The idea behind Reel Paradise is so simple that it’s great: Indie guru John Pierson (you may know him as the guy who pretty much discovered Spike Lee, Kevin Smith and Richard Linklater) takes his family to Fiji where there is the most remote movie theater in the world, the 180 Meridian Theater, right on the international date line. John and his family will spend one year on one of the smaller Fijian islands, Taveuni, showing free movies nightly to the locals. The films range from Juwanna Man to Apocalypse Now Redux.

The idea behind Reel Paradise is so simple that it’s great: Indie guru John Pierson (you may know him as the guy who pretty much discovered Spike Lee, Kevin Smith and Richard Linklater) takes his family to Fiji where there is the most remote movie theater in the world, the 180 Meridian Theater, right on the international date line. John and his family will spend one year on one of the smaller Fijian islands, Taveuni, showing free movies nightly to the locals. The films range from Juwanna Man to Apocalypse Now Redux.

Joining John is his wife Janet, and their children – 16 year old Georgia and 13 year old Wyatt. Filmmaker Steve James – the director of the classic documentary Hoop Dreams – came out for the last month of their year to document them.

It’s sort of incredible. The family dynamics are priceless. There’s household drama as they get robbed. And most of all it’s incredible to see the Fijians respond with unfettered roars when a movie really connects with them.

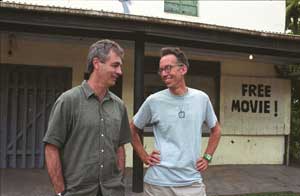

The Piersons and Steve James came to New York last week to do a press day, and I had the pleasure of meeting and interviewing them. Steve James is first, with what I think is a fascinating talk about not only this film but about documentary films in general. Look for John Pierson, who gave me a truly great interview, later on this week.

Reel Paradise opens in New York today, August 17th. It’ll be playing at the new IFC Film Center at Waverly Place. It opens September 2nd in Los Angeles and San Francisco. It’s a really funny and fun film, especially for movie lovers.

Q: I’ve heard this described as The Osbournes go on Survivor. What is the difference between a reality TV show and a documentary? Is it in the intention? The execution?

James: This film sort of has a reality TV premise in that what John and Janet did could have come out of a reality TV show. ‘Hey, we’re going to uproot our family, go and live in Fiji and run a movie theater and see what happens!’

They did it for a lot of reasons, and a lot of personal reasons. They didn’t do it because it was going to be a reality show. It wasn’t calculated in the way that reality television is. So besides the reasons that they did it, which were genuine, and which immediately takes it out of the reality television boat, the other thing that’s very different is that in reality television they would never just do that. They would manufacture all kinds of artificial obstacles and drama along the way. The Piersons didn’t do that along the way and we didn’t do that filming the last month in Fiji.

Q: You didn’t really need to. They brought enough obstacles and drama.

James: Right! Reality television has no faith in the interest of human behaviour. They believe that people aren’t going to be interested unless they can fan the flames and make it interesting. They really don’t believe that audiences find these people interesting.

James: Right! Reality television has no faith in the interest of human behaviour. They believe that people aren’t going to be interested unless they can fan the flames and make it interesting. They really don’t believe that audiences find these people interesting.

The truth is that I don’t find most of those people interesting in part because the reason people go on reality television shows is to be famous. That’s their motivation. I don’t find those people interesting. I find people interesting when they have no desire to be famous.

Q: For the last year or two when I interview a documentarian why they think documentaries are more popular now. Then my entire faith was shattered with Murderball, which didn’t do so well and which I really thought was going to just go over the top. Do you think that’s a symptom of the documentary trend ending?

James: I don’t know. I saw Murderball at Sundance, and like you I thought this was going to be a big hit for a documentary. Why didn’t it do well? I don’t know for a fact, I haven’t made a study of this, but it could be that to many people the idea of seeing people in wheelchairs is just not appealing enough for them no matter what they read about the movie. In general sports documentaries haven’t done well as a whole and this film was certainly written about as much as a sports film as anything else.

Q: Your sports film did pretty well.

James: Yes, but that defied convention too. When Hoop Dreams came out that had four or five strikes against it in terms of people’s conventional expectations. There are always exceptions.

I don’t know why – if it came out at the wrong time or in a crowded marketplace or who knows the reasons. But I don’t think we should read too much into Murderball. There are always going to be films that surprise us in terms of both how well they do and how poorly they do. Ballroom dancing did well. I haven’t seen that film, but the reviews of that film, while positive, were nowhere near as positive on a whole as Murderball.

Q: Coming from the time you did Hoop Dreams to now, is there a huge difference in the documentary world? And what is different?

