Holy shit, this column DIDN’T go on a two-month break again!

Holy shit, this column DIDN’T go on a two-month break again!

In case some of you folks haven’t been aware, Creature Corner has been reanimated in a big way. Brit deity Dan Whitehead has taken over the reins and is slowly but surely guiding that bitch back to a level of greatness. Expect more cooler changes down the road. But what I want to do now is simply pimp our "sister" column over there, Reader’s Rites. Same concept as The Chewer Column, except with that icky and depraved Corner sensibility. Go check it out! I know there’s some killer stuff coming up on the horizon.

Anyway, Chewer Andrew Clarke is back with more filmic ramblings (check out his previous Chewer Columns here and here). So sit back and enjoy…

Why Bad Movies Are Bad and Why Worse Ones Are Great

By Andrew Clarke

Member since 6/17/2004

Video Editor in London, EN

Born 2/20/1976

“But you know I saw this movie last year called er, ‘Basic Instinct’. Okay now. Bill’s quick capsule review: Piece-of-Shit… Satan squatted, let out a loaf, they put a fucking title on it, put it on a marquee, Satan’s shit, piece of shit, walk away. Anyway, so after I’d seen it seven or eight times…”

“But you know I saw this movie last year called er, ‘Basic Instinct’. Okay now. Bill’s quick capsule review: Piece-of-Shit… Satan squatted, let out a loaf, they put a fucking title on it, put it on a marquee, Satan’s shit, piece of shit, walk away. Anyway, so after I’d seen it seven or eight times…”

— Bill Hicks

Bad movies exist and sometimes we watch them. A lot. Why? Bear with me:

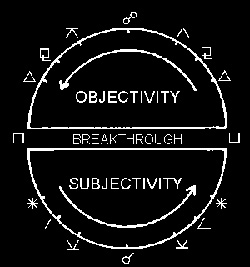

A film is just thousands of images strung together to give the illusion of movement when projected in sequence onto a screen. This is the ‘objective’ film, the thing that exists in the real world. It can be looked at, lost, bought, stolen, manipulated, measured and burnt. It is the film-as-artifact. This film can be spoken about objectively, in terms of mise-en-scene, editorial technique, film degradation, colour saturation and a thousand other sexy technical things.

Film-makers will talk to their fellow film-makers in these terms as shorthand for communicating what they want to achieve. People on Internet message-boards will use these terms when they want to sound like film-makers or otherwise impress fellow message-boarders into thinking they are clever.

But when we talk about the films we love, or hate, we will talk about character, plot, theme, atmosphere or excitement. We will describe it as ‘gentle’, ‘sweet’, ‘lovely’, ‘funny’, ‘stupid’, ‘vicious’ and plenty more bizarre adjectives that the objective film obviously isn’t.

This is because we, as an audience, don’t care about the objective film. It is entirely beside the point. Even for film-makers it is, or should be, purely a means to an end. For the real magic of film is not the trick of the eye that creates a sense of movement out of successive images, it is that those images can create worlds, people and stories utterly tangible and often so strong the real world is utterly overwhelmed.

This is because we, as an audience, don’t care about the objective film. It is entirely beside the point. Even for film-makers it is, or should be, purely a means to an end. For the real magic of film is not the trick of the eye that creates a sense of movement out of successive images, it is that those images can create worlds, people and stories utterly tangible and often so strong the real world is utterly overwhelmed.

The final end for film-makers is to create a ‘subjective’ film; a film which the audiences experiences rather than observes.

The ‘objective’ film is not the ‘real’ film.

The magic works like this: the human brain will always try to find the connection between things. If you put two things together, the brain will try and work out how they are connected, even if they are not. Politicians and salesmen will do this all the time; putting the words ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’ and ‘Iraq’, or ‘Healthy Diet’ and ‘Big Mac’, together in the hope that, after a while, people will believe they have something to do with each other; the weight of the average republican is proof that it works. In this way, humans are gullibility machines.

Film-makers play on this gullibility, manoeuvring images together so that the audience will perceive specific connections between them and it is out of this play of connectivity, built out of the spaces in between the ‘objective’ film, that the ‘real’ film emerges. We will start to despise a particular face when it pops up, love another, fear a door being opened, long for the light and so on. In this way we are willing participants in this game. We want to be taken up, en-ravelled and filled with a film. This is the contract we enter into – that the film-maker will attempt to create a coherent set of connections and we will try our hardest to find them.

If we have a particularly strong attachment to a genre or a particular image we will go further in finding these connections between the images, often to the point where we fill in connections that are not there or, at least, not put there deliberately by competent film-makers. This is why ninja fans will enjoy any Piece of Shit with a ninja in, why Star Wars fans will fill in continuity for some of the less glorious moments of those films (something Joss Whedon has called a ‘fan wank’), and why we are extremely interested in porn films for 5-10 minutes at a time.

