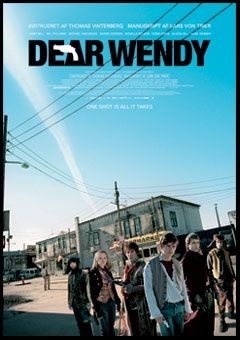

I come to you not knowing how to take Dear Wendy, the new film written by Lars von Trier and directed by Thomas Vinterberg, the cofounders of the Dogme movement. More than Dogme, though, von Trier is best known these days for his films Dogville and Manderlay, which are both hypercritical of America – and the fact that the Danish filmmaker has proudly never stepped foot in this country. Dear Wendy is certainly no Dogme film, but it is another salvo in von Trier’s self-righteous critique of the US. And in his hands it surely would have been a didactic bore. But Vinterberg takes it and does… something with it.

I come to you not knowing how to take Dear Wendy, the new film written by Lars von Trier and directed by Thomas Vinterberg, the cofounders of the Dogme movement. More than Dogme, though, von Trier is best known these days for his films Dogville and Manderlay, which are both hypercritical of America – and the fact that the Danish filmmaker has proudly never stepped foot in this country. Dear Wendy is certainly no Dogme film, but it is another salvo in von Trier’s self-righteous critique of the US. And in his hands it surely would have been a didactic bore. But Vinterberg takes it and does… something with it.

That’s vague, but even weeks after seeing Dear Wendy I am mixed up about the film. On one level that’s obviously the sign of art – something that is truly thought-provoking can’t be digested immediately. I suspect that I will need to see Dear Wendy again before I can really figure out whether this is a great film or if it’s full of horseshit – but it’s almost certainly one of those two things. In the meantime, bear with me as I muddle through this.

The story is almost ludicrously simplistic and representative – set in a mining town somewhere in the American Southwest, Dear Wendy is about a group of pacifist gun lovers who end up destroyed by their own passion. Jamie Bell, who has spent the last couple of years playing as far from Billy Elliot as possible, is Dick, a young man who can’t hack life in the mine. In his town that makes him less, and an outsider. But when he discovers a small antique gun, he is filled with self-confidence. A mutual respect for guns leads him to bond with a co-worker at the local convenience store, and after recruiting more misfits from town – a cripple, a shy and flat-chested girl, and an annoying dirty kid – they become the Dandies.

The Dandies meet in an abandoned section of the mine. There they study up on guns and practice with their firearm “partners.” Each Dandy gives their gun a name (the titular Wendy is Dick’s gun), but they are not allowed to bring the weapons out of the mine, for fear of “waking them up,” and hurting or killing someone. As time goes on the Dandies become a society unto themselves, dressing in flamboyant Old West fashions and parading through town – the guns give them self-confidence to be themselves.

This is the best part of the film. Vinterberg has assembled a fine cast, even Chris Owen, believe it or not. You probably remember him best as The Sherminator from the films, but in American PieDear Wendy he plays the crippled kid with an incredible soulfulness. He’s not only believable as a cripple physically, he’s believable psychologically – he doesn’t bemoan his situation or expect much special treatment.

Alison Pill plays Susan, the shy girl, and Michael Anganaro is Chris Owens’ younger brother, who joins the Dandies without a gun. Both are good – Pill is enchantingly pretty in an offbeat way – but Anganaro has a severe case of child acting. He was also in this year’s Lords of Dogtown (a movie that captures youth bonding as well as this one, by the way), and he was too precocious there as well.

In the end it’s a showdown between Bell, who is quickly maturing into a truly good and surprising actor, and Mark Webber, who plays the co-founder of the Dandies, for the best actor title in Dear Wendy. Both are powerful, and both act wonderfully with just their eyes, but for me Webber might edge out Bell – he has less to do, and his character is less obvious than the rest, but he remains completely enthralling.

I could have watched a film about the Dandies for much longer, but as the movie moves into the third act, it feels the need to shake things up and start making statements. It’s here that things really go off the rails narratively, while the ante is upped visually. We meet Sebastian, a black kid who Dick knew growing up. Sebastian’s in trouble – he shot a guy someplace – and most unrealistically he is placed into Dick’s custody. The film starts melting down right here.

Sebastian finds the Dandies to be a bunch of nuts, and that’s fair enough, although I resented him for it – I like those kids and their weird obsession, even if I don’t understand it. But what happens now is that Sebastian is the only kid with real world gun experience, and it seems like as soon as he joins the purity of the group is tarnished. Things start going wrong. And of course the rest of the kids are white, so there’s a sudden racial element introduced.

But what is the racial element? The film’s so vague here and its message so very muddled that it actually drifts into racism. Sebastian is a crook, a criminal and a killer. He’s moving in on Susan, who Dick maybe loves. And he thinks the Dandies are pretty square. He’s everything a stereotypical black character would be, except that he is suddenly shown to maybe have some depth. But by then it’s too little, too late. It feels like von Trier is saying, “Hey, be nicer to the niggers!”, a grotesquely mixed message.

The story comes to a headscratchingly unrealistic action climax, where a series of nonsense events put the Dandies into armed conflict with the might of the local and state police. The film allows its metaphor to overtake the story here – Sebastian’s confused old aunt is so afraid of non-existant marauding gangs that she won’t leave her house to walk down the block, and it’s the Dandies’ well-meaning but inept attempt to help her that leads to bloodshed. I like the concept that the people in this town are paralyzed by boogeymen, much like modern America’s really irrational fear of terrorists, but the microcosm of the town renders this all laughable. The commentary is lost.

While the circumstances leading up to and the events of the climactic gun battle are ridiculous, Vinterberg shoots is wonderfully. Here the film veers as far as possible from Dogme – we see an X-ray of a bullet hitting someone, much like in David O Russell’s Three Kings; a sharpshooter’s mental calculations are shown onscreen as math. It all looks great, and it made me want to go home and watch The Wild Bunch.

But that’s the problem. Vinterberg seems to be using the Western in what he thinks is an ironic way, without realizing that the entire genre was largely subverted to critique its own conventions from the 60s onward. Vinterberg seems to have gotten the look and feel of Peckinpah, but I wonder if he’s understood the man’s films. I wonder what his take on The Searchers would be. I fear it would be strikingly literal, a reading with Ethan as a hero.

Dear Wendy is a weird movie. It’s a beautifully made movie. It’s a stirringly acted movie. It’s also a frustrating movie, a movie that feels like a very artfully written but poorly thought out high schooler’s blog harangue. It wants to be controversial, it wants to make Americans mad at the way that they’re portrayed, but the problem is that Americans will watch this movie and identify with the Dandies as strange and twisted but noble outsiders. Instead of turning the Western genre around to comment on the people who created it, Vinterberg finds that the genre itself has overpowered him. I like Dear Wendy more than I am annoyed by it, so I’m giving it a good score. But it also deserves that because it’s one of the only films in maybe years and years that has left me so torn, and made me spend so much of my brainpower trying to parse what the hell was being said. A film that does that, even without being totally successful as a whole, is one I am happy to recommend for you – if not to enjoy, at least to chew over.