James: There are a lot of things different. Audiences around the time of Hoop Dreams and prior – I don’t think Hoop Dreams was all responsible for this but was one of the films that helped this, along with Roger & Me and Crumb to some degree and others – there was a feeling that documentaries were good for you and that serious people went to see them and that they held no real interest to people as entertainment. Even though there had been, if you go back and look over the years, a number of very entertaining documentaries made, I think for the most part that was kind of true. Films had been powerful and affecting but they tended to be pretty earnest and straightforward and they weren’t trying hard to entertain. They were trying to move and inform. Which was lofty.

I think what happened is that certain films came along, and Hoop Dreams was one of those films, where word came around that this was a film that wasn’t just good for you – yeah, it’s got a lot to say – but it’s exciting and interesting. You get caught up in it. That happened for a number of films that came down the pike. There was a change in the culture a little bit in how they viewed documentaries. Then Michael Moore came along and blew the doors off with Bowling for Columbine. And truly blew the doors off with his next film.

Within the world of documentary there has developed a culture of, there’s no reason why our films shouldn’t entertain. That’s not a bad word. At one time it might almost have been a bad word in a way, you’re making light of something and it’s not serious enough. We couldn’t get funding for Hoop Dreams for years because they didn’t think it was a serious enough subject to be doing a documentary about, if you  can believe that now.

can believe that now.

I think that more and more documentary filmmakers have come along and feel an obligation that their films entertain and not just inform.

Q: One thing I wonder about is whether documentaries won’t go the way of television news, where once upon a time it was serious and solid and now it’s all tabloid sensationalist nonsense.

James: I worry about that. I worry that with distributors rushing in to embrace documentary as a commercial enterprise the impact will be that some of the more old school documentary style of filmmaking will fade away.

It’s interesting – you make the analogy to news, but I make the analogy to indie narrative film. There was a period of time when indie narrative film lived in a certain kind of ghetto and was interesting, but then it broke through and people discovered it and were like, ‘Wow, it’s incredible what we’ve been missing all these years.’ Recent years haven’t been as kind to indie narrative film as people try to find the right formula in the same way that Hollywood is always trying to find the right formula. Words like edgy – which is one of my least favorite words. Something can be edgy and stupid. There’s a lot of that out there. I have some of the same concerns in documentary.

I want there to be room for all of it. I love a good entertaining documentary as much as the next person, but I also love it when I see a film that’s deeply penetrating and not about that.

Q: Georgia said that she hated the movie. What’s your response to that?

James: I understand how she feels. I of course feel differently. And I don’t hate her in the movie, and I know a lot of people who find her a pretty fascinating subject in this film. I think she looks at this film and she sees the quote unquote bad behaviour, which I view more as the teenage rebellious behaviour. I think it makes her squirm. It makes her feel that she’s sorry she let it be filmed. The other thing she feels is that I somehow put it together in a way to make her look worse. Which I don’t think I did.

I guess what I’m saying is that I understand that coming from who she is and where she’s at, that’s her, up down and on the screen. It’s tough being the subject of a film as candid as this. I don’t begrudge her her feelings for that.

When I look at Georgia in the movie I see a rebellious teenager who is sort of typically rebellious. I see a teenager who was uprooted and taken to a foreign culture. That put some strains on her relationships with her parents and the authority figures in Fiji. But I also see a girl who, out of the four of them, was the most at home and comfortable in that culture. I certainly endeavoured to put that in the movie – the level of comfort she had in Fiji and the friendship she had with Miriama. That’s what I see and that’s what I found fascinating with her when I was there – that on the one hand she could be so at odds with John and Janet over things and on the other hand she could be totally at ease and at home in the culture.

Q: What was endearing about her to me is that she was both sides of the American abroad experience. She was on one hand the rude and obnoxious American, but she was also the American you hear about where people are amazed at how friendly and open they are.

James: Absolutely. In fact one of the things I felt when we were making the film, and I was trying to get across without the hammer to the head, is that the Piersons as a whole represent Americans in the world. John the proselytizer. John who has got something he wants to get across to the souls of the people of Taveuni – it was a joke, but it was also true. Janet the peacekeeper. The get along and do what you can to keep everybody happy. Wyatt was sort of the ideal, model student. But also Wyatt has that biting, sarcastic quality Americans are known for. And then Georgia like you say.

Q: Do you often get subjects coming back and hating how they appear?

James: I would say that Georgia has been the most vocal in that regard. In Stevie, Stevie’s mother Bernice was not happy with the film. I could never get her to talk to me about it in any substantial way, but she would say things like ‘I’m sorry I ever agreed to be in that.’

