BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

BUY IT AT AMAZON: CLICK HERE!

STUDIO: Lions Gate

MSRP: $27.99

RUNNING TIME: 97 min.

RATED: R

SPECIAL FEATURES:

• Commentary

• Deleted scenes

• Featurettes

David Duchovny spent nearly a decade on The X-Files, even writing and directing several episodes himself. Outside of a brief appearance as a conspiracy theorist/hand model in Zoolander, his post-Mulder career hasn’t been especially notable, so it would come as no real surprise if his feature film debut behind the camera would involve material similar to that which made him famous.

But House of D is nothing like The X-Files. Which makes it that much more surprising. Mostly because I kinda liked it anyway.

The Flick

First of all, let’s get the significance of the title out of the way: it’s a women’s house of detention in New York City circa 1973, where 13-year-old Tommy (Anton Yelchin) converses with an unseen inmate who dispenses life lessons through the bars of her second-story cell. We first meet Tom in his mustachioed Duchovny incarnation as an artist living in present-day

Despite warnings from police and family, Giant Randy insisted on giving his "deep welcome" to all newcomers in the neighborhood.

Young Tommy lives in

Duchovny approaches this coming-of-age story and its often hackneyed and unlikely elements with confidence and sincerity (and there’s no reason he shouldn’t, since it’s semi-autobiographical), but with the inherently maudlin nature of the material, he’d be utterly doomed without a capable cast. Fortunately, Yelchin (whose delivery eerily integrates the inflections of both Leoni and Duchovny) brings an uncanny maturity to the part, mischievous and intelligent but not gratingly precocious, which certainly makes the sporadic platitudes easier to stomach.

Trepanation and tequila-dipped filter-tips: the latest club craze.

Yelchin’s protagonist also has a handful of colorful supporting characters. In spite of some distracting fake teeth, Williams shows unexpected restraint in a simpleton role that, frankly, could’ve been downright excruciating (rather than just occasionally overplayed), and his friendship with Tommy is wholly believable, even if it’s in a sort of boy-and-puppy sense. Songstress Erykah Badu turns her convict’s peculiar relationship with Tommy into some of the film’s more entrancing moments, and Frank Langella and Orlando Jones make brief but amusing appearances. I suppose there should be something creepily Oedipal about Duchovny casting his real-life wife as his fictional mother, but at least Leoni gives an honest performance in a thankless role.

During its brief theatrical run, Duchovny’s feature debut took a real critical thrashing, and I have to admit that had absolutely zero impact on my enjoyment level, which was far greater than I’d anticipated considering my usual tolerance for tearjerkers. A slyly charming assembly of overt sentimentality and quirky beats (sometimes surreal – the butcher shop owners Tommy works for feel like David Lynch leftovers), House of D never gives the impression of an egregious vanity project, offsetting some shameless melodrama with unsympathetic actions, and a keen sense of period tone and nostalgic details of adolescence. Duchovny gets a little carried away with the application of syrup during the implausibly tidy closure of the framing narrative’s overlong backend, and the tragic historical events that originally sent Tom on his distant guilt trip don’t adequately explain an apparent 30-year emotion-hole in his life, but solid performances and poignant moments help the film transcend its intrinsic angst and copious clichés.

7.5 out of 10

Langella made a decent Tall Man, but the retro redesign of the sentinel balls was one of the more questionable aspects of the remake.

The Look

I’ve never seen

8.5 out of 10

The Noise

Though it’s a dialogue-driven film, there are several poppin’ 70s cuts from the likes of Stevie Wonder, the James Gang and the Doobie Brothers, all in a Dolby 5.1 clarity far superior to 8-tracks.

8.0 out of 10

A demonstration of Duchovny’s astute eye for composition…

The Goodies

Duchovny delivers a solo commentary track, and while it’s cordial and informative, he really needs someone else to play off of to minimize his monotone — the 15-minute post-screening Q&A session with Duchovny (which for some reason is called “All Access Festival Pass”) gives much of the same information in condensed form, and is a much more engaging display of the actor’s droll manner. Still, the card-carrying Mulderettes (or whatever female X-Files zealots call themselves) should be moist with joy at the prospect of this much Duchovny.

The 11-minute making-of featurette “Building the House of D” is your fairly standard “talking heads” promotional puff, while “The Old Neighborhood” focuses on the location shooting that took place in New York City. An alternate ending (which is pretty terrible compared to the one in the film) that lists the reasons why the detention house was closed, and four other deleted scenes that probably would’ve stilted the pace (one jumps back to

7 out of 10

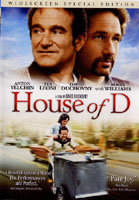

The Artwork

A curious deviation from the theatrical poster, the cover completely and racistly eliminates Erykah Badu’s entire presence. It also downplays the retard aspect, giving a normal-looking floating head of Williams beside Duchovny (who’s actually only on-screen for a few minutes) while telling us very little about the film itself.

4.0 out of 10

Overall: 7.7 out of 10