Sometimes you get to a breaking point and you just have to say “enough is enough.” This week’s theme grew naturally out of a handful of movies that I saw in theaters that all seemed to resonate with that notion of hitting a limit and doing something about it. There are some great “enough is enough” movies out there–films that take that premise in revolutionary, visionary, destructive, or self-destructive directions. Here are the ones I watched for this column.

The Films

Hobo with a Shotgun (2011) dir. Jason Eisener

Hesher (2010) dir. Spencer Susser

Battleship Potemkin (1925) dir. Sergei Eisenstein

Billy Jack (1971) dir. Tom Laughlin

Wristcutters: A Love Story (2006) dir. Goran Dukic

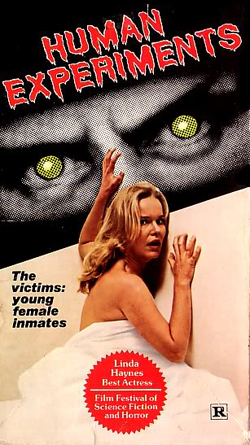

Human Experiments (1980) dir. Gregory Godell

Network (1976) dir. Sidney Lumet

Fight for What’s Right

In Hobo with a Shotgun Rutger Hauer plays a weathered, train-hopping bum who just wants to collect enough coins in his sock to buy a lawn mower. What he plans to mow in the urban wasteland where he ends up isn’t quite clear, but at least he has a goal. Too bad his pursuit of that goal is blocked at every turn by drug dealers, pimps, thugs, and hooligans who are fueled by chaos. When Hauer’s hobo is pushed to the breaking point, he does what we’d all like to do and becomes a Hobo with a Shotgun. With shotgun in hand and an endless supply of shells, he’s the Punisher with a few too many layers of clothes and a drinking problem. If you’ve seen the trailer, you know what you are getting yourself into. Hell, if you can’t tell what you are getting into from the title, you don’t watch enough movies. When Hauer has to face off with the crime lord’s secret weapons, a pair of hired guns called “The Plague,” the movie goes from fun to wonderfully absurd.

By stark contrast (in terms of film quality, anyway,) the crew of the Battleship Potemkin is fed up with rotten meat and substandard working conditions. Revolution is in the air, and they use that spirit to stand up to the officers who would kill them simply for complaining about borscht. Sergei Eisenstein’s film is an important piece of cinema history and I was lucky enough to see it on a big screen, accompanied by a live musical score by Graham Reynolds (A Scanner Darkly.) The film was fantastic and a great example of why people shouldn’t be so afraid of seeing silent movies. Without so much tedious dialog, the story unfolded from the images quite beautifully. Reynolds’ score was tense and menacing. The whole thing was a bit like seeing Godspeed You Black Emperor! play without any guitars, and with a narrative film instead of 16mm loops. It was incredible.

Fight for Yourself

Hesher is an audacious film that goes much deeper than its fun-filled trailer would suggest. Sure, it’s the story of a burnout metalhead who plows through a family in the midst of a crisis to some comedic affect, but it’s also a touching meditation on grief. The character of Hesher never seems quite real, which makes the whole film feel a little bit magical–especially when he is surrounded by people so out-of-it that they rarely flinch when he sets things on fire.

Hesher is brash, rude, violent, and a little bit crazed but he’s also full of his own strange kind of wisdom that he drops on people in the form of profanity-laden allegories. If these scenes felt like the screenwriter telling the audience how to feel, the film would have fallen apart, but Joseph Gordon-Levitt plays Hesher as a guy so on the edge that he may not even understand the meaning behind his own philosophy. Or if he does, he certainly doesn’t care if you do. Hesher is there to remind us that life keeps moving, so there’s no point in stopping to fucking cry about it.

Fight for a Better World

During the climactic standoff in Billy Jack, the girl that Billy has been protecting for the whole movie explains her motivation for staying by his side during a suicidal gunfight with the memorable observation that her “life has been one big shit brick.” She’s been pushed to the edge by an abusive father, manipulative men, and a town that would rather put Billy down and return her to her abuser than let her live in peace. The film never gives much detail about Billy’s past, but he seems motivated by a similar kind of cynicism, which is one of the things that makes the film so compelling.