What I find interesting is that sometimes subjects – outside of Bernice and Georgia, I don’t know that I’ve had any other main subjects who were really unhappy with their portrayal. Which is not to say they’re completely happy. What I find interesting is that people sometimes who – and this was true with Bernice and I know this will be true with Georgia – there are people who are going to be critical of some of the things they see, we’ll see that in print, we’ve seen it in print at festivals. What we’ve also seen is people who kind of get it. I’ve found that the people who are the most judgmental about these things, about Georgia in this movie, are the people who either don’t have kids or have somehow lost touch with who they were as teenagers.

What I find interesting is that sometimes subjects – outside of Bernice and Georgia, I don’t know that I’ve had any other main subjects who were really unhappy with their portrayal. Which is not to say they’re completely happy. What I find interesting is that people sometimes who – and this was true with Bernice and I know this will be true with Georgia – there are people who are going to be critical of some of the things they see, we’ll see that in print, we’ve seen it in print at festivals. What we’ve also seen is people who kind of get it. I’ve found that the people who are the most judgmental about these things, about Georgia in this movie, are the people who either don’t have kids or have somehow lost touch with who they were as teenagers.

I feel my duty as a filmmaker is to do my best to try and present people in a complex, three-dimensional way and to be true to what I saw. It’s what I saw, it’s my truth. But at the same time to do what I can to discourage the viewer from easy judgments.

Q: You spent the last month on Fiji with the family. Do you think it would have been a very different picture if you had spent more time with them, or had been there the whole year?

James: Absolutely. I think that’s an important point. This is much more of a snapshot. The snapshot that this film is was their last month in Fiji. That was a month when Georgia was in a more rebellious state than she was in the other 11 months. The house got robbed. There was more tension. I think it adds an interesting dramatic element to the movie, but in terms of their own feelings about their experience and all that, it was colored by that robbery, because it was the second robbery they had been through.

So yes, its’ more of a snapshot. If we had been there for the entire duration we would have seen Georgia in Suva [the capitol of the Fiji Islands], and spent more time with her in Suva, where she lived by herself. We would have witnessed the growing closeness between Wyatt and Georgia I had been told about. I saw it, but it happened in Fiji. When they got there they didn’t really hang out much but they got closer. We would have seen some of those kinds of things.

On the other hand if we had been there the entire time, it could have ruined their experience of Fiji. If they had shown up with a camera crew – what that would have communicated to the people of Fiji was that they were there for a movie. ‘You’re not here to run a movie theater and show us free movie – you’re here to make a movie.’

There was good and bad by being there for the last month.

Q: This film almost – and hear me out, since this is going to sound horrible when I begin the sentence. This film is almost about the triumph of the stupid. I’ve seen 75 movies this year, and I’m about as burned out on movies as I could have imagined myself ever being, but watching this reminds you of what it’s like to be in a crowded theater and just having a great fucking time watching a movie. And its’ the stupidest ones that work best, that they like. Did John walk into this knowing that it would be the triumph of the stupid movie?

James: I don’t know. That would be a good question for him. He didn’t go in there, as he says in the movie, thinking The Girl With the Pearl Earring would go over. He did, on his first – not in the movie, but in the very first Split Screen episode where they discovered the theater – they showed this movie by Don Ward called The Suburbans, which I never saw but it was more of an entertaining film, I guess. They also showed American Movie, which is a very entertaining documentary. John figured if he was going to show a documentary it would have to be something funny and entertaining, so he picked American Movie, which is hilarious. It did not go over at all.

Q: I would assume they have no context for it.

James: They couldn’t relate at all. He made a discovery that informed everything he did subsequently that informed everything he did with the movies. He did bring in things like Rabbit Proof Fence and he did bring in Bend it Like Beckham, some of these films that are not stupid but that he felt they could relate in some way to. He showed Buster Keaton. He showed smart movies over the time he was there and people got them, but he had to be careful how he selected those movies because he always knew that films like The Hot Chick would always play well.

informed everything he did with the movies. He did bring in things like Rabbit Proof Fence and he did bring in Bend it Like Beckham, some of these films that are not stupid but that he felt they could relate in some way to. He showed Buster Keaton. He showed smart movies over the time he was there and people got them, but he had to be careful how he selected those movies because he always knew that films like The Hot Chick would always play well.

When I first met John in connection with Hoop Dreams coming out I had the perception of him, which I think a lot of people do if they know his background, where I assumed he must only like the rarified indie films. That he probably has no interest in Hollywood movies. Nothing could be further from the truth. Once I got to know John, he’d say, ‘Hey did you see Batman yet?’ He sees everything. He loves everything. He loves movies. Which doesn’t prevent him from getting what’s great about the best indie movies, but it also doesn’t keep him from enjoying stupid humor.

