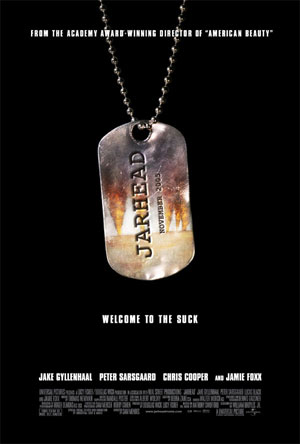

War is hell. We know that from watching Hollywood’s output of war movies. Now Jarhead comes along to show us another side of that – no war is hell, too.

War is hell. We know that from watching Hollywood’s output of war movies. Now Jarhead comes along to show us another side of that – no war is hell, too.

Anthony Swofford has joined the Marines, making “a wrong turn on the way to college.” He’s got a pretty girlfriend back home wearing his USMC t-shirt, and he’s got the spectre of his father to live up to, a Marine in Vietnam. We don’t learn a lot more about who Swofford is before the Marines – he has a sister in an institution, and his mom drinks and his dad doesn’t talk and he reads Camus – but that’s because when he enters the Marines he stops being who he was. The film opens at boot camp, a scene purposefully reminiscent of Kubrick’s now canonical take on military training.

Swofford is broken down and rebuilt into a new man, a Scout Sniper with the thirst for blood deep inside him. Like the rest of the guys in his squad there’s one thing he wants – action. And when Iraq invades Kuwait it looks like he’s going to get it.

But Jarhead isn’t about fighting – there’s not a single real firefight in the film. It’s the cinematic equivalent of blue balls as Swofford and friends go to the Saudi Arabian desert and spends months sitting around, only to finally be deployed and find that the war is over before they even got there.

Jarhead might be Sam Mendes’ first honest film. American Beauty suckered you in with its seemingly deep observations on the ennui and emptiness of life, but it was really a hollow and meaningless sham; an emotionally false sham. Somebody needed to put that plastic bag over Wes Bentley’s neck and tie it off. The Road to Perdition was a better film, but it was an exercise. The father/son story was hackneyed and without any real resonance.

But Jarhead is real, and part of that is obviously because it’s true. Anthony Swofford wrote the book Jarhead based on his real experiences in the First Gulf War, after seeing that the realities of the ground war were not being shown. I haven’t read the book, but the movie is in many ways a howl of rage at being forgotten.

It’s also a stinging rebuke to the entire military culture. A couple of months ago I interviewed Peter Sarsgaard, who co-stars in the film, what the reaction from the Right would be to this movie, and he claimed it wasn’t political. That sentiment echoed something his character says in the film, but in both cases it’s false. The film is political from beginning to end.

The training scenes are fairly straight-forward. We meet the other guys who will be in The Suck with Swofford (your average motley crew of stereotypes – the Hispanic, the nerd, the lunatic), and his flinty-yet-lovable sarge, played by Jamie Foxx. Foxx really has a thankless role here, and I don’t understand why anyone would want to take on this most well-worn of all war film characters. There’s no more shading that can really be brought to this guy – he’s a hardass, but because he cares. He loves his job and believes in what he does and believes in his men, even when he’s giving them incredibly harsh punishments. And if he singles Swofford out the most – well, it’s because he sees the most in him. Snore. Foxx manages to do a good job with the role, though, using his natural charisma to keep us interested in the cipher he’s been assigned.

But it’s once training ends that things start to get weird. Swofford’s squad gets called up while in a theater watching Apocalypse Now. The scene is the helicopter attack on the village, with Ride of the Valkryies booming and the men in the audience hooting and hollering. It’s violence porn; the men are getting off on the imagery of the destruction being caused because they’re imagining they’re going to be meting out similarly harsh damage soon enough. It’s a creepy scene, and Mendes dislocates us somewhat by having Swofford completely in with the crowd.

The use of Apocalypse Now isn’t accidental. The war is being fought in the shadow of Vietnam – both as a horror and as a crucible for the men. At one point helicopters buzz overhead playing The Doors – Swofford gripes that this is Vietnam music, can’t this war have its own sounds?

