There are moments, big and small, throughout the history of cinema that make up our collective pop culture. While some are recognizable even to the most casual filmgoer, this column will be focusing on the lesser discussed moments, moments that you might not have considered before. Without them, the film wouldn’t be the same, even if you haven’t noticed it until now, and they matter just as much.

The Movie: The Bridge on the River Kwai

The Gist: After being captured by Japanese forces and sent to a POW camp in WWII, a British lieutenant colonel enters into a battle of wills with the prison’s colonel about how they expect to be treated, and how they will be put to work. After finding a small amount of middle ground, he and his men avoid the crippling monotony of prison life by focusing their efforts on building the best damn bridge anyone’s ever seen–except the bridge is meant for their enemy. Pondering about what kind of personal satisfaction a man can find even when forced to work for his enemy occurs. Greatness happens all over the place.

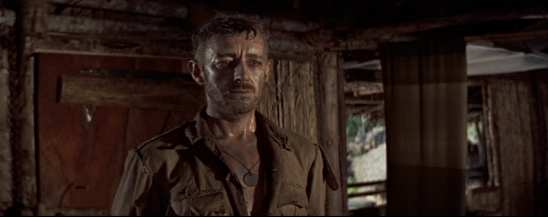

The Moment: After a weeks-long standoff between Lt. Col. Nicholson (Alec Guinness, in the real role that should come to mind when you hear his name) and Col. Saito (Sessue Hayakawa) about the treatment of POWs and the division of labor, a reckoning is finally had, though it is at first presented as simple resolution to a disagreement. Nicholson contends that under the Geneva Convention, commissioned officers are to oversee any manual labor POW soldiers might be ordered to do, and as such cannot be forced into manual labor themselves; Saito does not care for anything resembling British code or chain of command, stating that they are all the same to him. But Saito has been ordered to use the POWs to build a crucial bridge to move supplies over the river Kwai (hey, a title!), and with his deadline looming and his personal honor at stake, Saito calls Nicholson into his office, telling him that in celebration of the Japanese victory over Russia in 1914, and in the interest of new beginnings, he will release Nicholson and his officers from being required to participate in the labor, and will in fact be an equal voice in the construction project. Nicholson, knowing he’s won the argument, salutes and exits the office. As the cheers from Nicholson’s men fill the office, Saito, thus far shown to be a strong willed and fearsome opponent, weeps harshly and deeply, knowing that even though he might have saved face publicly, he will never forgive himself for caving. His personal honor, in this moment, has been lost.

Why it Matters: It’s a hell of a thing, making an audience care about someone who would traditionally fill the “bad guy” role, and while as the film goes on you learn more about Saito and even eventually earn a begrudging respect of the man and his commitment, this moment sets up all those later revelations in character by showing this man at the most vulnerable and defeated point in probably his life. This man, who from the first frame exudes strength, unrelenting motivation, and a dominating command of his men and his prisoners, is shown cowering in a corner, weeping tears that even he probably didn’t know he was capable of. Not only does this put a very human shading on what could have easily been a mustache twirling type of foil at a time where you were lucky if the actor playing the part was even Asian, let alone Japanese, it gives any feeling person watching the last thing they might have expected when they sat down: empathy.

Empathy for your enemy’s cause is a tricky thing to achieve, especially in a war film. So often war films end up marginalizing the human aspects of the antagonists, or remove the actual character from the film to the point where it’s mostly just faceless canon fodder for the heroes to mow through. Saito, however, is shown to be every bit as determined and as intelligent as Nicholson, and the two even end up with a begruding respect for each other, which starts to border on actual mutual appreciation by the end. For the audience to buy this, though, without turning on Nicholson as well (though his tunnel vision focus on completing the bridge might intentionally make you question the man), the audience first has to invest in Saito as a human being.

His plight is made clear: he has superiors that he wishes to impress, and one gets the feeling that even though he’s a driven, competent, and keen-minded officer, he feels unappreciated or at the least marginalized by his superiors, and it’s hinted that his subordinates don’t think much of him either. The man has discipline and drive, but the world seems not to care or notice. This bridge, for him, isn’t just an assignment, it’s a chance to prove his worth to the high command as well as to his men. He’s running the show, and by God, he’s going to run it his way, get it done on schedule, and no one will stand in his way. If he fails, his shame will be so public and resounding that he will have no choice but to commit seppeku.

Then this Nicholson comes in and screws it up for him. A classic case of an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object, at first Saito tries to force Nicholson and his men into submission, but when it becomes clear that that won’t work, he tries bribing, but in such a way that Saito’s authority would still be unquestionable (and possibly appeal to some heretofore unseen selfish side of Nicholson). Finally, we come to this moment when Saito must chose which he values more: his personal honor, or the success of the bridge. He won’t bend Nicholson, can’t bend Nicholson; Nicholson’s a force of nature, his British pride and resolve proven unshakable and unbreakable.

So he forces himself to come up with a bullshit loophole so Nicholson will get his men working properly while not outwardly appearing to have lost his total authority over his prisoners. He explains the situation to Nicholson in a flippant, almost uninterested manner, as though he were telling Nicholson that it’s hot outside and that they’re in Japan. Saito attempts to make the matter appear trivial, meaningless, but Nicholson knows better. He knows he’s won. Doesn’t gloat or snark; such behavior is unbecoming of a British officer. Just buttons his shirt, says “Thank you,” does an about face and leaves the hut. He won’t be caught dead reveling in the situation.

His men instead do the celebrating for him, loudly and indiscriminately. They cheer, they whoop, they holler, they make this victory known throughout the camp. For them and for us, the viewer, this is a triumphant scene, where the resolve of the Allies has gone toe-to-toe with the determination of the Japanese, and come out on top. But then we cut to Saito weeping, and we are reminded that even though we know the sweet taste of victory, we also recognize the bitterness of complete and total abject humiliation, and one cannot help but suddenly see a little of themselves in this man previously regulated solely to the adversary department. It’s a hell of a thing, seeing a strong man cry, not because of a tragic loss due to an outside force, but the equally devastating loss of your self respect because you weren’t strong enough or smart enough to do what was expected of you.