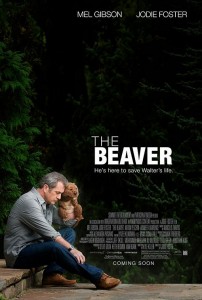

The Beaver is the kind of film that lives or dies in Act III. And unfortunately Jodie Foster’s new dark dramedy dies. Which is too bad, because the first half of the film is kind of great.

The Beaver is the kind of film that lives or dies in Act III. And unfortunately Jodie Foster’s new dark dramedy dies. Which is too bad, because the first half of the film is kind of great.

Walter Black (Mel Gibson) is being crushed under the weight of severe depression. He has the pieces for a good life, but it has all turned to shit: he inherited his father’s toy company and promptly ran it into the ground, and his relationships with his wife Meredith (Foster) and his oldest son Porter (Anton Yelchin) have been run into the ground too. When Meredith kicks Walter out, he does the next logical thing — he gets shitfaced and tries to kill himself in a hotel room. Only he can’t do that right either. After knocking himself unconscious, Walter awakes to find he has a new friend and mentor: the Beaver, a shitty hand-puppet Walter had nabbed from home while moving out. But it’s just Walter talking to himself. He has been mentally cleaved in two. With the Beaver taking charge and doing all the talking, Walter has a filter through which he can tackle life with a fresh perspective. He starts kicking ass at work, and starts winning back his family. This A-Plot is intertwined with a B-Plot about Porter, whose entire goal in life is to make sure he doesn’t turn out like Walter. Porter makes money writing papers for his fellow students, and has developed a rep for his amazing ability to mimic the writing-voice of his clients. This causes the valedictorian, Norah (Winter’s Bone‘s Jennifer Lawrence), to hire Porter to write her graduation speech. A relationship develops. For a while everything seems to be going aces for everyone, until it becomes clear that Walter isn’t just being silly – he’s seriously fucking crazy.

The elephant in the room with The Beaver is of course Mel Gibson’s much publicized personal life. So we might as well address this first. For me the Gibson “scandal” was incredibly disappointing. While many people seem pushed to extremes on the subject, either painting Gibson as a terrible monster deserving of great retribution, or casually dismissing the whole thing with idiotic and revealing statements like, “Oh, whatever, like none of us have said racist things when we’re drunk and angry,” I am as I said — disappointed. This is a review of a movie, not an editorial on Gibson or America’s relationship with celebrities, so I won’t delve any deeper than to say that I was disappointed in Gibson for being such a fuck up that he altered the ambiguous image I had of him in my mind, which actors need to successfully do their job. It is a little disturbing how easy it is to overlook racism or sexism or domestic violence or other disgusting personality traits in our artists and athletes. But the moat of detachment between us and them makes it not only possible, but pretty easy. After all, these bad things are just words we read on gossip blogs or in magazines. But Gibson’s numerous recorded drunken psycho rants were a little different. Ignoring my own personal feelings on racism and sexism, the most damaging thing Gibson did for me as a viewer of his material was making me think he’s pathetic. Sounds silly to say, but when I’ve tried to rewatch favorite Gibson films of yore, that is what is getting in my way. I’m not thinking, “Oh, that dude hates Jews.” Gibson destroyed the veil between him and me. Now I look into his eyes and see the sad, sad man trapped inside. He just can’t fool me anymore.

So, oddly enough, I thought Gibson’s media black eye actually added to my immersion in The Beaver. At least at the beginning. Whether it was simply reality, or my new perception of the man, I don’t know. But Gibson looks like shit here. Not like “movie shit,” but genuine shit. He seems shorter than I remember. He’s paunchier than he’s ever been. His once luxurious brown mane of hair is now a gray nest of pubes. He’s aged so quickly in the past couple years you’d think he were the President. The set-up for Walter’s depression is incredibly ungrounded in the script. In American Beauty fashion, a voice over simply tells us that Walter is depressed and crushed by the world. Normally I might have an issue with this. Why is Walter so depressed? We aren’t told. He just is. Presumably weltschmerz (only the Germans would have a single word for that). But I bought it, fully, because staring into Gibson’s haggard face and perpetually wet eyes I saw deep sadness. It is frankly kind of shocking that this was something he shot before his scandal broke, because the parallels between Walter trying to change his family’s impressions of him via a puppet has pretty obvious metaphorical echos with an actor trying to change the public’s view of him with a movie. As it is, it is just a convenient coincidence.

