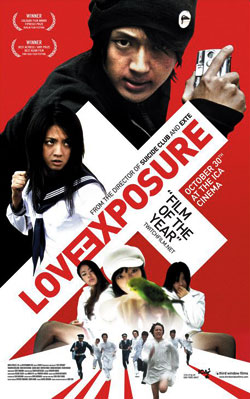

There are two important things for you to know up front about Love Exposure, avant-garde poet and Suicide Circle director Sion Sono’s 2008 Japanese urban-epic, which is receiving a shamefully limited theatrical release in America. Those two things are:

There are two important things for you to know up front about Love Exposure, avant-garde poet and Suicide Circle director Sion Sono’s 2008 Japanese urban-epic, which is receiving a shamefully limited theatrical release in America. Those two things are:

1) it is 4 hours long.

2) it is an extraordinary singular experience.

This could easily be viewed as a Bad News/Good News trade-off, I suppose. There is no denying that, generally speaking, the idea of sitting down for a 4-hour movie seems perfectly awful. But it is the sheer expanse of Sono’s mesmerizingly eccentric opus that is the key to its singularity. A 120-minute Love Exposure, featuring the choicest highlights and performances, would likely have been an entertaining and interesting film, but given the freedom to breath and do its mad thing at its own pace, something really special happens here. I said “extraordinary experience” instead of “extraordinary film” because Love Exposure is one of those rare movies that I’d recommend to anyone with a serious interest in cinema even if I didn’t necessarily think they’d like its content. It’s just one of those movies you need to see. And I don’t mean that like “You need to see The Cove, man, so you know what’s happening to the dolphins!” but rather that you need to see it for you. This is one everyone will want to talk about. And it will haunt your mind for weeks, if not months. Love Exposure is the first great film I’ve seen in 2011.

The elephant in the room with Love Exposure is of course its run time: 237 minutes. Talking someone – myself included – into watching anything over 2 1/2 hours long is tough to do even when orcs are involved, but Love Exposure does not play like a 4-hour movie. This is because it doesn’t really play like a movie at all. Watching Love Exposure doesn’t feel like watching Lawrence of Arabia or the extended edition of Return of the King, but rather like burning through an entire TV mini-series on DVD in one sitting. Not entirely unlike Kill Bill, Love Exposure has mini-arcs and major tone shifts that keep the energy fresh and high, but to an extent that makes Tarantino’s film seem conventionally focused and reserved. Love Exposure almost feels like the work of a dying man making his first and last film, and cramming every technique and genre he’d dreamed of tackling one day into a single bucket list supermovie. Part teen comedy, part family drama, part martial arts spectacular, part splatter horror movie, part rom-com farce, part romantic melodrama, part fetish film, part religious exploration, part satire, part surrealist art film, part disturbing thriller — Love Exposure is what we might have gotten if Alejandro Jodorowsky had been Japanese and into up-skirt photography (is that redundant?).

Trying to describe the film’s story is a tall order, but here goes…

Our central character is Yu Honda (Japanese pop star, Takahiro Nishijima). As a child Yu was raised by a devoutly Japanese-Catholic mother, and before she dies tragically from illness she gives lil’ Yu a ceramic Mary (mother of that Jesus guy) figurine and tells Yu that one day he will meet a perfect girl, like Mary. This is the heart of the film. The prologue ends with Yu’s father, Tetsu (Atsuro Watabe), deeply moved by the death of his wife, becoming a Catholic priest. In the present, Yu is now in high school, bright-eyed and cheery, and Tetsu is a wonderful priest — that is until he meets the wild and passionate Kaori (Makiko Watanabe), whose fiery feelings for Tetsu are too strong for the man to resist (at one point when Tetsu tries to flee, Kaori drives his car off the road and into a lake, nearly killing him, and then tries to jump his bones in the water as if nothing had happened). They begin an affair, but priests aren’t allowed to marry, so Kaori leaves as suddenly as she burst into town. Tetsu now becomes a despondent and mean-spirited preacher. He demands that Yu confess his sins everyday, but Yu never sins. In Yu’s silly mind he decides he needs to start sinning so he has things to confess. He joins the bad crowd at school, and soon finds himself the apprentice to an up-skirt fetish photographer who uses wire-fu style martial arts to capture pictures of unsuspecting girls’ panties. Yes, you read that right. Up-skirt photography martial arts. Soon Yu is a master of up-skirt-fu and has disciples of his own, but his life changes forever – for better and worse – when he meets two different girls. One, Yoko (Hikari Mitsushima), is a plucky young girl who decided a long time ago that she hates boys. Yu falls immediately in love with her. Thank god he happens to be dressed as a woman when he jumps into a street rumble to fight by her side. Two, Aya Koike (Sakura Ando), another young lady who lurks in the shadows toying with her pet bird, and seems to have a sinister interest in Yu and his family. She also seems affiliated with a massive and well-organized cult that is all over the headlines.