If we have a particularly strong attachment to a genre or a particular image we will go further in finding these connections between the images, often to the point where we fill in connections that are not there or, at least, not put there deliberately by competent film-makers. This is why ninja fans will enjoy any Piece of Shit with a ninja in, why Star Wars fans will fill in continuity for some of the less glorious moments of those films (something Joss Whedon has called a ‘fan wank’), and why we are extremely interested in porn films for 5-10 minutes at a time.

It’s this emergent film, which hovers halfway between the screen and the audience, that we are all in the film-watching game for. It is immeasurable, elusive and, like the very best magic, it happens everyday.

It is this distinction which allows Nick to hate on the excellently made Cold Mountain and Devin to actually quite like the Piece of Shit Fantastic Four.

Now, the purpose of this distinction is to explore what it is that makes a bad film bad. Let’s take The Day after Tomorrow, which is a Piece of Shit (great trailer though). It IS awful but, as an objective film, absolutely succeeds in creating a subjective film, of using all the state of the art film making techniques to create the world, characters and story it wanted to create. It’s just that the film Mr. Emmerich and friends wanted to create was a trite, overblown and hypocritical mess. We entered into the contract in good faith, found the film Emmerich wanted to show us, and became incredibly annoyed at how dumb it turned out to be.

These sorts of bad films fill cinemas every week. There are thousands of them. They commit mediocre crimes against humanity and should be ignored.

Much rarer, and much more precious, are films that utterly fail to create any sense of connectivity at all; films that, far more than dully being bad, simply do not exist as ‘real’ films at all; films made by film-makers that utterly fail to understand the difference between ninety minutes of pictures and a movie; films not even good enough to be called Pieces of Shit.

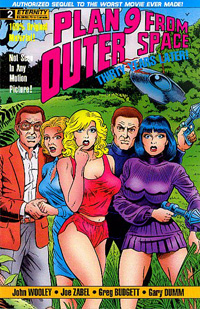

Let’s use two famous ones as examples: Edward D. ‘for Depp’ Wood’s Plan 9 From Outer Space and Uwe ‘Barn-door’ Boll’s House of the Dead.

Let’s use two famous ones as examples: Edward D. ‘for Depp’ Wood’s Plan 9 From Outer Space and Uwe ‘Barn-door’ Boll’s House of the Dead.

These are films so bad that they never allow you to enter in to the gullibility contract with them and create that ‘subjective’ film. Any time it does anything to build up any sense of coherent connectivity between its images, it immediately tears it down again, forcing you back to look upon its blank objective self. These films are entirely, fabulously naked.

They have dialogue so bad the lines are practically koans:

“Events in the future will affect us all, in the future.”

“Why do you want to be immortal?”

“So I can live forever!”

Both have actors who can’t act, given roles so thin that they are forced to flail about in a flop sweat of panic or to simply slouch blankly in the corner of the frame, and given barely grammatical lines that they often can’t even remember.

Both have flagrant stock footage abuse, random tone and pace fluctuations and rather hopeful special effects.

Both have framing devices that only serve to constantly distract you from the actual film – endless tangential narrators in Plan 9 and flashes from the actual video game in HOTD.

Both have sets that might as well have neon signs above them screaming ‘FAKE!’ – A rave scene with twenty people in the bright sunshine, a house of the dead the size of a shack, an aeroplane cockpit made of a piece of bent cardboard and a plastic graveyard that might collapse if an ant were to sneeze on it.

Smarty-pants film professor Terry Black (Screenwriter on Tales From The Crypt) reads out a list on the overlong but fun documentary on the Plan 9 DVD of all the things he felt the film did badly. The list runs to 82 flaws, not counting repeats.

Smarty-pants film professor Terry Black (Screenwriter on Tales From The Crypt) reads out a list on the overlong but fun documentary on the Plan 9 DVD of all the things he felt the film did badly. The list runs to 82 flaws, not counting repeats.

In an 80 minute film, it really couldn’t be any worse.

All films have moments where the connectivity breaks down and you are forced back into looking at the objective film for a while. This is referred to as ‘being taken out of the movie’. But this implies a movie to be taken out of.

With many ordinary bad movies we can gain entertainment from finding connections the film-makes did not intend and ‘reforming’ them. We are breaking the contract and forcing an interpretation onto the film-makers instead of the other way around. 80’s action movies, for example, rife with male bonding and puerile attitudes to women, can easily be reformed into glorious gay epics. The Passion of the Christ can be reformed into the ultimate S+M Jesus porno, complete with climactic bloody facial onto an agape centurion. But these films still manage to create that ‘real’ film, even if they were not the ones the film-makers intended.

But these wonderful, terrible non-films have no ‘real’ film to be taken out of or to reform. Anything gained from the film will be brought 100% by the audience for the objective film gives you nothing at all.

