Talking to Marti Noxon – as I did about I Am Number Four – certain things have come into more focus about the state of cinema. As a film lover, we’re at a point now where the studio system is less likely to take chances on character-driven material like television will. And we’ve also seen a class of comedies (Arrested Development, Community, Cougar Town, Parks and Rec) and dramas (Justified, Mad Men, The Shield, The Wire) that have season-long and show-long arcs that are on par with anything the big-screen produces. It should be a different storytelling art, but the shorthand of yesteryear – the economy that can only comes from visual storytelling – is not a priority in the studio system. With many television writers (and television developed out of radio) working for the big screen, you’re seeing the influence of a more aural medium. When was the last time you were in a theater and had a moment like the chill and realization that came from William H. Macy seeing a body, and then the pan over to his trunk popping like in Fargo? That’s a shot that tells a story without dialogue, something you rarely get from the modern B movie.

Talking to Marti Noxon – as I did about I Am Number Four – certain things have come into more focus about the state of cinema. As a film lover, we’re at a point now where the studio system is less likely to take chances on character-driven material like television will. And we’ve also seen a class of comedies (Arrested Development, Community, Cougar Town, Parks and Rec) and dramas (Justified, Mad Men, The Shield, The Wire) that have season-long and show-long arcs that are on par with anything the big-screen produces. It should be a different storytelling art, but the shorthand of yesteryear – the economy that can only comes from visual storytelling – is not a priority in the studio system. With many television writers (and television developed out of radio) working for the big screen, you’re seeing the influence of a more aural medium. When was the last time you were in a theater and had a moment like the chill and realization that came from William H. Macy seeing a body, and then the pan over to his trunk popping like in Fargo? That’s a shot that tells a story without dialogue, something you rarely get from the modern B movie.

I have gotten into fights for calling Star Trek – the entertaining ’09 reboot – a pilot, but as a narrative that’s all it is. It’s about getting characters in place for their next adventure, giving you the broad outline of their characters until they settle into the roles that were made famous by other actors. I’ve never seen someone successfully argue that there are themes at work there that aren’t “destiny” as cribbed loosely from Lucas. Regardless, it works, and J. J. Abrams has developed enough flair to make it a good-enough popcorn ride, but these sorts of films that don’t have anything going on under the surface – while also not being a complete narrative unto themselves – are growing tiresome (Robin Hood, The A-Team, The Losers, and on and on). It seems if a studio spends a certain amount of money on a title they want to make sure it can be franchised, and it’s leaving me with blue balls. Arguably, romantic comedies break this trend, but those films are usually about making a brand of their stars (Kate Hudson, Katherine Heigl), so they can do more of the same.

The cart is now so in front of the horse that films rarely feel like a meal as much as an advertisement for future adventures, unless the film has some form of Oscar aspirations. It’s also why Inception was such a breath of fresh air. This serialized nature is slightly more palatable in comic books, as it reflects their origins, but those tend to – at least – have a big baddie who is soundly defeated at the end. It’s no less formulaic, but it tends to give a great sense of closure to the narrative. The other problem is that the grammar of the cinema of these films is often similar to television, just done on a grander scale – it’s coverage-based. You have more types than characters – you don’t have the time to grow to love the characters who are sketchily defined – there’s the people you theoretically care about, but whatever empathy you have generally comes because of the performers involved (and the performers being good looking), but generally there’s no sense of a finished journey. If you did, then you couldn’t have sequels. Now there are more endings where it’s not just that there could be sequels, but a sense there has to be a sequel. As a filmgoer, you’re getting fucked. With the Lord of the Rings it was understood, with The Losers, it’s a spit in the eye.

So much of cinema comes directly from television these days. It used to be that it was just music video and commercial directors – and it still is to some extent (David Fincher, Mark Romanek, Joseph Kahn Spike Jonze, etc.) – but now more than ever we’re seeing the talents behind TV go back and forth from big screen to small. This goes both ways (as I’ve noted in the past) with people like Frank Darabont and Todd Haynes, but also last year saw Eat, Pray Love directed by the creator of Glee. DreamWorks executive Steven Spielberg began his career in television, and some of the best directors going these days (from Michael Mann to Edgar Wright) cut their teeth on television so it’s not necessarily a cross to bear, but you also get directors like Mimi Leder, Clark Johnson, and D.J. Caruso.