And that’s just Act I! I barely scratched the surface. There are like four movies’ worth of storylines left that I didn’t touch on. And as nutty as elements in that description sound, the film ends up getting so much weirder and wilder and darker, going places I was never able to predict or even imagine.

The film has fantastic performances all around, but the wealth of praise needs to go to Takahiro Nishijima as Yu. It feels weird calling another man adorable, but I can’t think of a better way to describe the performance of Yu in the first chapter of the film (this film defies three-act structure; chapter feels more accurate). The naive dumbass smile plastered on his face as he delves into the life of a sinner is utterly endearing, roping you into his nonsensical logic all to the jaunty tune of Yu’s theme song, Maurice Ravel’s Bolero. That smile will eventually become a painful and distant echo as the film sinks to darker and more brutal depths. This is an area in which the film’s massive length does something a 90-minute movie simply can’t do in the same way. Again, it is more akin to TV, for we live with cheerful, up-beat Yu for well over the length of a regular motion picture, before he is slowly crushed by relentlessly cruel circumstances. The sheer duration of the silly good times makes the unstinting lows that eventually come seem all the more intense and emotional.

Yet, this isn’t Audition. This isn’t a light comedy that flips into a horrifying thriller. Love Exposure switches up what kind of film we’re watching probably around six or seven times, if not more, depending on how rigidly one would categorize it. Slapping together a bloated genre-shifting film doesn’t seem like too tall an order if you have the time and money to waste, and aren’t concerned with producing something watchable. What’s insane about Love Exposure is that Sono had only a few weeks to shoot the entire goddamn thing (and the rough cut was six hours long!), and the film feels like a masterwork. The genre shifts are completely seamless. I don’t want to give the impression that we’re watching a high school comedy and then suddenly the cinematography changes and we’re in a horror movie that feels completely alien from what we’ve just been seeing. Sono takes us fluidly from chapter to chapter; it never actually feels like we’ve left the position we’d just been in. I don’t want to call the film “dreamlike,” because that implies a slow pace, but the way it morphs effortlessly from screwball comedy to fierce drama to dopey romance to butt-clenching tension back to screwball comedy again feels not unlike a dream or nightmare.

There are so many facets to this movie that can be discussed it is actually a bit overwhelming, from a critical perspective. As much story as there is, I don’t want to give anything more away; the crazy unraveling of the story is part of the epic journey. Though it should be said that the movie is extremely funny — at times in a silly G-rated way and at others in a pitch-black way; this is the guy who created the subway gore-splosion opening sequence to Suicide Circle (or Suicide Club) after all. So you get the silliness of a classic martial arts training montage, with Yu practicing taking pictures of crotches, mixed in with twisted geysers of gore and dismemberment. Part of the film’s strength, and the surprising breeziness of its 4-hour length, is that even when the film gets serious, it almost never completely does away with the humor. And that makes the handful of moments with truly zero humor to them feel almost like body blows. You just don’t see shit coming. Sono can turn on a dime.

It is somewhat amazing that Love Exposure came from a 50-year-old man. It is so youthful and vibrant, and frankly the zenith of the kind of modern frenetic and debased cinema that older curmudgeons so often hate. Simply reading the backstory to the film – Sono’s impossibly short shooting schedule, his script that was hundreds of pages long, his battles with the producers to keep the film’s insane length – sounds like the makings of a film that is noteworthy only for what a fascinating mess it is (Southland Tales anyone?). The level of solidified vision Sono must have had to execute this film in just over 20 days is crystallized mad genius. It boggles the mind. Because the movie isn’t long due to long scenes of endless dialogue. To the contrary, it feels like Sono is in a race, blasting through scenes and plotpoints with a frantic speed. Love Exposure cooks and rarely lets up. For 4 hours.

Saying “if you only see one movie this year, it should be Love Exposure” would be cheating, because watching Love Exposure is more like watching an entire trilogy. The film’s title ties into a line spoken by Yoko, who says that she enjoys the wild Kaori’s company because Kaori seems so “exposed” — to the world, to love. All our central characters suffer from love exposure, in the same way someone trapped in the desert might suffer from sun exposure. And when the credits finally roll, you will feel as if you’re suffering from Love Exposure exposure.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars