Cameron Crowe’s new movie, Elizabethtown, is like the shambolic southern rock that fills its soundtrack. Like Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Free Bird (now used twice to great effect this year), the film is too long, peaks too early and is really sort of all over the place.

Cameron Crowe’s new movie, Elizabethtown, is like the shambolic southern rock that fills its soundtrack. Like Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Free Bird (now used twice to great effect this year), the film is too long, peaks too early and is really sort of all over the place.

Which is why I loved it.

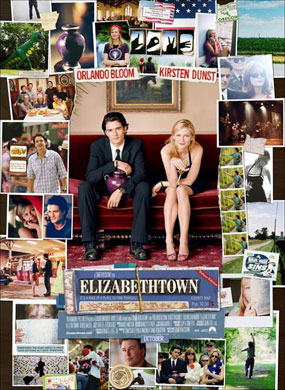

Orlando Bloom is Drew, a guy who designs sneakers for Mercury, a company that is sort of like Nike except that it’s run by a guy named Phil. Oh, wait… Anyway, Drew has designed the next generation in footwear, a sneaker called Spasmotica, which really should have been a warning sign from the start. Anyway, the sneaker is a disaster and will end up costing Mercury almost one billion dollars in losses. As Drew is getting ready to kill himself –in a very innovative way – the phone rings. His dad has just died while visiting his hometown in Kentucky.

On the way to Kentucky, in a completely empty red eye flight, Drew meets Claire, an odd and aggressive stewardess. Since she’s played by Kirsten Dunst we know that she can’t be that bad, and that their paths will indeed cross again. But before they do, Drew has to go to Elizabethtown and meet the family that he has never known, and learn about the kind of man his dad was, and the kind of place he came from.

It’s when Drew gets to Elizabethtown that he movie kicks in. The opening fifteen minutes includes some clever stuff, and some very lovely Jessica Biel (who has an incredibly tiny role), but it’s when the people of the town start lining the streets to wave, when this kid on a bike acts as his motorcade, that the Cameron Crowe magic kicks in.

What’s that magic? It’s twofold – one is that the guy has retained his journalist’s eye for the small moments in life. So many little scenes ring completely true – Drew alone in a hotel room, dialing pretty much everyone he knows just because he wants to talk to someone; Drew touching his first dead body and thinking he sees his father’s features curl in a small smile; sitting behind the wheel of a car on a lonely road while a great song plays – that they transcend the specificity of the moment to become universal. It’s the same thing Noah Baumbach does in The Squid and the Whale (my review of which will be done by this weekend, I swear to you). Both films take very specific, very exact places and times and situations and discovers the fractal inside of it – all experience is inside your experience.

The other bit of magic is that Crowe believes in what he’s saying. A lot of people are irked by the relentless positivity and – if you’re inclined to see it that way – cheesiness of Crowe’s films. I should feel the same way, but watching any of his movies it becomes obvious that the guy isn’t including the swelling pop song at that exact moment because he wants to manipulate you – it’s because he feels that it would be awesome to have that song at that moment. His happy endings and cathartic moments don’t always carry the imprint of reality, but they always carry the imprint of how he thinks. There’s not a dishonest moment in any Cameron Crowe film (except maybe Vanilla Sky, which had Crowe stretching outside of his usual space and trying on an unfamiliar genre).

Cameron Crowe has long been an avowed disciple of Billy Wilder. He even spent hours with Wilder, interviewing the cranky old director. The results ended up in the very enjoyable book Conversations With Wilder, which I think any fan of the movies should pick up. But while Crowe loved the director, I never believed that anything he made was really in Wilder’s vein. Wilder was mean. He had plenty of wit and humor, but he was acerbic in a way that I don’t think Crowe could be. Cameron Crowe loves his characters, all of them. There’s not a bad guy in Elizabethtown. On the other hand, I can think of some Wilder films – like One Two Three – where I don’t think the director could even stand a single character.

Crowe has said that Elizabethtown was his Hal Ashby film, and it does seem like Ashby is a better role model for him. Hal Ashby loved his characters completely, even the horrible ones (and the grotesque ones, like every one in Being There). But he also had a darkness in his best films that I think is beyond Crowe. That’s part of what I like about the guy, actually, in that he’s so much like the kid in Almost Famous who is so attracted to the darker side of things, but is never really part of it. Still, the whimsical aspects of Ashby suit Crowe nicely.