Apocalypse Now also serves to show us how these men had their expectations shaped by the media. This was a war full of guys who had never known war in their own lifetime, whose very concepts of what war is was dictated by films and TV and books. Not only was the almost complete non-starting aspect of the war going to be a letdown for these trained killers, but their very expectations – only amped by warnings from brass that there would be 30,000 casulaties in the first day, that chemical weapons would definitely be used against them – led to them being bewildered and confused and disappointed.

Jake Gyllenhaal is tremendous as Swofford. He’s buffed up to make you forget Donnie Darko (and he shows it off every chance he gets – Jake’s 98% naked for quite a number of scenes), but he still has those doe eyes. Swofford’s a tough character because I don’t think he’s actually all that likable, but Gyllenhaal keeps our sympathies at all times. Even when he’s about to shoot another Marine in the head for ratting him out.

Sarsgaard, I am sad to report, is another story. It’s not that he’s bad – I think Sarsgaard is one of the best young actors working today and I don’t think he can be bad – but he’s just got nothing to do in the film. He’s Swofford’s buddy and his spotter when they’re out in the field (not) shooting people, and he’s the “voice of reason” character who is usually the lead in war films (Swofford is most definitely not a voice of any sort of reason). He does get one great scene at the end, when he’s denied his one and only chance to kill anyone in the whole war, but other than that Sarsgaard is kind of hanging around a lot. Shame on Mendes for not finding more for this powerful and engaging actor to do.

Back to Sarsgaard’s claim that the film isn’t political. His character, as I mentioned, says the same thing in the film. One of the Marines is bitching about why they’re in the Middle East – to protect rich white men’s access to oil. Sarsgaard tells him that politics has nothing to do with it, that they’re there to do a job. Except that Mendes has ensured that politics are heavily sprinkled throughout. Not just in speeches (which pop up with some regularity throughout, as Marines seem to stop to take a moment to pontificate on a subject ranging from the lack of armor to the cruelty of Saddam), but in small ways. When the Marines get off their planes in Saudi Arabia an oil company banner greets them. At the end of the film, when the war is over, the Marines celebrate that they’ll never be coming back to the desert ever again. And the very depiction of the Marines – they’re all damaged and deadly, except for one, who happens to have a dark secret back home anyway – and the way that their service ruins their lives as their girlfriends and wives cheat on and leave them, is deeply negative. Jamie Foxx gives a speech about why he loves being in the Marines, but it’s delivered against the backdrop of an apocalyptic oil fire – his words carry less weight than the hellishness around him.

Mendes learned a lot on The Road to Perdition and he makes use of it here. Jarhead is a fantastic looking film, and it’s structured wonderfully. The film begins in areas where we’re comfortable – training camps and barracks – and then slowly begins to layer on the tedium and surreality of the deployment. By the time the oil fires start and the landscape has turned into some kind of Boschian nightmare, Mendes has slipped the shackles of familiar desert imagery (previous scenes recalled Three Kings and Lawrence of Arabia) and has made a new visual statement.

It’s his ability to capture the tedium of the Marines’ deployment that almost sinks Jarhead. The film feels long. It’s episodic, with no real through story beyond the broadest concept that these guys are in Desert Storm. And things start to sag in the middle, as Swofford and friends find ways to kill time in the wasteland (scenes that remind you of M*A*S*H, likely another source of war knowledge for these soldiers). The anti-climactic nature of the story itself means that the film sort of ambles to a conclusion, and that’s part of what made many people feel the book wouldn’t make a suitable film. I think Mendes pulls it off, though, and ends up delivering a very solid, funny and honest addition to the war film canon.

There’s one more thing that anyone walking into Jarhead has to think about, which is the film’s relationship to the current war in Iraq. It’s hard to see these guys who walk out of their war unscathed as such victims when we just lost the 2000th soldier in Iraq this past month. Maybe being bored out of your mind, completely unable to fulfill the violent brainwashing of your training, isn’t the worst thing that could happen to a soldier.