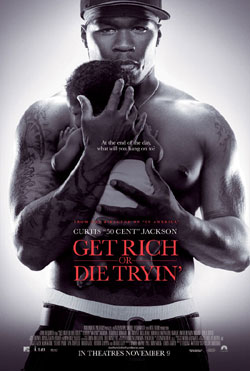

2005 has been an amazing year for Terence Howard, and he caps it off with a fantastic performance in the 50 Cent movie Get Rich or Die Tryin’. He plays Bama, a sociopath in the best Joe Pesci mode who 50’s character meets in a fight in a prison shower. Howard owns every scene he’s in, and he makes you wish he was in many more.

2005 has been an amazing year for Terence Howard, and he caps it off with a fantastic performance in the 50 Cent movie Get Rich or Die Tryin’. He plays Bama, a sociopath in the best Joe Pesci mode who 50’s character meets in a fight in a prison shower. Howard owns every scene he’s in, and he makes you wish he was in many more.

Last week the Essex House hotel on Central Park was the host of the press day for Get Rich or Die Tryin’, and Howard was there to talk about the film and his career. Last time I spoke to him, for Hustle & Flow, he seemed more guarded. This time he was open and joking. I think the difference was that last time the eye of all the media was focused right on him – here he doesn’t have to carry the movie, and it’s a supporting role and not his breakout lead.

Q: That shower scene – was that you running around naked?

Howard: No, that was a stand-in. I am much better endowed! Or it was a very cold day.

Q: How did you ease into that?

Howard: I didn’t ease into that. My friend Jim Sheridan was sitting there, struggling for two hours with a scene that he wanted. We tried to do it with coverings and all that and it was not a part of his vision. It was hurting him. I saw him sitting at the monitor just rubbing his head. I went to Jim and – I guess I should have been smarter and shouldn’t have done it.

I went to Jim and I said, ‘Can we do one more?’ He said, ‘I don’t know if it’s going to make a difference.’ I said, ‘You know what?’ I took my drawers off and I turned to 50 and I said, ‘This is us. This is who we are.’

He said, ‘Nigger, fuck you! I am not there. They ain’t gonna put a poster of you up. Me they gonna freeze frame and put a poster up and say, Look at 50’s bitch ass!’

I said, ‘Just try it. Jim really needs it.’ And he said, fuck it, took his drawers off, jumped right in. The other five people in the scene did it too, and then you saw Jim all excited again. He was all alive. I was happy.

Q: You’ve been around for a bunch of years –

Howard: Twenty years. This is the 20th year. Q: But it’s only been really this year that you’ve gotten noticed in a big way. What happened?

Q: But it’s only been really this year that you’ve gotten noticed in a big way. What happened?

Howard: The difference is that before I was warring against the entire world and wouldn’t surrender to the director. Kathy Bates told me in 1997 at the Sundance Lab, she said, ‘You’ve got to trust your director.’ It took six or seven years for that to sink in. I lent myself to that this year, and look at what a difference it’s made. I’ve stopped doing Terence Howard impersonations.

Q: Have you learned to trust your instinct?

Howard: You’ve got to surrender and trust the director’s instinct. Your instinct – ‘He who isolates himself will seek out his own selfish longing, and against all practical wisdom he will break forth.’ That was me before. When I learned to surrender to what they wanted, then I saw new characters created. But before they were all just reflections of me.

I couldn’t be used by a director for more than one scene because I was too difficult to deal with. I just thought these people were idiots, I thought they didn’t know what was going on. Jeffrey Wright had to sit me down and tell me I was my own worst enemy, because I refused to get out of my own way.

Q: So Crash was the first film you did that?

Howard: Paul Haggis just looked at me and said, ‘Terence, what I need you to bring to this movie, I can’t ask you to bring it because I don’t know what it is. But I’ll get it along the way – just trust me along the way. I promise you I will not lead you wrong, and if you never work again, you can come live in my house with me.’

Craig Brewer is like this with you: ‘I think you can do it. I think you can do it.’ He’s such a pimp. Honestly.

And Jim will say, ‘It’s a buncha crap. It doesn’t make sense, I can’t do it. What do you think? What do ya want to try?’

For him to ask me what do I want to try after having a year of learning to just surrender, I was like a little kid. He allowed you to bring your own base. You bring the clay and then he molded it into his city. But it was my clay that I brought and he let me play with it.

Q: How well do you know the world of this film?

Howard: As a young black male I grew up in the same environment. Fortunately for myself, I had my father who had a rule that we couldn’t play with anybody in the neighborhood. When we got from school, because he was at work – when he was home we could be in the front yard. But we had to stay inside the gate and none of our friends could come inside the gate and nobody could loiter. So people would come to the gate and talk to you for a minute over the gate and over the wall. When he was not home we had to be inside. And when the street lights came on, we had to be inside. We couldn’t be walking inside the house. And my father believed in corporal punishment, so we would get whupped. My father used to say, ‘You may hate me now, but I promise you’ll be alive to hate me when you’re 40.’

believed in corporal punishment, so we would get whupped. My father used to say, ‘You may hate me now, but I promise you’ll be alive to hate me when you’re 40.’

Q: And you agree with that now?

Howard: I raise my kids that way.

Q: Rap isn’t your kind of music. But has Hustle & Flow and this film opened you up a little bit, changed your tastes?

Howard: I don’t believe that music should be violent. It touches such a central place inside of us, it’s such a delicate place. It should never be violent. You can’t have guns and knives and swords and bats in the innermost place of your heart. We behave accordingly.

But there are elements of rap that I do like. Back in the day with De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest and Public Enemy – these people that talked about a positive image. Nas today, and Kanye West today. But there are other elements of it that I stay away from.

Curtis Jackson, the person I’ve met, he has such a positive message. Mr Hyde, that’s 50 Cent – he’s real. He’s very real. But he’s been created in order to survive that environment he grew up in. Once he’s made it through everything he has to make it through, you’ll see a change in his music. But he’s still dealing with the post-traumatic experience of 50 Cent, so that’s what he talks about.

Q: Is that important to you to do in your work, to always bring something positive?

Howard: You have to. There’s a good side to everybody. I try to show both the good and the bad in all these characters. I don’t water down the truth; even though I don’t like using the word nigger, in Hustle & Flow it wasn’t in the script one time but you heard it in almost every sentence. Why? Because in the time I spent down there, everybody I heard using it. So I would be remiss to not put it in there. Fortunately in this film, my character hated that word, so I could express my own ideas with it. But even in Hustle & Flow, he carried a strength about him that was encouraging. In Crash you have a guy with a strength about him that’s dignity, but he’s lost his integrity, so busy trying to hold on to his façade of dignity.

Q: Your character in this has some very interesting aspects.

Howard: Bama comes from a guy that 50 knew called Country. He was very soft spoken and would tell you that you hurt his feelings. And if you did not apologize for hurting his feelings, he would shoot you.

Q: Did you meet Country?

Howard: No, he was incarcerated. For the benefit of the rest of us!

Q: With all the buzz you’ve been getting have you been seeing a lot of projects coming your way?

Q: With all the buzz you’ve been getting have you been seeing a lot of projects coming your way?

Howard: You hear all the Oscar talk, and with people thinking you might get nominated they want to attach you to their film because if you get nominated that gets press for their film. But I’ve also gotten really good scripts from people who believe in what I can do. To play Thurgood Marshall, for New Line, or to play Joe Louis for Spike [Lee]. Those two opportunities – my life has changed in regards to that. But I know that it’s only changed because I learned to listen to a director, but the moment I stop listening it will return to the old way.