There’s a long history in Hollywood of shelved projects, abandoned franchise dreams, stalled careers, and entire genres that lost favor or profitability. 9 times out 10 these problems and failures are the result of a myriad of complex issues and contributing factors. Sometimes though… Sometimes you can pretty much pin everything on one film that fucked it up for everyone. Whether it’s a movie that killed a rival project, destroyed a filmmaker’s career, squashed some brilliant idea, or took the shine off of an entire genre, this CHUD List will catalog the films that were just total, unapologetic Cockblocks.

———-

———-

Day 8 (Tod Browning’s Career)

Joshua Miller (Email • Facebook)

———-

THE COCK: Director Tod Browning’s career.

THE COCK: Director Tod Browning’s career.

In 1932, Charles Albert “Tod” Browning, Jr., was white hot. After shepherding a string of Lon “Man of 1000 Faces” Chaney films to success, Browning was one of the premiere directors in the horror/thriller genres. He was Carl Laemmle Jr.’s natural choice to helm Universal’s surefire hit adaptation of the Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston’s hit stage play, Dracula. Surefire hit it was. With the freedom to craft whatever the hell he wanted as his next fright-fest, Browning set out to truly horrify his audience…

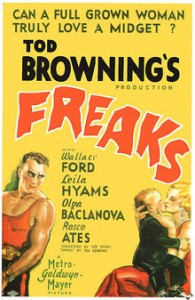

THE BLOCK: Freaks (1932)

THE BLOCK: Freaks (1932)

Browning’s adaptation of Tod Robbins’ short story “Spurs,” about a conniving circus trapeze artist who marries then cuckolds the circus sideshow’s wealthy midget. Unlike the make-up covered Universal monsters, the “freaks” of Freaks where actual sideshow performers, many of whom where quite deformed. Audiences and critics were not only scared and horrified, they were revolted. The film itself was treated like a freak – panned and banned around the world, it was not just a flop, it was reviled. Browning went from white hot to absolute zero freezing over night.

How it Went Down:

Tod Browning had lived a life as bizarre and tragic as the characters in his films. While still an actor working in silent films, Browning crashed his car into a moving train, killing fellow actors Elmer Booth and George Siegmann. More relevant, as a young man he had run away from home to fulfill that ultimate early-20th-century cliche – joining the circus. It was no doubt his time spent performing in sideshows that drew him to Robbin’s short story. “Spurs” was Browning’s dream project. Shortly after the story was published, in 1923, Browning convinced MGM to purchase the rights. The project languished, as Browning was unable to convince the studio to move forward with his vision. Sure, he was delivering hits with Lon Chaney, like The Unholy Three, The Unknown, and London After Midnight, but Chaney was of course garnering all the prestige. Browning may have had the clout to get “Spurs” optioned, but he couldn’t get it made. Then Chaney died and Dracula happened.

Dracula was never Browning’s film. For one thing, he didn’t want Bela Lugosi (who starred in the stage version). Browning’s vision – whether misguided or imaginative, we’ll never know – was to have Dracula a mostly off-screen presence. But the studio just wanted an aping of the stage play, and Browning was forced into a more conventional and uninspired approach (uninspired for him). Universal reaped what they sowed here, and were not happy with Browning’s finished product. But Dracula was a monster hit (pun!) nonetheless. Browning could now finally make “Spurs” happen.

MGM’s production supervisor, Irving Thalberg, wanted Browning to make a film out of Maurice Leblanc’s detective hero, Arsène Lupin, but Browning declined. He likely knew it now or never, and he wanted to visit the circus. Thalberg consented, though was very wary of the project. Browning wanted Myrna Loy and Jean Harlow to star in the film, but Thalberg wouldn’t grant him any stars. Undeterred, Browning moved forward with his vision, casting actual sideshow “freaks.” Browning probably should have seen the storm clouds coming, as the “freaks” presence on the studio lot caused an endless tizzy. As legend has it, F. Scott Fitzgerald (while slumming in Hollywood for a paycheck, Barton Fink style), supposedly showed up at the studio commissary hung over one day, when he spotted Freaks‘ Siamese twin sisters and promptly vomited.

Once the film was complete, the true disaster set in. After an initial test screening, the audience was so violently disgusted by the film that one pregnant women threatened to sue MGM for purportedly causing her to miscarriage. The studio tried to make the film less offensive, cutting it down from 90 minutes to a threadbare 64 minutes (this cut footage is sadly all lost), but even with all the juicy moments gone, the real problem still remained: the actual freaks. There was simply no way to remove them. Freaks was box office poison at its most potent. Most audiences were never even given a chance to be disgusted by the film. Theaters simply wouldn’t show it. The film was banned in the UK for thirty years.