Bottom line is – racism, sexism, alcoholism, alleged shitty wife facing punching aside – Gibson is fantastic in the film. After suffering through Edge of Darkness I had thought that maybe Gibson was over, that his life had poisoned his ability to put on masks for us, but as far as channeling pure talent, Gibson has really never been better than he is in The Beaver. The wide-eyed charm of Walter’s desperation to be a new and better man is contagious, as Gibson’s charm always has been. And if nothing else, The Beaver demonstrates that Gibson should be doing a lot more voice work. The dude has got some serious skillz. The very concept of this movie rests on our ability to tolerate a man talking through a puppet 80% of the time. And Gibson’s Beaver voice is great and hilarious — a deep, surly and “mate”-laden Australian snarl. The scenes of the Beaver putting Walter’s life back together are where the movie really sings. Jodie Foster’s character exists mostly to react to Gibson, but Meredith’s yearning to reclaim her once happy marriage is both cute and sad as she fully accepts the Beaver’s presence, even during passionate love-making sessions and post-coital snuggling. And Walter relationship with his youngest son (Riley Thomas Stewart) is pretty adorable. The real sadness that Gibson can no longer hide from me in his eyes ruined the movie-illusion in some of the film’s final moments, but by that point Gibson’s performance can’t save the film’s many problems and missteps anyway. So it doesn’t matter.

I have to give screenwriter Kyle Killen props for writing a ballsy movie. And further props to those who greenlit The Beaver for keeping it that way. The concept easily could have been re-written as a big dumb Jim Carrey family comedy. Pretty Woman began life as a dark drama, but everyone saw the rom-com dollar signs beneath the surface. The Beaver goes to some fucked up places; one particular plot point I didn’t see coming. Though, objectively speaking, it probably should’ve been turned into a dumb Jim Carrey movie. While this darker version was surely significantly more interesting, it ultimately started to feel like Killen was struggling to make the film darker than its concept could go; or at least than Killen could go. I can’t really discuss the problems with the final third of the film or its resolution without spoilers, but well before Act III there is a scene midway through The Beaver when it suddenly trips and never regains its balance. Walter and Meredith are dining at a fancy restaurant for their anniversary and Meredith demands that Walter stop speaking through the Beaver. He tries, but ends up completely falling apart. The scene isn’t played for laughs. It is very serious. But is just doesn’t quite work. I don’t think the problem is that the ideas of Walter and the Beaver are too silly to be taken seriously, but rather that Killen just doesn’t have a tight grasp on what he’s dealing with.

The movie is all about depression. Walter is depressed. Porter doesn’t want to be like Walter, and this is making him depressed. Porter’s subplot with Norah takes shape as Porter begins discovering dark tortured secrets beneath the exterior of this seemingly bland and perfect cheerleader overachiever, who herself is crippling depressed inside. And when all these issues remain at the surface the film sails smoothly. But in that dinner scene, when Walter breaks down and starts speechifying about depression, we realize the extent of Walter’s craziness and things start to get choppy. Then it just gets worse. Walter becomes famous after the media learns that the head of this toy company talks with a puppet at all times. He goes on TV and gives a fairly hollow and illogical speech about depression, and this makes him a big star. All of this could have worked in a Jim Carry family film, but The Beaver is asking to be taken seriously and it just doesn’t go deep enough for that. The farther and father it moves away from its silly puppet concept, the artistically weaker and the less enjoyable the film gets. It just stops being good enough, and becomes overly “indie.”

In the 90’s, “indie film,” like “alternative music,” went from a literal classification to describing more of a genre or subgenre, full of its own conventions and tropes. I don’t really like “indie” films. The Porter and Norah subplot is the most indie thing about The Beaver, full of twee deepness and artificial-feeling human moments. I think I could have stomached the deficiencies with Walter’s storyline if we hadn’t had the Porter-Norah subplot at all. As is, the movie just bit off more seriousness than it could chew. I’m also not a big Yelchin fan. I have no particular dislike for guy, and I think he’s a good actor, but there is something kind of robotic and off-putting about him that never makes me happy to see him in a film where he’s just playing some regular kid. Someone needs to cast Yelchin as a creepy murderer, pronto. Jennifer Lawrence is great though, and she is what manages to save this overly indie story thread for the majority of the film. Though it lands with a thud at the end, just like Walter’s story. It is tempting to say that Killen just doesn’t understand depression, but I don’t claim to understand it fully myself either. Whatever the root of the problem is, The Beaver is far too entrenched in the fallout of depression for how uninspiredly it deals with the subject. I don’t think Killen was trying to be profound with his script, but it definitely suffers from positioning itself like it has something real to say — which then exposes a void when you realize it doesn’t.

All-in-all, I’d say the film is worth seeing. But definitely a rental. Unless you’re just jonesing for some quality Gibson immediately. And if that’s what you’re after, you won’t be disappointed. Gibson kills, even if the movie itself flounders.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars