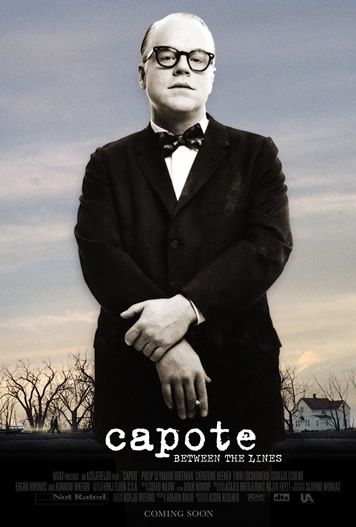

Some films are nothing more than showcases for great performances. In many ways, that’s exactly what Capote is – I don’t know if it could work with someone other than Philip Seymour Hoffman in the title role. At times incredibly fascinating and at others dreadfully slow, Capote is always kept aloft by the amazing performance at its center.

Some films are nothing more than showcases for great performances. In many ways, that’s exactly what Capote is – I don’t know if it could work with someone other than Philip Seymour Hoffman in the title role. At times incredibly fascinating and at others dreadfully slow, Capote is always kept aloft by the amazing performance at its center.

The film isn’t a full biopic of author Truman Capote; rather it’s a snapshot of the period when he was writing his best known work, In Cold Blood. Truman is the toast of New York’s intellectual scene, a much in demand party guest, when he reads a story in the New York Times about the savage murder of an entire family in a small Kansas town. He immediately calls his editor at the New Yorker and says that this story is what he wants to cover.

Truman enlists his childhood best friend, Nell Harper Lee, who as the film is taking place has just sent out her one and only novel, To Kill A Mockingbird, to publishers. Truman is flamboyant and flaming, sort of the ur-queer, and he knows that the Midwest probably won’t accept him easily. The quiet but forceful and boyish (is she gay as well? The film hints but never answers) Nell serves as Truman’s buffer as they deal with the local police at the still-fresh crime scene, as well as the other folks in this middle of nowhere town.

The early scenes crackle with energy. Catherine Keener is Nell, and she and Hoffman have a weird chemistry that feels exactly right. If someone were to make a weekly show where Truman and Nell travel to small towns and solve murders, I would tune in religiously.

But once the killers – small time hoods Perry Smith and Dick Hickock – are captured, Nell drifts out of the picture. Truman becomes fascinated with Perry, a rough edged killer with a sensitive soul. The two share a similar history, and Capote sees maybe an alternate Truman behind those bars. Soon he becomes deeply involved in their case, finding them adequate representation after their initial trial is shockingly fudged.

Soon Truman’s life begins to focus on just this prison, and just this killer. Nell’s book is published, and made into a movie – but these don’t really register with Truman. Jack, his lover, wants to get away with him so he can get to writing. Truman wants to spend time in Kansas, interviewing Perry endlessly.

But even that becomes twisted, and Truman realizes that as long as these men keep filing appeals and avoiding their execution, his book has no ending. Slowly Truman becomes a monster, focused only on himself and his book. Everything else is an obstacle and the pain of others matters only in how it inconveniences him.

Capote is brave for giving us this portrait of the artist as a complete asshole. It’s easy to start seriously disliking Truman, and it’s only Philip Seymour Hoffman’s innate soulfulness that makes you willing to keep up with him until the end of the film, until the long delayed but inevitable execution. Along the way Truman lies to Perry and manipulates him to get the juicy details of just what happened that night in the murder house.

Capote is a first film for screenwriter Dan Flutterman (best known as a sitcom actor) and the first narrative feature for director Bennett Miller, who directed the documentary The Cruise, about oddball New York City tour guide Speed Levitch. Flutterman has written a script that could probably easily be turned into a play, and that’s a compliment. It’s a script that’s about words and acting, something very rare. And it feels true to life.

Maybe too true to life. After the initial trial, Truman returns to New York and often flies to Kansas to meet with the killers. I realized halfway through that in an average biopic, there would be a condensing of the timeline here – Truman would fly to Kansas maybe once, perhaps twice. In this film it feels like a dozen trips, like Truman is constantly going back and forth and we’re getting lots of establishing shots of the prison and the guards leading the writer in. Again and again. It’s tough because as Truman becomes more solitary the film loses delightful supporting actors who could have lent it a light. Again, it feels like something that is quite true to the reality, but as a moviegoer I wouldn’t have minded some tweaks to maybe keep things hopping.

In fact you know that your film is not hopping when a character bemoans, “When is this going to end?” and your audience feels his pain. As much as I enjoyed the story and the way it was being told, I was feeling every minute tick by in the second half of the film.

I wonder if that torpid pace will hurt Hoffman’s shot at major awards love. I hope not, as he deserves it. At the start of the film you’re desperately aware that this is someone playing Capote, since the character has such a distinct voice and stylized mannerisms. But as time goes on, and as we realize that maybe we’ve been watching Capote playing Capote, Hoffman sinks into the role. That’s acting – it’s not about delivering big speeches with big emotion, but rather about making you forget you’re watching acting. Allowing yourself to be so consumed by the character that the audience is never thinking “Philip Seymour Hoffman went into the room” but “Truman Capote went into the room.” That’s a tall order when you’re an actor like Hoffman, who has been in dozens and dozens of high profile films and who is a unique presence to say the least. But he pulls it off with a magnificent flourish.

Chris Cooper has a tiny role as a police chief, one which I kept expecting to mean something, but which never really did (don’t get me wrong, it has meaning within the story and themes, but the role is really a glorified cameo). He’s just one of a number of actors in small roles who add plenty of class to the film. Perennial third string actor Clifton Collins Jr gets a real boost as Perry, more than holding his own with Hoffman and imbuing his character with the right conflicted aspects. You believe he killed those people, and you like him anyway – which makes it a little easier to sympathize with Truman. To an extent.

The best biopics are ones like this, ones that don’t try to tell the whole sweep of a life but rather examine one aspect. It’s like a fractal – when told well the whole story will be reflected in this one piece. Capote achieves that, but at the expense of some patience. This is a film that isn’t long but could stand to have fifteen minutes judiciously sliced from it.