Chris Columbus’ film adaptation of Rent begins perfectly, with the cast lined up on a dark stage, singing the show’s signature number, Seasons of Love. The song has been moved from its spot on stage, and here it creates an ideal portal through which to enter the story.

Chris Columbus’ film adaptation of Rent begins perfectly, with the cast lined up on a dark stage, singing the show’s signature number, Seasons of Love. The song has been moved from its spot on stage, and here it creates an ideal portal through which to enter the story.

It’s also the most stylized moment of the film. Columbus has opted to plant his musical in something approaching reality, which means that we’re not going to get huge musical numbers and dance routines. On some levels I can understand why that would be – Rent is a street-level story, and modern audiences will probably have a hard enough time dealing with people bursting into song. But the decision also robs the film of a certain level of vitality, and often renders it sluggish.

Weirdly, he begins with a big number, the only one in the film. It’s the title song, and it ends with everyone on our heroes’ block coming out of their windows and lighting their eviction notices on fire. It’s a great moment, and it’s exhilarating, but it’s all by itself. More numbers like Rent would have vaulted this film over the top, but even with Columbus’ logy direction, the inherent power of the songs propels you along. Add to that cast members who throw themselves soul-first into their roles and Rent becomes more than the sum of its parts – but still not the movie it could be.

The story is the same as the show, but perhaps a little clearer, narratively speaking. It’s the last days of 1989, and two friends, Mark, a filmmaker, and Roger, a musician with AIDS, are best friends and roommates in a loft in New York City’s Alphabet City whose rent has been unpaid for a year. On Christmas Eve they discover that their old roommate Benny, who married the landlord’s daughter is going to evict them, and close down a performance space in a nearby empty lot to make way for a “cyberstudio.” Meanwhile, old friend and radical professor Tom Collins shows up for the holidays, and meets local crossdressing humanitarian Angel. They fall in love and discover that they’re both living with AIDS. Downstairs from Mark and Roger lives Mimi, an exotic dancer and drug addict who takes a shine to Roger, who has been depressed since he contracted AIDS. And to round it all off, Mark’s ex-girlfriend Maureen is a performance artist who is staging a protest at the empty lot with the help of her new lover, a lawyer named Joanne.

Phew. And that’s just where things start – the story spans a year of their lives, as characters fall in love and die. No wonder some playbills for the show had to include a chart to help you keep track of relationships.

One of the concerns I had going in was that the story would feel too dated. While the show was written at the height of AIDS awareness in the United States, the thematic elements of Rent are timeless – Roger’s One Song Glory is the cry of any artist aware of his mortality. Here it just happens to be AIDS-specific. Of course the fact that just about everyone in the play has AIDS feels a little dated, but I think the issue isn’t really the time period – even when I first heard the Rent soundtrack in 1997, the sheer amount of infection among the characters seemed excessive. Team America’s parody remains on the nose.

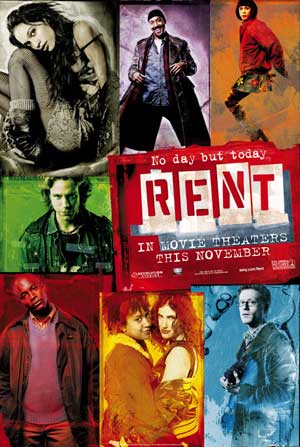

Two of the best performances come from the newcomers. Six of the eight leads originated their roles in the Broadway production ten years ago, but Tracie Thomas as Joanne and Rosario Dawson as Mimi are new, and they bring a freshness and vibrancy to their roles. Dawson’s a huge surprise – we knew she could be sexy as hell and act, but she can also really sing. Her performance of Out Tonight is feral – she’s hungry like the wolf. Too bad that Columbus doesn’t let the frame open up to give her room to really explode.

I’ve always had a problem with Anthony Rapp’s voice. It’s too whiny. But I had never seen the show, so I wasn’t aware of his presence, which fits perfectly with Mark the nebbishy wanna-be hipster. Wilson Jermaine Heredia won a Tony for his turn as Angel, but I have to say that I don’t feel him here. He’s not bad, and his big number, Today 4 U, is fantastic (although again, constrained by direction), but I felt Angel to be a poorly sketched character. Tom Collins, however, is a blast. Law & Order’s Jesse L Martin plays him as a rowdy, almost lecherous man. The original cast is, arguably too old for their roles in this film, but Collins works as a guy in his 30s (and Rapp is pretty convincing playing younger. Other cast members seem like they’re playing people who should have grown up and gotten real jobs already).

The weakest pieces are Adam Pascal as Roger, looking so distractingly like Kinickie from Grease that it only compounded his dull acting. Idina Menzel, lately a star of Wicked, is stuck with Maureen, a character I found so unlikable that I wanted to hit the bathroom during her big dumb performance art song. Menzel is the most Broadway feeling of the cast, and she’s just too broad. I know that that’s an aspect of Maureen’s diva personality, but it’s still irritating. Finally Taye Diggs is fine as Benny, but the poor guy gets nothing to do the whole film. He drifts in and out of the narrative at random, it seems.

The narrative is a little bit of a problem on the big screen in general. The film feels like it climaxes with La Vie Boheme, a rousing and wonderful song that hearkens back to Hair in many ways – but it’s just the midpoint of the film. From that point on, though, I couldn’t help but feel like Columbus had shot Rent 2 and tacked it onto the end of the real film. A show is structured differently from a film, with an intermission planned in the middle. I don’t know how that structural issue could be overcome on the screen, but it only compounds the lethargy of Columbus’ style.

It’s not that Columbus is egregiously bad here. Rent reminds me of the first Harry Potter in many ways, in that it’s directed modestly well but without any flair or personality. Again, Larson’s songs can’t be defeated (I feel no shame in admitting that the “No day but today” refrain still chokes me up years after first hearing it. Sometimes it’s the simplest things said in the simplest ways that ring truest), but Columbus isn’t working with them. He wants to ground the film in reality but shoots much of it on a fakey looking set, since the real Lower East Side has gentrified too much to stand in for the decrepit slums of just 15 years ago. Dawson electrifies with Out Tonight, but the sight of her stalking down the empty, boring streets of this set in no way adds to the number. This scene is a microcosm of the whole film: Columbus should have knocked this one out of the park, but settles for a double.