This can be entertaining in much the same way as finding faces in clouds can be entertaining, or by laughing at it smugly in true MST3K fashion. It is far more difficult though, and far more fascinating, to just revel in the utter un-ness of them, like staring down a bottomless hole or up into a starless night. It is vertiginous, but strangely comforting, like a mild euphoric hysteria.

Of course, one could just create a film of nothing at all, but this would be like simply turning the lights out in your room. It’s a cheat, and does not have the same effect. Consider, though, watching a film of white noise and static for two hours: It would become hypnotic after a while, to the point where you wouldn’t be able to turn away from it. You might even start to see the people in the TV. It would, at least, be preferable to watching White Noise.

Of course, one could just create a film of nothing at all, but this would be like simply turning the lights out in your room. It’s a cheat, and does not have the same effect. Consider, though, watching a film of white noise and static for two hours: It would become hypnotic after a while, to the point where you wouldn’t be able to turn away from it. You might even start to see the people in the TV. It would, at least, be preferable to watching White Noise.

There are paintings that consist of six inch square canvasses of a uniform green colour. Nothing else. The point these terribly clever painters were getting at is that some things can not be represented nor understood. It is in studying the utter lack of painting – of trying to react to it as a normal painting – that we begin to ponder that which can not be painted: the ineffable, the sublime and the utterly alien. These are the paintings of the face of God.

So am I suggesting that you can see God in Plan 9 From Outer Space?

So am I suggesting that you can see God in Plan 9 From Outer Space?

Sure, why not? If you can see shadows in space, dammit, you can see anything. But instead of just giggling and turning away from it, try genuinely attempting to enter into that gullibility contract with it, try to view it as if it were a real film, and see where it gets you. It is impossible of course, just as seeing God in a square of green is impossible – your rational brain will scream ‘the gravestone is fucking wobbling!’ – but, as film lovers, it is a rare and extraordinary experience to have a film that utterly defeats your attempts to watch it.

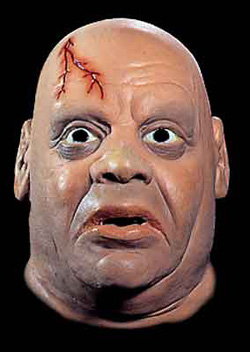

Now, no film is perfect, and no film is perfectly bad. Both Plan 9 and House of the Dead have sequences where they rise up and create a ‘real’ film. There’s ten minutes or so about half an hour into HOTD when the dead are chasing the alive through the woods that succeeds in being a rather dull horror movie. It is thankfully undermined when we find out the dead have locked one of the alive in a portaloo. Plan 9 wins this particular round by having its slightly creepy sequence (where the heroine is chased through the graveyard) ruined only thirty seconds in by Tor Johnson failing to get out of his grave.

And so dear, dear readers, we should cherish Uwe Boll’s movies. Yes, that really is the conclusion of this article. It is too easy to use him as a punching bag and it is hypocritical to hate him while holding some, however ironic, affection for Ed Wood’s films – no matter how cute Johnny Depp was in the movie. While films such as The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra merely seek to echo the bad movies of the 50’s, Uwe Boll achieves the far greater goal of updating their awfulness into today’s ultra modern film-making grammar and techniques. It would be a work of genius if it was in any way deliberate. As it is, his films are works of joyful incompetence that would only be ruined by any self awareness or, heaven forefend, an increasing of his skills to the point where he becomes just another bad horror-film director.

And so dear, dear readers, we should cherish Uwe Boll’s movies. Yes, that really is the conclusion of this article. It is too easy to use him as a punching bag and it is hypocritical to hate him while holding some, however ironic, affection for Ed Wood’s films – no matter how cute Johnny Depp was in the movie. While films such as The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra merely seek to echo the bad movies of the 50’s, Uwe Boll achieves the far greater goal of updating their awfulness into today’s ultra modern film-making grammar and techniques. It would be a work of genius if it was in any way deliberate. As it is, his films are works of joyful incompetence that would only be ruined by any self awareness or, heaven forefend, an increasing of his skills to the point where he becomes just another bad horror-film director.

Now the original pitch for this article was to examine why we seem to genuinely love certain bad movies so much. I was going to discuss DTV action movies, my strange fascination with ‘Hudson Hawk’, overly sequeled horror franchises and about 90% of the films released between May and the end of August. George has my apologies but I found the above piece far more interesting to write. [Note from George: I don’t recall anything about DTV action films or Hudson Fucking Hawk, but thank GOD you changed it, Andrew. We’ll leave that other stuff for the message boards.]

But to answer the question: We enjoy bad movies because we are stupid, lazy and immature. Walk away.

Got an idea for The Chewer Column? Let me know! Got a comment or two on an article? Voice it! Email me at GeorgeMerchan@gmail.com with CHEWER COLUMN in the subject line.