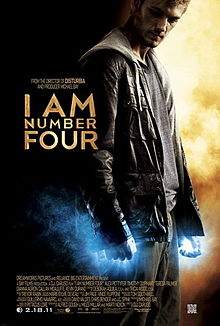

These are filmmaker without much personal style or perceptible storytelling interests. Not every director is an auteur – nor should directors be harshly judged for simply delivering something that’s just entertaining (entertaining is hard enough) – but Caruso and his ilk seem to do what they’re told. And when you partner him with three writers who have specialized in television, and with the open-ended storytelling that comes from adapting a series of books, you get a non-film like I Am Number Four. It’s not terrible, but it feels more like a pilot than a movie. In some ways it makes you long for the cinematic thinking of someone like Christopher Columbus. How sad is that?

In I Am Number Four Alex Pettyfer stars as John Smith, an alien who is the number four of the title. He has a guardian Henri (Timothy Olyphant), and any time he does anything remotely alien, they leave town and destroy all evidence of their past behind them. They are called Loriens (from the planet Loreal?) and are being hunted by the Mogodorians, who killed off the rest of their race, excepting the (nine?) remaining children who can supposedly stop the bad guys from completing their genocide through their magical, mystical, undefined powers. This though is awkward because we don’t really know how many there are (there are at least six in total, as Teresa Palmer plays number six – the interviews I did told me there were nine), or why they have to be killed in order. This chase is the inciting incident of the story, which sets up some of the film’s problems (there’s no sense of the rules of the universe), but that isn’t so problematic in the scheme of things, or at least wouldn’t be if the film was more compelling. The film opens with Number Three dying in a sequence that is shot exceptionally dark and muddled, and the death of three makes John’s leg light up like a firework. This is also happening as it looks like he might score with a woman, so it seems to connect his alien outbursts with his sexuality, though it’ s never a plot point (so much as his emotions sometimes make him use his powers, so it’s got that Spider-Man thing). This forces him to move from Florida to Paradise, Ohio, where he plans on going to school against Olyphant’s objections. Already you’ve got a little superhero, a little Potter, and a little Twilight, which likely has everything to do with its source – a young adult novel, and most of those have been modeled on what’s successful of late.

At school John meets the bullied Sam (Callan McAuliffe), and hottie Sarah (Dianna Argon), the cute girl who doesn’t quite fit in after she left her boyfriend – and cock of the walk – Mark (Jake Abel). Mark and his friends pick on Sam and John gets in the middle, showing himself proficient physically, while also coming to realize his otherworldly powers. Sam unintentionally puts himself in the middle of an ongoing feud between Sarah and Mark, which must eventually escalate to violence. John’s supposed to be invisible, which is hard when Sarah likes taking pictures that Henri must erase from her website. Henri wants constant updates on his location, and threatens to revoke some of John’s privileges if he doesn’t comply, but John never seems to comply, so that threat never amounts to much.

The film hits what can be called its groove when Sarah and John start to date. Yes, their love is modeled partly on Twilight (John’s alien race mate for life), but the two have a believable chemistry and neither is exactly hard on the eyes. This will – of course – be interrupted by the evil Mogodorians (headed by Kevin Durand in a fun, aware performance) who are eventually going to catch up with him, because they’re good at stalking and have one goal. But then also Number Six (Palmer) – a total bad ass – is looking to help Four, and she’s learned in the arts of Badassery.

The love story is what makes the movie palatable, and it’s the core of the film, so that helps keep this film slightly above terrible, though again, it’s toeing its foot in the franchise pool. There’s such small-minded thinking going on across the board. The actors wouldn’t be out of place on network shows (nothing against Argon and Olyphant, who are TV stars), and when the film finally unleashes the big end fight sequence, it’s slightly larger than most things put on the small screen -perhaps because the source material isn’t all that great (though I can’t be sure because I haven’t read it). Sadly, Olyphant – as much of a TV actor as he is, and as much as both Deadwood and Justified make him look like a movie star – has nothing to do here but be concerned. I loved what Olyphant did with his supporting character in The Girl Next Door, this has none of those dimensions. While Teresa Palmer’s character hits exactly one note. Palmer looks good doing it, but that’s all there is. And dimension is exactly what this film is lacking. As a February release, I’m sure everyone involved knows this isn’t a masterpiece, but worse than it not being a great movie, it doesn’t feel much like a film, period. I’m not the sort to pull a Dirty Harry and throw my badge to the ground, but the more cinema we get like this, the harder it is to defend my favorite art form. What’s on television tonight? Community? I have no doubt tonight’s episode smokes this in terms of visual storytelling, and anything else you’d want to throw at it.

Rating:

Out of a Possible 5 Stars