Browning was done. He couldn’t get shit greenlit, and this was back in the pre-television days when the studios were pumping out a heroic number of films each year. Creatively caving in, Browning attempted to resurrect his career with what seemed like an easy hit – a remake of one of his biggest Lon Chaney hits, London After Midnight (one of the more notable “lost films” of early Hollywood). But without Chaney the movie had no hook. In the original film, Chaney had played dual roles. Now the parts where split up and played by Lionel Barrymore and Béla Lugosi (whose own career was already slowly dying). Retitled Mark of the Vampire, the film did not re-ignite Browning’s career. After that Browning made only two more films, The Devil-Doll (1936) and Miracles for Sale (1939). Then he slipped into seclusion, living off his ample savings. So reclusive did Browning become that most people were unaware he was still living when he passed away in 1962 at the impressive age of 82.

Bullet Dodged, or Greatness Robbed:

Browning’s legend as a filmmaker has really gone in the shitter over the years, largely due to his most enduring hit, Dracula, which is simply not a great film. Most people consider the Spanish-language version, shot concurrently with Browning’s film on the same sets with a different cast, to be superior. Browning would have agreed. He didn’t think the film was that great either. It is probably every filmmaker’s worst nightmare to be best remembered for a film they don’t think is good.

Browning’s legend as a filmmaker has really gone in the shitter over the years, largely due to his most enduring hit, Dracula, which is simply not a great film. Most people consider the Spanish-language version, shot concurrently with Browning’s film on the same sets with a different cast, to be superior. Browning would have agreed. He didn’t think the film was that great either. It is probably every filmmaker’s worst nightmare to be best remembered for a film they don’t think is good.

Browning was certainly no Murnau or Griffith. He wasn’t a stylistic master or boundary-pusher of the cinematic form. He was a journeyman director. But he had a way about him, a stark style and objectively ruthless approach to content that while not necessarily ahead of its time, was uncharacteristic of the theatrical flamboyance of the period. Ironically, these traits frankly made him a poor choice for Dracula, as Universal wanted it.

But examining Freaks, if nothing else, gives hints at a cracked brilliance waiting to be set free. The film is mostly remembered because of its cast, but as a film itself it is quite effective. Cinema had never seen a scene like the notorious “Gooble gobble, gooble gobble! One of us, one of us!” dinner scene, which straddles the lines between horror and comedy with a dead-center perch that really wasn’t seen again until The Texas Chainsaw Massacre offered its own twisted family dinner. And you can’t watch the film’s rain-drenched climax without being impressed by Browning’s creepy staging abilities.

His second-to-last film, The Devil-Doll shows that Browning was a man drawn to fucking weird ideas. If Browning had kept going, there surely would have been at least one or two more genre minor classics up his sleeve.

Verdict: Greatness Robbed.

The Alternate Universe:

MGM embraces Freaks‘ controversial image, bragging about the dangers of watching the film: “You will never be the same!” “It just may drive you mad!” MGM puts Browning on a nationwide tour with the film, allowing him to channel the experience he gained from years in the circus. He warns audiences to watch the film at their own peril, and introduces them to the actors dressed at mental hospital employees, ready to drag them away after what they’ve seen. Browning becomes William Castle decades before Castle perfected the art of the promotional stunt. Freaks becomes a grassroots hit, and Browning is launched as the visionary behind it. Browning producers a few more hits before nearly imploding his career once more with another envelope-pushing banned film. After taking a few years off, Browning is given another chance and is paired with Lon Chaney Jr (himself experiencing major career fall-out) in a gimmick meant to evoke Browning’s partnership with Chaney Sr. Together the two produce a series of minor classics to rival Vincent Price’s output with American International Pictures.

MGM embraces Freaks‘ controversial image, bragging about the dangers of watching the film: “You will never be the same!” “It just may drive you mad!” MGM puts Browning on a nationwide tour with the film, allowing him to channel the experience he gained from years in the circus. He warns audiences to watch the film at their own peril, and introduces them to the actors dressed at mental hospital employees, ready to drag them away after what they’ve seen. Browning becomes William Castle decades before Castle perfected the art of the promotional stunt. Freaks becomes a grassroots hit, and Browning is launched as the visionary behind it. Browning producers a few more hits before nearly imploding his career once more with another envelope-pushing banned film. After taking a few years off, Browning is given another chance and is paired with Lon Chaney Jr (himself experiencing major career fall-out) in a gimmick meant to evoke Browning’s partnership with Chaney Sr. Together the two produce a series of minor classics to rival Vincent Price’s output with American International Pictures.

Remains:

Browning sadly did not live to see the second life Freaks has taken on. Like a lot of banned, shunned, and ignored art and entertainment from the first half of the 20th-century, Freaks was rediscovered by the counter-culture movement in the 1960’s and quickly became a midnight movie mainstay in the 1970’s. Now its cultural relevance has sunk deep, well beyond the reach of the film itself, from music (The Ramones), to references in things as diverse as South Park to Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers. Browning would surely have been surprised to see the film that butt-fucked his career selected for preservation by the United States National Film Registry in 1994.

Leonardo DiCaprio has long been involved with some interesting run-off from the film, as he has been trying to get a biopic based on the life of Freaks‘ Half Boy (Johnny Eck) made for years.

.

DISCUSS THIS on the CHUD Message Board

&

Like / Share it on Facebook (above or below) if you think it’s great!