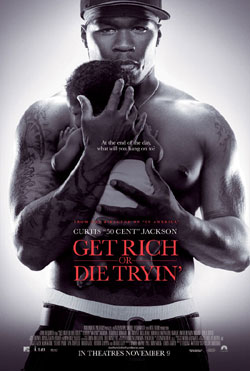

Jim Sheridan’s new film, Get Rich or Die Tryin’ has one huge, obvious flaw, and it’s fatal. His star, 50 Cent, aka Curtis Jackson, is painfully bad at acting. This is especially tragic as 50 is playing a character who is based completely on him, and whose life is based on his own. 50’s performance is the filmic equivalent of the Adam Carolla show, where you watch with ever growing horror at the disaster in front of you.

Jim Sheridan’s new film, Get Rich or Die Tryin’ has one huge, obvious flaw, and it’s fatal. His star, 50 Cent, aka Curtis Jackson, is painfully bad at acting. This is especially tragic as 50 is playing a character who is based completely on him, and whose life is based on his own. 50’s performance is the filmic equivalent of the Adam Carolla show, where you watch with ever growing horror at the disaster in front of you.

50 spends the film with one look on his face, and it’s the look that you imagine a caveman would have when confronted with a cellphone. Not only is this bad because we need to care about him (he is our protagonist), but because he’s the eye in a hurricane of much more talented actors. Not only does every line they deliver remind us that 50 is like a block of wood they’re acting against (one imagines the tennis balls on sticks used to denote eyelines for CGI monsters give more back to actors), but that they’re acting at all. The whole effect is to demolish suspension of disbelief, keeping us eternally at arm’s length from the film.

The film’s first mistake is introducing Terrence Howard at the beginning. Get Rich opens with a botched robbery, with Howard playing Bama, a crazy best friend in the best Joe Pesci/Johnny Boy from Mean Streets tradition. Howard sizzles – this film completes his great roles trifecta for 2005. Any one of these three great roles – Crash, Hustle & Flow and now Get Rich – could define his career, but the convergence of all of them will be the truly defining thing. And while Bama is a vital, hilarious and frightening character, Sheridan brings him in only to withhold him through much of the rest of the film’s running time.

You see, right after that botched robbery, the 50 Cent character (here known by the name Marcus, or the rap name Little Caesar (the sort of name that feels more like the invention of a screenwriter than a real street kid – how many urban toughs are watching gangster pictures from seventy years ago?)) is shot nine times, and most of the rest of the film becomes a long flashback to how he ended up riddled with bullets in the first place. That flashback stretches out, seemingly forever.

Marcus’ mom is a dope peddler, working for the ghetto kingpin’s right hand man, Mr. Majestic (but this isn’t Charles Bronson – it’s Oz’s Ababisi, Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, here almost accent-free – but no less menacing. He’s a wonderful dark spot on the movie’s heart, and another actor who reinforces how bad 50 is). When she gets killed, the young boy goes to live with his grandparents, who have eight other mouths to feed. Since they can’t keep him in the designer sneakers he wants, young Marcus starts pushing drugs himself.

Young Marcus grows into 50 Cent, still hustling around town. But now crack is invented (which really makes no sense. I don’t have a good grip on the exact timeline of this film, but going by 50’s own life, crack was on the streets when he was a little kid), and Marcus and his crew work hard and start making it big. Soon, though, someone from his past returns – the girl from across the way, who moved when she was 12. Now she’s a dancer, and improbably has absolutely no problem getting involved with a crack dealer.

That’s one of the film’s bigger logical lapses. Most of Get Rich follows a fairly trite gangster story, and every gangster who will survive the film must have a woman who is better than him, so she can pull him up later. But what does this woman see in this grunting thug? We surely never see it.

All of this business is leading Marcus to prison, and to the birth of a son. In prison he meets Bama (in a shower fight that Sheridan shoots with a strangely objective camera. Is this supposed to be as completely comic as it’s played? Given the nature of Bama’s later scenes, I think so, but at the time it was bizarre, as the film didn’t previously have much of a sense of humor) and decides to go straight – it’s going to be music he slings, not rock. Which is all fine and dandy except that you never buy that.

In 8 Mile, Eminem’s need to be making music was palpable. It was how he expressed himself and escaped himself. 50 isn’t expressing himself. His rhymes are slurred and cluttered, and I often found myself wondering if we were supposed to take the scenes of his nascent rapping to indicate that he was bad at it. If so, he certainly doesn’t get much better until the very end, when he performs live. Which seems miraculous.

There is one thing I liked about the fact that 50’s rapping doesn’t come across well – it makes the whole rap game seem to be about will, and not skill. If there’s one quality that 50 can get across on screen it is sheer pigheaded stubbornness. In this film he is the ultimate self-made man.

There’s not a surprising moment in Get Rich or Die Tryin’. That in and of itself isn’t the worst sin a movie can make – look at how many classic films telegraph every moment a mile away. But the presentation has to be something special, and this film can’t make anything special out of its lead actor. He deflates almost every scene he’s in, and his underplaying of every moment creates rifts between his energy and that of his co-stars, many of whom seem to think they’re in a flashy and mildly silly blaxploitation film. I would like to see that movie – Howard and Akinnuoye-Agbaje certainly present an intriguing trailer for it, as does Predator’s Bill Duke as the ghetto kingpin, ludicrously and wonderfully riffing on Brando in The Godfather.

And where is Jim Sheridan in all this? The movie has small moments that work nicely, but all too often it’s just another grind along the same old, same old path. Get Rich has none of the brutal honestly and careful complexity of his other films about difficult, troubled men – In the Name of the Father and My Left Foot. As the film careens to it’s overly obvious conclusion, we realize that what we have sat through is the two hour narrative version of the rapper’s usual retort to C Delores Tucker and friends: “We’re the black CNN, reporting what we see,” “If I wasn’t rapping about slinging rock and shooting people, I would actually be doing it,” etc etc etc. Those are valid points, but somewhere along the way the idea of actually dramatizing them as fully fleshed out ideas got lost in favor of an aggrandizing story of a man overcoming each and every single last obstacle on his way to starring in his own life story.