I saw a movie in LA, a bad movie – How Stella Got Her Groove Back – I saw it at the Magic Johnson Theater. It was a great experience. The movie sucked. But it was a great moviegoing experience because the audience was talking back to the characters. The movie wasn’t nearly as funny as the retorts from the audience to the woman. I think there is something to be said for that communal aspect of watching movies. As DVDs become triumphant and we all begin watching movies by ourselves in our own houses, as we do everything else these days, that will be something that is lost.

The other thing that is in the movie that I really like – and it’s not a big deal, but I think it’s revealing – is that movies like Bringing Down the House, which I think is a fairly marginal film at best, in Fiji what they find so intoxicating is not just the stupid pratfalls. It’s the notion that here’s this black woman taking over this white man’s house. They have a white community in Fiji, and they tend to be like everywhere else richer and better off. So to the Fijians this is shocking. It would never happen so of course it’s a perfect comic premise. It worked on a level for them that was supposed to work here, but it can’t work to that degree. It’s not done very well and we’re too sophisticated.

Q: Was there a problem getting the clearances for all the film clips?

James: It is a struggle. One of the big issues in the documentary filmmaking community right now is property rights – what you can show and what you have to pay for. It wasn’t too long ago making this film that we would have proceeded from the premise that we’re making a documentary about a guy who shows films so we have to show the films. We don’t pay for this – it’s a documentary! Documentaries were considered to fall, for a long time, under the umbrella of journalism. ABC news, if they did a story on one of my films and excerpted it, they wouldn’t call up and ask if the could use it. They use what they want – they’re news. Documentaries stopped falling under that umbrella in part because they’re perceived as entertainment. Now you have to license everything.

It was a struggle because we’re a small little film with very little money. We had to fight tooth and nail in some cases to get them to let us use it and then to get them to give it to us cheap. Because it ain’t cheap. Then you also have to license the music.

Q: Separately?

James: And not just if someone is singing, like Chicago. You have to license the score. Then you also now have to get releases signed by every actor in the scenes. We had to get releases signed by all these huge stars. We had to get Renee Zellwegger and Queen Latifah and Steve Martin and Halle Berry. That was a chore because we weren’t calling them up and saying we want to pay your client 20,000 dollars. We were calling them up and saying we’d like them to sign this release and all we can pay is the SAG minimum, which we had to pay, which is like 400 dollars. It was hard to get the agents for Steve Martin to even want to mess with it.

Q: Was there anyone who turned you down?

James: Matrix, they made it clear from the get go that they wouldn’t license it. John predicted that and we didn’t even go after it. The film Jackass, at first they turned us down. In part because there had been when that movie came out an Oprah show about people copycatting Jackass stunts, and there had been an urban legend – and it’s important to understand that it is an urban legend – that a guy had died doing a Jackass stunt. They just wanted Jackass to go away – not financially, but they said their policy was not to license that movie. When we pursued it they told us why. In our film we have a whole thing about whether it’s having an impact [on the Fijians]. We had to enlist the support of Spike Jonze, we had to enlist the support of the president of MTV productions. We got great support from Paramount to break out of this mindset, and we got to use it. To their credit we only had to trim one line out of the whole Wyatt/Janet debate. Spike Jonze saw the sequence and said he loved it. We made this argument to Paramount that the debate is great because Wyatt is making a strong case that they won’t imitate any of it.

Q: Does the year of free movies do anything for the islanders?

James: I think that Gopal, the Fijian you hear commenting at the end, hits the nail on the head. People will always remember that this happened. It will be a memory of a lifetime. Some of the old Fijians, like Gopal, remember going to the movies as kids because the economic situation, marginal as it might have been then, was better. Movies were cheaper. They were able to go to movies. He had tons of fond memories of seeing movies, of seeing The Godfather at the theater when he was a kid. Some of the older Fijian remembered with fondness going to the movies but they hadn’t been able to do it again until John arrived because even a dollar Fijian was unaffordable. If someone came along and did a film 20 years from now, the people who are kids now will remember when there were free movies and the tall white guy and his  family were there.

family were there.

Q: Are there any plans to show this film in Fiji?

James: There would be some problems with showing this film in Fiji. We would have to make some changes, like the part about Miriama’s father and mother, where we learn her father was physically violent to her mother, we would take that out. Not because it’s untrue but because that would be very embarrassing her to a way that’s different from here in the sense that we’re much more jaded about those things.

I think that, as Wyatt would tell you, this would not go over well in Fiji. In that village they would have fun seeing people they knew. They wouldn’t relate to it how you related to it.