real children. Though

the family has prospered (and moved to the suburbs) the spectre of Irena

haunts them. Oliver fears Amy’s inner life, and encourages her to be a regular

child.

Eager to

please her father, Amy tries. But the neighborhood children reject her, and she

finds unlikely refuge in a dark, rambling mansion haunted by old Julia Farren,

an aging actress. Sunset Blvd. wouldn’t appear until six years later, but in Julia

Dean I could see only Gloria Swanson. Like Swanson’s Norma Desmond, Mrs. Farrin

haunts her old manse, lost in memories of old performances and fading fame.

MILF!

Mrs.

Farren pays great attention to Amy, to the consternation of her own daughter.

She gives the girl a ring, upon which Amy wishes for a friend. And who appears

but Irena, now shorn of the dark fur she once wore as a cat woman. Now she’s a

ghostly fairy in a flowing gown. She and Amy enjoy one another’s company,

frolicking in the yard and celebrating a serene, secret Christmas apart from

the family.

I like

Ann Carter’s quiet, restrained work as Amy, and she keeps the film from

spinning out of control. When it works, the credit is largely hers, for

offering a view into a childhood at odds with expectations.

Contrasting

Carter’s work are the three adult leads, all of whom are shades of their former

selves. Kent Smith and Jane Randolph deliver the sort of stiff work you’d

expect from a budget sequel. When Simone Simon appears she doesn’t seem to know

what to do, and Irena becomes little more than window dressing, de-clawing the

haunting image she left behind.

.jpg)

After a smart bit of set dressing, the youth uactions went off without a hitch.

Several

Lewton regulars also appear. One is Elizabeth Russell, who briefly appeared as

the cat woman in Cat People and as the sickly neighbor in The Seventh Victim. Here

she’s Barbara, the witchy younger Farren. There’s also I Walked With A Zombie‘s

awesomely named Sir Lancelot as Oliver and Alice’s in-home help.

At it’s

best, story feels like Daniel Clowes’ Eightball.

Amy is a normal, fairly bright girl adrift in a world that makes a sense in a

way only she can see. Her parents’ wishes never seem rational, and presences

like Barbara move as if controlled by laws that belong to another plane.

There are

great little flourishes I like, such as Mrs. Farren’s expression as Amy is

whisked away following the rendition of the headless horseman legend. Her face

twists from amusement to resentment in a second, and the shift says a lot more

than dialogue could.

Instead

of hiding a family drama inside a genre plot, Curse more obviously

drips melodrama. Strange notes like the relationship between Barbara and

her mother — Mrs. Farren believes her daughter dead and Barbara an imposter — seem opportunistic and weird for weird’s sake.

.jpg)

Deep in the shadows, Drew’s addictions plan rebirth.

The same

ground-floor psychology that colors some of Lewton’s other films is used as a

plot device here too, and it infects the entire structure of the film. Irena

as an image that unites Oliver and Amy? Mrs. Farrin and her daughter as the

image of Oliver’s family as it could be? Sort of. It sounds better on paper

than it is on film. The threads don’t come together, and Curse feels like a few

short stories awkwardly grafted into a single narrative.

On the

commentary, Greg Mank makes a good case for Curse as Lewton’s most

explicit airing of his own problems. However resonant the movie might

be for Lewton and family, for outsiders it’s too obvious, cluttered and

unwieldy. Curse is an interesting film, featuring a great child

performance, but it will never compare to Lewton’s best.

Cat People: 9.6 out of 10

Curse of the Cat People: 6.5 out

of 10

The Look

Good

enough. I’ve still got tapes I backed up from the laserdisc box set in the mid

’90s, and while these discs look good, they’re basically the same presentation as those old discs. The Cat People print shows age in all the usual ways — blemishes,

scratches and a tiny jump every once in a while. The sequel is better, probably

because it’s not been touched as often. But the black is deep, the contrast is

good and the edges are no more sharp than they should be.

8 out of 10

The Noise

Warm and dewy, mostly. Almost music to my ears — if only it was a mastered a little better and with less legacy analog hiss. Roy Webb’s music is lush and sweeping when it should

be, demure and pensive when Lewton demands. Dialogue is natural and clear.

These aren’t audio stunners, but when the soundtrack drops to ambient sound

during key moments of Cat People, there’s still some analog hiss to distract from the minimal sound design.

7 out of 10

The Goodies

"Is

she frigid? Is she a lesbian? Is she a frigid lesbian? Or is she truly a cat

woman?" Greg Mank provides the commentary for both films. Both tracks are

of the composed, academic variety, but Mank’s voice is easy going and

conversational, so the tracks aren’t dry. Actually, they’re a lot of fun, as

you can tell from the quote. He’s exhaustively researched Lewton’s work, and

provides lots of detail on the origin, creation and reception of both movies.

For Curse,

he makes a great argument for the film as a dual-layer biography, with Oliver

and daughter Amy both standing in for Lewton at different points in life. It’s

probably spot-on, but my own reading and enjoyment of the film wasn’t much

improved by the background. After listening to the commentary I definitely see Curse

as a more interesting and relevant film, at least as far as Lewton’s

career goes, but I don’t have any greater desire to watch it again.

I’m wearing you.

I do

enjoy Mank’s constand name-dropping of other classic horror films. The way he

talks about them in context with Lewton’s movies makes me hungry to track down

the obscurities that we’ve mostly forgotten.

Both

tracks also feature some cut-in interview recordings with Simone Simon. They’re

more color commentary than anything else, but I did appreciate hearing from one

of the first-hand participants, especially years after her death.

8 out of 10

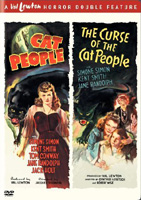

The Artwork

It’s

tough to add class to the cover of a double-feature disc, but Warners has done

a good job. The white frame is surprisingly good for the poster art for each

film, which appears in great color and detail despite the narrow space allotted

for each image. And though the films are ostensibly horror, the white frame is a good way to emphasize the fact that neither picture is in any way a typical horror flick. Given the options, this works nicely.

7 out of 10

Overall: 9.5 out of 10