Often our vigilantes are out for justice, or guided by some kind of desire to clean the world up. Billy Jack is more cynical and reactionary. He isn’t looking to build, but he doesn’t want the people who do bring light into the world messed with and he’s willing to step up to defend them when needed. In a weird way, Billy Jack knows what a better world would look like, but he doesn’t appear convinced that such a world is possible. He stands up for people and ideals when they are threatened, but by the end of the film, he’s still somewhat fatalistic about how much good he or anyone else can do.

Network is an absolute classic that is as riveting and appropriate today as it was in 1976. When news anchor Howard Beale goes off the deep end, the network’s immediate decision is to fire him and retool the news division into something more sensational. Through a brilliant twist of fate, they wind up using Beale and his doomsday prophet routine to front a new nightly news program that is one half The Price Is Right and one half 60 Minutes. What makes this work as a deep-cutting satire of the media is the absolute sincerity that goes into Beale’s tirades. He’s a cracked man, no doubt, but when he entreats his audience to open their windows and shout “I’m mad as hell and I’m not gonna take this anymore” he strikes a chord. There’s enough truth and insight in his madness to keep him from becoming a cartoon.

Network is one of the films that inspired this column, especially that famous scene where people join in the chant. As Beale thinks he is fighting the good fight and spreading his visions of the world to an open public, we get to see the machinations behind the scenes that turn everything into a deranged spectacle to edge out a few more ratings points. I don’t want to see Network remade in contemporary times with the current media landscape as a target–it doesn’t need one bit of an update–but I can see how this story might hit present-day audiences hard. Sometimes even when we fight, we are co-opted by the powers that be and turned into a commodity, a freakshow, or the very thing we are railing against.

Give In or Give Up

Not everyone who is pushed to the limit manages to come out swinging. Sometimes, as in these last films, characters hit that wall and simply give up. However, Wristcutters: A Love Story isn’t about the build up to that moment of ultimate decision. Instead, it’s a farce about the dull purgatory that awaits those who off themselves. Wristcutters is full of so much quirk that it sometimes falls victim to its own budget and goofy ideas. There’s a recurring gag about a vortex under the passenger seat of a car that would have worked so much better without Video Toaster quality CG effects, for instance. The film opens on a suicide, then flashes back to a lot more of them as it introduces the characters that inhabit purgatory. To be honest, I kept waiting for the “Love Story” portion of the movie to come into play, but something about being aimlessly lost in purgatory makes pursuing a love interest difficult. There are certainly better, more serious films about suicide out there, so if you are only looking for one–you might want not want this movie to be it.

In Human Experiments, a strong-willed female country singer is framed for a massacre and sent to prison. The movie gets all of that out of the way quickly so that it can move to the “women in prison” motif, but unlike more salacious prison exploitation movies, this one paints a strangely idyllic picture of life in the slammer. The women play ping pong, tend a garden, get treated to a funk concert, and even have a stand up video arcade game to play (that takes quarters!) There’s only one fight and it’s really just a push and a warning. The film doesn’t linger on nudity either, and an obligatory shower and examination scene is more creepy than titillating.

Human Experiments makes it in this week’s list because it’s about a sadistic (or maybe just misguided) psychiatrist whose idea of rehabilitation is a kind of psychological torture that breaks prisoners down to infancy so that they can be reborn as healthy individuals. It’s not quite the Ludovico Technique, but it runs closely parallel–and with the same warnings. In a sickly cynical turn, our heroine isn’t able to beat the drugs and mind games, so she is forced to acquiesce. For a movie that might have been promoted as a sensational piece of prison exploitation, it turned out to be quite a bit more psychologically disturbing than graphically shocking.

Other Movie Weeks in 2011:

Food Week

Divorce Week

ActionFest Week

Beat Takeshi Week

Atlanta Week

French Action Week

Childhood Fascination Week

Australian Rules Week

Black History Week

Vampire Week

Recent Westerns Week

Non-Godzilla Kaiju Week

Woody Allen Week

Secret Agent Week

Asian Action Week