Syriana is like the coolest social studies class you ever had. It’s fascinating, and it feels completely real and true, but in the end it’s also a touch academic.

Syriana is like the coolest social studies class you ever had. It’s fascinating, and it feels completely real and true, but in the end it’s also a touch academic.

Stephen Gaghan won an Academy Award for his script to Traffic, so it’s no surprise that Syriana feels in many ways like Traffic 2: What Else We’re Addicted To. It’s a fractured narrative that sprawls across the globe with pieces just sort of touching each other but never fully fitting together. In the end the parts that are left out aren’t story elements – I never found the movie as hard to follow as all the buzz would have you believe, you just have to pay attention – but rather an emotional core. Syriana is the rare long movie that I wish was just a little longer, so we could have more time to flesh out some of the characters.

The film is a triumph in many other ways – Gaghan does the almost impossible and pulls back his camera to illuminate the spider web that connects oil to the government to the politics of the Middle East to terrorism, and he deftly shows how tapping on one strand can cause every fiber to shake. It’s also a beautifully shot film; Gaghan shows that he has grown immeasurably as a filmmaker since his schlocky debut, Abandon.

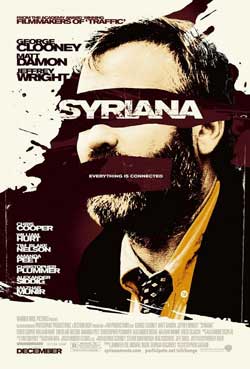

He’s got a lot of support from an astonishing cast as well. George Clooney shatters every expectation here, reminding us that he’s not just a great movie star but a damn fine actor as well. He’s a burnt-out CIA agent caught up in the political vagaries of the modern age, a veteran of a covert world that has now, more than ever, become disengaged from morality and meaning. The brouhaha is that Clooney gained weight and bearded up for the role, but I don’t think he needed to – he plays most of the character through his hollow eyes.

Working on another tangent, Matt Damon is a bright young ambitious energy analyst who parlays a personal tragedy into an advisory role to a radically progressive prince (Alexander Siddig, demolishing the Star Trek curse and proving that just because a guy once wore a unitard doesn’t mean he can’t bring the acting). The prince wants to expand his nation’s economy, removing its reliance on American oil dollars, and creating a more democratic state. This, it turns out, isn’t to the best interests of the Americans.

In another aspect of the story Jeffrey Wright is marvelous as a lawyer investigating a merger of two major energy companies. There’s plenty of underhanded dealings going on, and Wright has to find them before the feds do – and figure out who to sacrifice to make sure the merger can happen. But even while the feds are investigating the energy company, they’re also doing their bidding in the Middle East.

The final major storyline follows two Pakistani boys working at a refinery in the prince’s unnamed country. They find that the only people who treat them with respect are the imams at the local madrass, who also happen to teach a radical and violent interpretation of the Koran. Before long they are being molded into suicide bombers by a man who bought his weapons from the United States.

Gaghan does a masterful job of weaving these stories together. Again, many people will tell you that the film is hard to follow, but they’re completely wrong. It’s just a movie that demands your attention. Moviegoers aren’t used to that anymore, and it’s refreshing to sit down and spend the film’s two hour running time fully engaged in what’s going on onscreen because Gaghan isn’t interested in holding your hand through it all.

He makes paying attention easy not just because his frame is always fascinating to look at but because his dialogue pops. There’s plenty of jargon getting tossed around, but he trusts his actors to speak it like poetry.

It does sound like poetry, but it’s usually in the service of the academic. Gaghan doesn’t neglect the emotional aspects of his story, it’s just that that stuff comes off as fascinating rather than effecting. George Clooney’s spy must lie to his son; Jeffrey Wright’s old, alkie dad is unhappy with his son working for the Establishment; Matt Damon’s personal life falls apart after his tragedy. All of these plotlines feel like they’re truncated from longer films. Gaghan’s good enough that any of these stories could be a feature film unto itself; unfortunately he leaves us kind of wishing they were.

The story with the most immediate emotional impact is the journey of the suicide bombers. I would say that it’s an unusually sympathetic portrait of what drives young men into the madness of terrorism, but it’s ground that’s been covered recently in great films like Paradise Now and TBS’ underseen miniseries The Grid. Even still, Gaghan handles the story with a kind of sympathy sure to infuriate right wingers intent on seeing the roots of terrorism only in evil.

Syriana is a film that will probably infuriate right wingers in general, which is just silly. The movie has been described as left wing, but to me it’s even more neutral than Sam Mendes’ Jarhead – this is what is happening. This is what is happening in the Middle East and this is what is happening in the corridors of American power and this is what is happening in the boardrooms of multinational energy companies every single day. It’s like Traffic in that way – you can’t attack a film for reflecting reality.

I am tempted to attack the film for pulling its punches, though. The movie posits the problems of oil and terrorism as a cycle, with every element feeding into every other element. Which is true enough. But there are elements that, in the real world, are more responsible than others, and they need to be named. It’s frustrating to watch this film taking place in an alternate universe where Saudi Arabia isn’t named, where George Bush isn’t called out, where Dick Cheney’s potentially illegal collusion with energy companies is ignored. Gaghan fills his movie with enough fact and reality to give it the sheen of reality – I wish it had gone further in that direction. In the post-Watergate world of entertainment we’re used to the bad guys being vague government and big business types.

Syriana is a dense, layered film that is essentially this season’s broccoli – it’s good for you, and when prepared right (as Gaghan has), tasty. In the end Gaghan doesn’t quite capture the emotional wallop that he did with Traffic, but it doesn’t necessarily make Syriana a lesser film. There’s still plenty to chew on here, and even more to enjoy.