One area where Crowe beats Wilder and comes even with Ashby is his use of visuals. I think it comes from his love of music – there’s something so inherently visual about a good song. Many a night has involved me listening to my iPod and imagining movie scenes to go with the great songs I am listening to, which song would be great for the opening credits and which for a gun battle (there is a Sufjan Stevens song I would love to use in an epic, old school John Woo scene). There are a dozen beautiful moments in this film, and sure, they do call attention to themselves sometimes, but hey, you should be proud of your work.

The real misgiving that many people, including myself, had when the trailers for this film first hit was the leads – Orlando Bloom and Kirsten Dunst? Neither of these actors seemed up to the task of, well, acting. I’m happy to report back to you that for the first time in his career, I have seen Orlando Bloom actually act. And a lot of the time he does it well. His accent’s pretty damn good, actually, and there are some very good moments where he has to do a lot with just the slightest twitch of his features – like when he first sees his dad’s corpse – where he’s just sublime. There are other scenes, though, where he’s annoying and over the top in all the wrong ways. But more often than not he’s amiable and lovely and confused all in proper measures.

Dunst doesn’t fare as well. She has the slack features of the perpetually stoned, and the role of Claire needed an actress with a little something more going on in her eyes. Claire, you see, is sort of desperate and weird and pushy and lonely, the kind of qualities girls I attract seem to possess in spades, and generally unattractive. She’s a borderline stalker, and you need a girl with the right charm and cutes and maybe naïveté to make it work. That’s a tall order, and it’s one Dunst can’t fill. Surprisingly enough she isn’t as irritating as she in the Spider-Man films, and most of the rest of the stuff she’s in. It’s just that I can see why Drew falls for her in theory, in the script. On the screen it makes no sense.

One of the small pleasures of Elizabethtown is how it mildly eschews a traditional three act structure. It’s still essentially three acts more or less (although I do believe I could make the case for it being four acts), but the climax of the film comes and then Drew sets off on an extended road trip. Your interest in going down the back roads of the South and visiting Sun studios and the Lorraine Hotel and other small spots while listening to a mix CD is going to determine how you react to this. I get the impression that a lot of audiences will wonder why the hell the movie didn’t end – I found myself wishing that it wouldn’t. I want to see Crowe make a two hour film that’s just a road trip, and then I want to get that film’s soundtrack and take my own trip.

Sometimes movies just seem to dovetail with your own experience. My grandfather died just over a year ago, and there are moments here that resonated so much with me – especially a scene with the American Legion – I found myself near tears. There were actually a number of times I found myself near tears, but that’s how I sometimes react to powerful, true things. And the film, for me, is filled with them. I have also lately found myself deeply interested in southern rock and roots music and country, and as a corollary I have had a new interest in the south and its history. Here again I found the film on the exact same wavelength as me.

And it’s worth noting that part of the film’s pacing, that almost novelistic but really just meandering and friendly pace, is very southern. The south of the film isn’t filled with yokels and rednecks, and there’s not a racist concept to be had (although there’s also no one of color to be seen). Most interestingly, Crowe doesn’t make one of the film’s central conflicts – that the people of Elizabethtown blame Drew’s mother for taking his father, a beloved local hero, away from them – into a city vs country issue. Drew and his family have lived in Oregon, not the kind of state one associates with sprawling metropolises. There’s not really a moment where anyone learns the value of a downhome community, just the value of knowing where you’re from.

Elizabethtown’s not perfect by any means. Crowe goes for slapstick once too often, and the climactic moments at the father’s memorial service keep brushing up against over the top. Susan Sarandon, as the mother, is given a silly storyline where she becomes hyperactive to draw her attention from her sudden loss; it culminates in a comedy routine and tap dance that probably sounded better than it is (although Crowe shoots her wonderfully in the dance). Drew’s sister, played by the always lovable Judy Greer, gets really short shrift as well.

And strangely, Crowe doesn’t give Drew a big cathartic moment. I wonder if that’s on the cutting room floor (the film was longer when screened at the Toronto Film Festival) or if he left it out, letting the road trip be the longer catharsis. I mean, that’s what the roadtrip is, fully and completely, but I have to admit I expected a big emotional outburst from him.

And as always, Crowe sometimes goes for the obvious moment when he should have maybe held back. But like I said before, it always feels like it’s coming from the heart, so it’s easy to forgive the guy his occasional lack of restraint.

Like many Cameron Crowe films, I expect this one to divide you, my dear readers. Honestly, if you’re not into what he does by now, this film won’t be the one that sells you. But if you’re open to the experience, Elizabethtown is one of the sweetest, funniest and better films of the year.